The following article in a popular magazine follows up on research that came out last year about the alarming steep decline in male sperm counts and sperm concentration over the past few decades. This is true for the U.S., Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and it is thought world wide. The article discusses the causes: environmental chemicals and plastics, especially those that are endocrine disruptors (they disrupt a person's hormones!). These chemicals are all around us, and we all have some in our bodies (but the amounts and types vary from person to person). Some examples of such chemicals are parabens, phthalates, BPA and BPA substitutes.

The following article in a popular magazine follows up on research that came out last year about the alarming steep decline in male sperm counts and sperm concentration over the past few decades. This is true for the U.S., Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and it is thought world wide. The article discusses the causes: environmental chemicals and plastics, especially those that are endocrine disruptors (they disrupt a person's hormones!). These chemicals are all around us, and we all have some in our bodies (but the amounts and types vary from person to person). Some examples of such chemicals are parabens, phthalates, BPA and BPA substitutes.

Even though there are effects from these chemicals throughout life, some of the worst effects from these chemicals seem to be during pregnancy - with a big effect on the developing male fetus. Testosterone levels in men are also dropping. Bottom line: males are becoming "less male", especially due to their exposure to all these chemicals when they are developing before birth (fetal exposure). Since it is getting worse with every generation of males, the concern is that soon males may be unable to father children because their sperm count will be too low - infertility. Dogs are experiencing the same decline in fertility!

Why isn't there more concern over this? What can we do? We all use and need plastic products, but we need to use safer chemicals in products, ones that won't mimic hormones and have endocrine disrupting effects. Remember, these chemicals have more effects on humans than just sperm quality (here and here). While you can't totally avoid plastics and endocrine disrupting chemicals, you can definitely lower your exposure. And it's most important before conception (levels of these chemicals in both parents), during pregnancy, and during childhood.

Do go read the whole article. Excerpts from Daniel Noah Halpern's article in GQ: Sperm Count Zero

A strange thing has happened to men over the past few decades: We’ve become increasingly infertile, so much so that within a generation we may lose the ability to reproduce entirely. What’s causing this mysterious drop in sperm counts—and is there any way to reverse it before it’s too late?

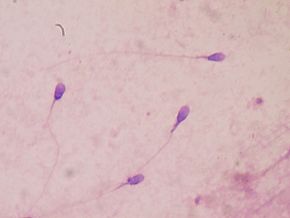

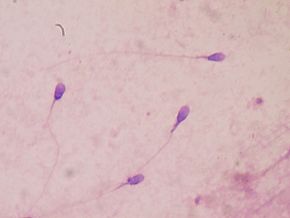

Last summer a group of researchers from Hebrew University and Mount Sinai medical school published a study showing that sperm counts in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have fallen by more than 50 percent over the past four decades. (They judged data from the rest of the world to be insufficient to draw conclusions from, but there are studies suggesting that the trend could be worldwide.) That is to say: We are producing half the sperm our grandfathers did. We are half as fertile.

The Hebrew University/Mount Sinai paper was a meta-analysis by a team of epidemiologists, clinicians, and researchers that culled data from 185 studies, which examined semen from almost 43,000 men. It showed that the human race is apparently on a trend line toward becoming unable to reproduce itself. Sperm counts went from 99 million sperm per milliliter of semen in 1973 to 47 million per milliliter in 2011, and the decline has been accelerating. Would 40 more years—or fewer—bring us all the way to zero?

I called Shanna H. Swan, a reproductive epidemiologist at Mount Sinai and one of the lead authors of the study, to ask if there was any good news hiding behind those brutal numbers. Were we really at risk of extinction? She failed to comfort me. “The What Does It Mean question means extrapolating beyond your data,” Swan said, “which is always a tricky thing. But you can ask, ‘What does it take? When is a species in danger? When is a species threatened?’ And we are definitely on that path.” That path, in its darkest reaches, leads to no more naturally conceived babies and potentially to no babies at all—and the final generation of Homo sapiens will roam the earth knowing they will be the last of their kind.

The results, when they came in, were clear. Not only were sperm counts per milliliter of semen down by more than 50 percent since 1973, but total sperm counts were down by almost 60 percent: We are producing less semen, and that semen has fewer sperm cells in it. This time around, even scientists who had been skeptical of past analyses had to admit that the study was all but unassailable.

Almost all the scientists I talked to stressed that not only were low sperm counts alarming for what they said about the reproductive future of the species—they were also a warning of a much larger set of health problems facing men. In this view, sperm production is a canary in the coal mine of male bodies: We know, for instance, that men with poor semen quality have a higher mortality rate and are more likely to have diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease than fertile men.

Testosterone levels have also dropped precipitously, with effects beginning in utero and extending into adulthood. One of the most significant markers of an organism's sex is something called anogenital distance (AGD)—the measurement between the anus and the genitals. Male AGD is typically twice the length of female, a much more dramatic difference than height or weight or musculature. Lower testosterone leads to a shorter AGD, and a measurement lower than the median correlates to a man being seven times as likely to be subfertile and gives him a greater likelihood of having undescended testicles, testicular tumors, and a smaller penis. “What you are seeing in a number of systems, other developmental systems, is that the sex differences are shrinking,” Swan told me. Men are producing less sperm. They're also becoming less male.

