Everyone has heard about the miraculous stories of recovery from cancer using immunotherapy. Immunotherapy involves giving the sick person substances which stimulate the person's own immune system to battle the cancer. And when it works, it's wonderful. But...there's another side - a dark side of the harms from these treatments - that is rarely discussed, and why we should be very careful going forward.

Everyone has heard about the miraculous stories of recovery from cancer using immunotherapy. Immunotherapy involves giving the sick person substances which stimulate the person's own immune system to battle the cancer. And when it works, it's wonderful. But...there's another side - a dark side of the harms from these treatments - that is rarely discussed, and why we should be very careful going forward.

Here are two articles that do point out the problems - such as in some people the immunotherapy actually accelerates the cancer being treated (called "hyperprogression of tumors"). Studies suggest that these people share certain genetic characteristics or they are over the age of 65. In general, many patients undergoing immunotherapy have side-effects, some even developing life-threatening ones, from the treatments. Also, most patients do not respond to the immunotherapy treatments, for reasons that remain largely unknown. Obviously more studies are needed. Remember, this field is in its infancy.

Excerpts from Bob Tedeschi's article, from STAT: Cancer researchers worry immunotherapy may hasten growth of tumors in some patients

For doctors at the University of California, San Diego, it was seemingly a no-lose proposition: A 73-year-old patient’s bladder cancer was slowly progressing but he was generally stable and strong. He seemed like the ideal candidate for an immunotherapy drug, atezolizumab, or Tecentriq, that had just been approved to treat bladder cancer patients. Doctors started the patient on the drug in June. It was a spectacular failure: Within six weeks, he was removed from the drug, and he died two months later.

In a troubling phenomenon that researchers have observed in a number of cases recently, thetreatment appeared not only to fail to thwart the man’s cancer, but to unleash its full fury. It seemed to make the tumor grow faster. The patient’s case was one of a handful described last week in the journal Clinical Cancer Research. Of the 155 cases studied, eight patients who had been fairly stable before immunotherapy treatment declined rapidly, failing the therapy within two months. Six saw their tumors enter a hyperactive phase, where the tumors grew by between 53 percent and 258 percent.

“There’s some phenomenon here that seems to be true, and I think we cannot just give this therapy randomly to the patient,” the author of the study, Dr. Shumei Kato, an oncologist at UC San Diego, said in an interview with STAT. “We need to select who’s going to be on it.” .... But similar findings were published last year by cancer researchers at the Gustave Roussy Institute in France. These results were considered controversial by some, since they hadn’t been widely confirmed by other oncologists.

In the latest Clinical Cancer Research findings, those who experienced the hyperprogression of tumors, as the phenomenon is known, shared specific genetic characteristics. In all six patients with so-called amplifications in the MDM2 gene family, and two of 10 patients with alterations in the EGFR gene, the anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapies quickly failed, and the patients’ cancers progressed rapidly. ....Doctors who prescribe immunotherapies may be able to identify at-risk patients by submitting tumors for genetic testing, Kato and his coauthors suggested.

The findings published last year by the Gustave Roussy team also appeared in Clinical Cancer Research. In that study, of 131 patients, 12 patients, or 9 percent, showed hyperprogressive growth after taking anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapies. The lead author of that study, Stephane Champiat, acknowledged that the research so far raises more questions than it answers. ... Champiat suggested factors that could be associated with the effect. In his study’s patients, for instance, those who were older than 65 showed hyperprogressive growth at twice the rate of younger patients.

Oncologists studying this phenomenon said it could complicate treatment strategies, becausesome patients who receive immunotherapies can exhibit what’s known as “pseudo-progression,” in which tumor scans reveal apparent growth. In reality, however, the scans are instead showing areas where the cancer is being attacked by armies of immune cells. Roughly 10 percent of melanoma patients on immunotherapies, for instance, experience this phenomenon.

