Over time researchers have learned that the appendix is more complex than originally thought, and that it is beneficial to health. It's where good bacteria go to hideout during sickness (e.g., food poisoning) or when a person is taking antibiotics, and it acts as a "training camp" for the immune system.

This is the direct opposite of what was thought for years - that it is a vestigial organ with no purpose. Instead, research found that removing the appendix increases the risk for irritable bowel syndrome and colon cancer. It also plays a role in several medical conditions, such as ulcerative colitis, colorectal cancer, Parkinson's disease, and lupus.

One possibility is that it protects against diarrhea. The appendix acts as a safe house for beneficial bacteria. We now know that it contains a thick layer of beneficial bacteria. People who've had their appendix removed have a less diverse gut microbiome, and with lesser amounts of beneficial species.

By the way, recent research found that antibiotics can successfully treat up to 70% of uncomplicated appendicitis cases. For this reason, it is recommended that antibiotics should be tried first in uncomplicated appendicitis cases. And if needed (e.g., if there are recurrences of appendicitis) surgery can be done.

Excerpts from Medscape: The 'Useless' Appendix Is More Fascinating Than We Thought

When doctors and patients consider the appendix, it's often with urgency. In cases of appendicitis, the clock could be ticking down to a life-threatening burst. Thus, despite recent research suggesting antibiotics could be an alternative therapy, appendectomy remains standard for uncomplicated appendicitis.

But what if removing the appendix could raise the risk for gastrointestinal (GI) diseases like irritable bowel syndrome and colorectal cancer?

That's what some emerging science suggests. And though the research is early and mixed, it's enough to give some health professionals pause .

"If there's no reason to remove the appendix, then it's better to have one," said Heather Smith, PhD, a comparative anatomist at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona. Preemptive removal is not supported by the evidence, she said.

To be fair, we've come a long way since 1928, when American physician Miles Breuer suggested that people with infected appendixes should be left to perish, so as to remove their inferior DNA from the gene pool (he called such people "uncivilized" and "candidates for extinction"). Darwin, while less radical, believed the appendix was at best useless — a mere vestige of our ancestors switching diets from leaves to fruits.

What we know now is that the appendix isn't just a troublesome piece of worthless flesh. Instead, it may act as a safe house for friendly gut bacteria and a training camp for the immune system. It also appears to play a role in several medical conditions, from ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer to Parkinson's disease and lupus. The roughly 300,000 Americans who undergo appendectomy each year should be made aware of this, some experts say. But the frustrating truth is, scientists are still trying to figure out in which cases having an appendix is protective and in which we may be better off without it.

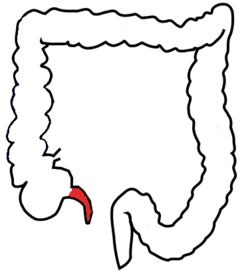

The appendix is a blind pouch (meaning its ending is closed off) that extends from the large intestine. Not all mammals have one; it's been found in several species of primates and rodents, as well as in rabbits, wombats, and Florida manatees, among others (dogs and cats don't have it). While a human appendix "looks like a little worm," Smith said, these anatomical structures come in various sizes and shapes. Some are thick, as in a beaver, while others are long and spiraling, like a rabbit's.

Comparative anatomy studies reveal that the appendix has evolved independently at least 29 times throughout mammalian evolution. This suggests that "it has some kind of an adaptive function," Smith said. When French scientists analyzed data from 258 species of mammals, they discovered that those that possess an appendix live longer than those without one. A possible explanation, the researchers wrote, may lie with the appendix's role in preventing diarrhea.

Their 2023 study supported this hypothesis. Based on veterinary records of 45 different species of primates housed in a French zoo, the scientists established that primates with appendixes are far less likely to suffer severe diarrhea than those that don't possess this organ. The appendix, it appears, might be our tiny weapon against bowel troubles.

For immunologist William Parker, PhD, a visiting scholar at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, these data are "about as good as we could hope for" in support of the idea that the appendix might protect mammals from GI problems. An experiment on humans would be unethical, Parker said. But observational studies offer clues.

One study showed that compared with people with an intact appendix, young adults with a history of appendectomy have more than double the risk of developing a serious infection with non-typhoidal Salmonella of the kind that would require hospitalization.

A "Safe House" for Bacteria

Such studies add weight to a theory that Parker and his colleagues developed back in 2007: That the appendix acts as a "safe house" for beneficial gut bacteria.

Think of the colon as a wide pipe, Parker said, that may become contaminated with a pathogen such as Salmonella. Diarrhea follows, and the pipe gets repeatedly flushed, wiping everything clean, including your friendly gut microbiome. Luckily, "you've got this little offshoot of that pipe," where the flow can't really get in "because it's so constricted," Parker said. The friendly gut microbes can survive inside the appendix and repopulate the colon once diarrhea is over. Parker and his colleagues found that the human appendix contains a thick layer of beneficial bacteria. "They were right where we predicted they would be," he said.

This safe house hypothesis could explain why the gut microbiome may be different in people who no longer have an appendix. In one small study, people who'd had an appendectomy had a less diverse microbiome, with a lower abundance of beneficial strains such as Butyricicoccus and Barnesiella, than did those with intact appendixes.

The appendix likely has a second function, too, Smith said: It may serve as a training camp for the immune system. "When there is an invading pathogen in the gut, it helps the GI system to mount the immune response," she said. The human appendix is rich in special cells known as M cells. These act as scouts, detecting and capturing invasive bacteria and viruses and presenting them to the body's defense team, such as the T lymphocytes.

If the appendix shelters beneficial bacteria and boosts immune response, that may explain its links to various diseases. According to an epidemiological study from Taiwan,patients who underwent an appendectomy have a 46% higher risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) — a disease associated with a low abundance of Butyricicoccus bacteria. This is why, the study authors wrote, doctors should pay careful attention to people who've had their appendixes removed, monitoring them for potential symptoms of IBS.