Eventually, Niels E. Skakkebæk [a pediatric endocrinologist] linked several other previously rare symptoms for a condition he called testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), a collection of male reproductive problems that include hypospadias (an abnormal location for the end of the urethra), cryptorchidism (an undescended testicle), poor semen quality, and testicular cancer. What Skakkebæk proposed with TDS is that these disorders can have a common fetal origin, a disruption in the development of the male fetus in the womb.

So what was causing this disruption? To say there is only a single answer might be an overstatement—stress, smoking, and obesity, for example, all depress sperm counts—but there are fewer and fewer critics of the following theory: The industrial revolution happened. And the oil industry happened. And 20th-century chemistry happened. In short, humans started ingesting a whole host of compounds that affected our hormones—including, most crucially, estrogen and testosterone.

The scientists I talked to were less cautious about embracing this explanation than I expected. Down the hall from Skakkebæk's office, I met Anna-Maria Andersson, a biologist whose research has focused on declining testosterone levels. “There has been a chemical revolution going on starting from the beginning of the 19th century, maybe even a bit before,” she told me, “and upwards and exploding after the Second World War, when hundreds of new chemicals came onto the market within a very short time frame.” Suddenly a vast array of chemicals were entering our bloodstream, ones that no human body had ever had to deal with. The chemical revolution gave us some wonderful things: new medicines, new food sources, faster and cheaper mass production of all sorts of necessary products. It also gave us, Andersson pointed out, a living experiment on the human body with absolutely no forethought to the result.

When a chemical affects your hormones, it's called an endocrine disruptor. And it turns out that many of the compounds used to make plastic soft and flexible (like phthalates) or to make them harder and stronger (like Bisphenol A, or BPA) are consummate endocrine disruptors. Phthalates and BPA, for example, mimic estrogen in the bloodstream. If you're a man with a lot of phthalates in his system, you'll produce less testosterone and fewer sperm. If exposed to phthalates in utero, a male fetus's reproductive system itself will be altered: He will develop to be less male.

Women with raised levels of phthalates in their urine during pregnancy were significantly more likely to have sons with shorter anogenital distance as well as shorter penis length and smaller testes. “When the [fetus's] testicles start making testosterone, which is about week eight of pregnancy, they make a little less,” Swan said. “That's the nub of this whole story. So phthalates decrease testosterone. The testicles then do not produce proper testosterone, and the anogenital distance is shorter.”

The problem is that these chemicals are everywhere. BPA can be found in water bottles and food containers and sales receipts. Phthalates are even more common: They are in the coatings of pills and nutritional supplements; they're used in gelling agents, lubricants, binders, emulsifying agents, and suspending agents. Not to mention medical devices, detergents and packaging, paint and modeling clay, pharmaceuticals and textiles and sex toys and nail polish and liquid soap and hair spray. They are used in tubing that processes food, so you'll find them in milk, yogurt, sauces, soups, and even, in small amounts, in eggs, fruits, vegetables, pasta, noodles, rice, and water. The CDC determined that just about everyone in the United States has measurable levels of phthalates in his or her body—they're unavoidable.

What's more, there is evidence that the effect of these endocrine disruptors increases over generations, due to something called epigenetic inheritance. ....

Can anything be done? Over the past 20 years, there have been occasional attempts to limit the number of endocrine disruptors in circulation, but inevitably the fixes are insubstantial: one chemical removed in favor of another, which eventually turns out to have its own dangers. That was the case with BPA, which was partly replaced by Bisphenol S, which might be even worse for you. The chemical industry, unsurprisingly, has been resistant to the notion that the billions of dollars of revenue these products represent might also represent terrible damage to the human body, and have often followed the model of Big Tobacco and Big Oil—fighting regulation with lobbyists and funding their own studies that suggest their products are harmless.

The following article in a popular magazine follows up on research that came out last year about the alarming steep decline in male sperm counts and sperm concentration over the past few decades. This is true for the U.S., Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and it is thought world wide. The article discusses the causes: environmental chemicals and plastics, especially those that are endocrine disruptors (they disrupt a person's hormones!). These chemicals are all around us, and we all have some in our bodies (but the amounts and types vary from person to person). Some examples of such chemicals are parabens, phthalates, BPA and BPA substitutes.

The following article in a popular magazine follows up on research that came out last year about the alarming steep decline in male sperm counts and sperm concentration over the past few decades. This is true for the U.S., Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and it is thought world wide. The article discusses the causes: environmental chemicals and plastics, especially those that are endocrine disruptors (they disrupt a person's hormones!). These chemicals are all around us, and we all have some in our bodies (but the amounts and types vary from person to person). Some examples of such chemicals are parabens, phthalates, BPA and BPA substitutes.

Any thoughts as how to cleanse the chemicals from our systems, some kind of detox?

You can quickly improve (within a week or 2) what is in your body by making some changes - such as increasing the organic foods you eat (immediate decrease in pesticides in your body), avoiding fragrances, antimicrobial products, anti-stain products, pesticides. (Full list here)

Avoid dryer sheets (chemicals coat your clothes). Eat fewer canned foods (all cans have chemical linings, even if it says BPA free). Look for and store foods/juices in glass containers when possible.

Don't use non-stick pots and pans (e.g., instead use stainless steel).

It's a life-style change, but the results show up in the blood and urine quickly.

Think of it this way: everything you are exposed to gets into you through inhalation, ingestion, or absorption through the skin.

The liver normally does any needed detox, so nothing more is needed.