Jimmy Carter is perhaps the best-known immunotherapy success story. But most patients do not respond to the immunotherapy treatments, for reasons that remain largely unknown. In a study by Prasad and Dr. Nathan Gay, also of Oregon Health and Science University, nearly 70 percent of Americans die from forms of cancer for which there is no immunotherapy option, and for the rest who do qualify forimmunotherapy, only 26 percent actually see their tumors shrink.

And while immunotherapies typically include less intrusive side effects than chemotherapy, those side effects, when they happen, can be life-threatening. Researchers have reported cases in which immunotherapies attacked vital organs, including the colon, liver, lungs, kidney, and pancreas, with some patients experiencing acute, rapid-onset diabetes after receiving the treatments. But in those cases, the treatments were at least attacking the cancer. Such reports didn’t raise the specter of these treatments possibly working on the cancer’s behalf to shift it into overdrive.

A group of killer T cells (green and red) surrounds a cancer cell (blue, center). Credit: NIH.

A group of killer T cells (green and red) surrounds a cancer cell (blue, center). Credit: NIH.

From Health News Review: Cancer immunotherapy: more reason for concern?

Immunotherapy for cancer — which basically involves manipulating our immune system to attack cancer cells — is ever so slowly creeping toward the scrutiny phase. This slow crawl is something we reported on four months ago. With few exceptions, like this deep dive by the New York Times (the Cell Wars series ), we found many journalists completely overlooked the harms (some life-threatening) of this oft-vaunted treatment.

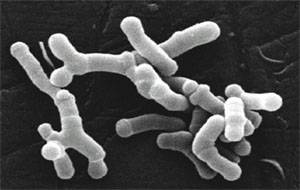

In the future, giving specific microbes or entire microbial communities may be part of some cancer treatments! This is because the composition of a person's gut microbiome (the community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses) influences whether a person responds to immunotherapy drugs. This means that the mixture and variety of microbial species living in your intestines may determine whether you respond to cancer immunotherapy drugs. Wow!

In the future, giving specific microbes or entire microbial communities may be part of some cancer treatments! This is because the composition of a person's gut microbiome (the community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses) influences whether a person responds to immunotherapy drugs. This means that the mixture and variety of microbial species living in your intestines may determine whether you respond to cancer immunotherapy drugs. Wow!

Everyone has heard about the miraculous stories of recovery from cancer using immunotherapy. Immunotherapy involves giving the sick person substances which stimulate the person's own immune system to battle the cancer. And when it works, it's wonderful. But...there's another side - a dark side of the harms from these treatments - that is rarely discussed, and why we should be very careful going forward.

Everyone has heard about the miraculous stories of recovery from cancer using immunotherapy. Immunotherapy involves giving the sick person substances which stimulate the person's own immune system to battle the cancer. And when it works, it's wonderful. But...there's another side - a dark side of the harms from these treatments - that is rarely discussed, and why we should be very careful going forward. The possibility of giving microbes in the future (whether bacteria, viruses, or fungi) to treat cancer is amazing. Of course big pharma is pursuing this line of research, which is called immunotherapy (stimulating the body's ability to fight tumors). The Bloomberg Business article discusses a number of big pharma companies entering the field and their main focus. The study in the journal Science finding that giving common beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum) to mice to slow down melanoma tumor growth is a first step. The researchers themselves said that the 2 common beneficial bacteria species exhibited anti-tumor activity in the mice and was as effective as an immunotherapy in controlling the growth of skin cancer. But note that the bacteria needed to be live. Stay tuned....

The possibility of giving microbes in the future (whether bacteria, viruses, or fungi) to treat cancer is amazing. Of course big pharma is pursuing this line of research, which is called immunotherapy (stimulating the body's ability to fight tumors). The Bloomberg Business article discusses a number of big pharma companies entering the field and their main focus. The study in the journal Science finding that giving common beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum) to mice to slow down melanoma tumor growth is a first step. The researchers themselves said that the 2 common beneficial bacteria species exhibited anti-tumor activity in the mice and was as effective as an immunotherapy in controlling the growth of skin cancer. But note that the bacteria needed to be live. Stay tuned....