A number of people contacting me have indicated that living in a house or apartment with a mold problem led to their chronic sinusitis. And it wasn't the dreaded toxic black mold (varieties of mold which can cause serious neurological symptoms), but common molds that triggered their inflammatory reactions, respiratory symptoms, allergies, and eventually chronic sinusitis. All due to excessive mold exposure.

A number of people contacting me have indicated that living in a house or apartment with a mold problem led to their chronic sinusitis. And it wasn't the dreaded toxic black mold (varieties of mold which can cause serious neurological symptoms), but common molds that triggered their inflammatory reactions, respiratory symptoms, allergies, and eventually chronic sinusitis. All due to excessive mold exposure.

This summer's flooding caused by hurricanes and tropical storms will result in major mold growth in residences after the water recedes. What will be the health consequences? Article excerpts about mold (and with impressive photos) from The Atlantic:

The Looming Consequences of Breathing Mold

But the impact of hurricanes on health is not captured in the mortality and morbidity numbers in the days after the rain. This is typified by the inglorious problem of mold. Submerging a city means introducing a new ecosystem of fungal growth that will change the health of the population in ways we are only beginning to understand. The same infrastructure and geography that have kept this water from dissipating created a uniquely prolonged period for fungal overgrowth to take hold, which can mean health effects that will bear out over years and lifetimes.

The documented dangers of excessive mold exposure are many. Guidelines issued by the World Health Organization note that living or working amid mold is associated with respiratory symptoms, allergies, asthma, and immunological reactions. The document cites a wide array of “inflammatory and toxic responses after exposure to microorganisms isolated from damp buildings, including their spores, metabolites, and components,” as well as evidence that mold exposure can increase risks of rare conditions like hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic alveolitis, and chronic sinusitis.

Twelve years ago in New Orleans, Katrina similarly rendered most homes unlivable, and it created a breeding ground for mosquitoes and the diseases they carry, and caused a shortage of potable water and food. But long after these threats to human health were addressed, the mold exposure, in low-income neighborhoods in particular, continued. The same is true in parts of Brooklyn, where mold overgrowth has reportedly worsened in the years since Hurricane Sandy. In the Red Hook neighborhood, a community report last October found that a still-growing number of residents were living in moldy apartments.

The highly publicized “toxic mold”—meaning the varieties that send mycotoxins into the air, the inhaling of which can acutely sicken anyone—causes most concern right after a flood. In the wake of Hurricane Matthew in South Carolina last year, sludge stood feet deep in homes for days. As it receded, toxic black mold grew. In one small community, Nichols, it was more the mold than the water itself that left the town’s 261 homes uninhabitable for months.

The more insidious and ubiquitous molds, though, produce no acutely dangerous mycotoxins but can still trigger inflammatory reactions, allergies, and asthma. The degree of impact from these exposure in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina is still being studied.

Molds also emit volatile chemicals that some experts believe could affect the human nervous system. Among them is Joan Bennett, a distinguished professor of plant biology and pathology at Rutgers University, who has devoted her career to the study of fungal toxins. She was living in New Orleans during the storm, and she recalls that while some health experts were worried about heavy-metal poisoning or cholera, she was worried about fungus.

The smell of the fungi in her house got so strong after the flooding that it gave her headaches and made her nauseated. As she evacuated, wearing a mask and gloves, she took samples of the mold along with her valued possessions. Her lab at Rutgers went on to report that the volatile organic compounds emitted by the mold, known as mushroom alcohol, had some bizarre effects on fruit flies. For one, they affected genes involved in handling and transporting dopamine in a way that mimicked the pathology of Parkinson’s disease in humans. “More biologists ought to be looking at gas-phase compounds, because I’m quite certain we’ll find a lot of unexpected effects that we’ve been ignoring,” said Bennett.

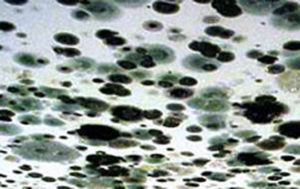

Mold in ceiling. Credit: CDC

Mold in ceiling. Credit: CDC