Excerpts from an interesting article about microbes and some findings from 2014. From Wired:

9 Amazing and Gross Things Scientists Discovered About Microbes This Year

We can’t see them, but they are all around us. On us. In us. Our personal microbes—not to mention those in the environment around us—have us outnumbered by orders of magnitude, but scientists are only beginning to understand how they influence our health and other aspects of our lives. It’s an increasingly hot area of science, though, and this past year saw lots of interesting developments. Here are some of the highlights.

When you move, your microbes move with you

In a study published in Science in August, scientists cataloged the microbes of seven families, swabbing the hands, feet, and noses of each family member—including pets—for six weeks. They also collected samples from doorknobs, light switches, and other household surfaces. Each home had a distinct microbial community that came mostly from its human inhabitants, and the scientists could tell which home a person lived in just by matching microbial profiles. Three of the families moved during the study period, and it only took about a day for their microbes to settle in to the new place. As the journal’s editors put it: “When families moved, their microbiological ‘aura’ followed.”

Microbes could help solve crimes

Scientists made several findings this year that could potentially show up in court one day. One study found that the microbiome of human cadavers evolves in a predictable way, hinting at a new way to determine time of death. And earlier this month, researchers suggested that bacteria on pubic hair could be used to identify the perpetrators of sex crimes—especially useful when a rapist uses a condom to avoid leaving behind DNA evidence.

Your gut bacteria may be inherited

Exactly which bacteria choose to take up residence in your gut is determined, in part, by your genes, scientists reported this year after examining more than 1,000 fecal samples from 416 pairs of twins... One of the most heritable types was a family of bacteria called Christensenellaceae, which are more abundant in lean people than in obese people.

Forget fecal transplants, poo pills may be just as effective

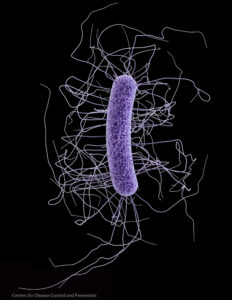

Clostridium difficile (pictured) is a nasty bacteria that wreaks havoc on the guts and kills 14,000 people a year in the US alone. Normally, other intestinal bacteria keep C. diff in check, but in the worst infections it starts to dominate. One effective but off putting treatment is a fecal transplant: taking a stool sample from a healthy person and transplanting it into the patient (in through the out door, so to speak). This year researchers developed a less cringe-inducing alternative. They created odorless frozen capsules that contained bacteria isolated from healthy stool samples. The poo pills successfully treated 18 of 20 patients with antibiotic-resistant C. diff infections, the team reported in JAMA in October.

Yeast evolved to lure fruit flies (not to make delicious beer)

There is crazy microbial diversity in cheese rinds

A tiny crumb of cheese rind contains about 10 billion microbial cells: bacteria and fungi that turn boring milk into something funky and delicious. Although cheesemakers have been manipulating them for centuries, not much is known about these microbes. This year scientists conducted the largest study yet on the microbial diversity of cheese, examining 137 cheeses from 10 countries.They found that microbial communities vary according to the style of cheese, but not so much according to where the cheese is made.

The microbiome could be a source of novel drugs

The bacteria that live on and in our bodies make countless molecules. Some of those molecules might make good drugs.

We may need new branches on the tree of life for all the microbes

Life on Earth has traditionally been divided into three domains: Eukaryotes (plants, animals, and all other organisms that stash their DNA in a special compartment—the nucleus—inside their cells), Bacteria (our familiar one-celled friends and foes), and Archaea (single-celled organisms that are biochemically and genetically distinct from the other two groups). But do we really know that’s all there is? We do not, two scientists argued last month in Science. There may be entire domains of life that have eluded our methods of detection.

Without microbes, life as we know it would end

In December, two scientists posed a thought question in the journal PLOS Biology: What would happen in a world without microbes? ...Without nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria, crops would begin to fail. Decomposition would stop, waste would pile up, and the nutrient recycling that supports life as we know it would grind to a halt. “We predict complete societal collapse only within a year or so, linked to catastrophic failure of the food supply chain,” the researchers write. “Annihilation of most humans and nonmicroscopic life on the planet would follow a prolonged period of starvation, disease, unrest, civil war, anarchy, and global biogeochemical asphyxiation.”

Clostridium difficile. Credit: CDC

Clostridium difficile. Credit: CDC