Great idea and one that this blog has been pushing for a long time - the use of beneficial bacteria to get rid of other harmful bacteria. Some researchers refer to the bacteria acting as "living antibiotics" when they overpower harmful bacteria.

Great idea and one that this blog has been pushing for a long time - the use of beneficial bacteria to get rid of other harmful bacteria. Some researchers refer to the bacteria acting as "living antibiotics" when they overpower harmful bacteria.

Researchers such as Daniel Kadouri, a micro-biologist at Rutgers School of Dental Medicine in Newark, are studying bacteria that aggressively attack harmful bacteria, and calling them "predator bacteria". They are focusing on one specific bacteria - Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, a gram-negative bacteria that dines on other gram-negative bacteria. They hope to eventually be able to give this bacteria as a medicine to humans , and then this predator bacteria would overpower and destroy "superbugs" (pathogenic bacteria that are resistant to many antibiotics). A great idea, but unfortunately the researchers think that it'll take about 10 more years of testing and development before it's ready for use in humans. From Science News:

Live antibiotics use bacteria to kill bacteria

The woman in her 70s was in trouble. What started as a broken leg led to an infection in her hip that hung on for two years and several hospital stays. At a Nevada hospital, doctors gave the woman seven different antibiotics, one after the other. The drugs did little to help her. Lab results showed that none of the 14 antibiotics available at the hospital could fight the infection, caused by the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae.... The CDC’s final report revealed startling news: The bacteria raging in the woman’s body were resistant to all 26 antibiotics available in the United States. She died from septic shock; the infection shut down her organs.

Kallen estimates that there have been fewer than 10 cases of completely resistant bacterial infections in the United States. Such absolute resistance to all available drugs, though incredibly rare, was a “nightmare scenario,” says Daniel Kadouri, a micro-biologist at Rutgers School of Dental Medicine in Newark, N.J. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria infect more than 2 million people in the United States every year, and at least 23,000 die, according to 2013 data, the most recent available from the CDC.

It’s time to flip the nightmare scenario and send a killer after the killer bacteria, say a handful of scientists with a new approach for fighting infection. The strategy, referred to as a “living antibiotic,” would pit one group of bacteria — given as a drug and dubbed “the predators” — against the bacteria that are wreaking havoc among humans.

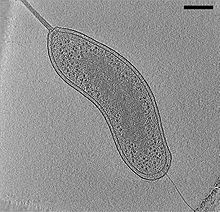

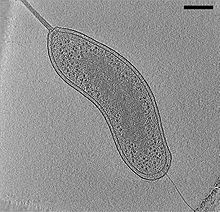

The notion of predatory bacteria sounds a bit scary, especially when Kadouri likens the most thoroughly studied of the predators, Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, to the vicious space creatures in the Alien movies. B. bacteriovorus, called gram-negative because of how they are stained for microscope viewing, dine on other gram-negative bacteria. All gram-negative bacteria have an inner membrane and outer cell wall. The predators don’t go after the other main type of bacteria, gram-positives, which have just one membrane.

“It’s a very efficient killing machine,” Kadouri says. That’s good news because many of the most dangerous pathogens that are resistant to antibiotics are gram-negative (SN: 6/10/17, p. 8), according to a list released by the WHO in February. It’s the predator’s hunger for the bad-guy bacteria, the ones that current drugs have become useless against, that Kadouri and other researchers hope to harness. Pitting predatory against pathogenic bacteria sounds risky. But, from what researchers can tell, these killer bacteria appear safe. “We know that [B. bacteriovorus] doesn’t target mammalian cells,” Kadouri says.

Predatory bacteria can efficiently eat other gram-negative bacteria, munch through biofilms and even save zebrafish from the jaws of an infectious death. But are they safe? Kadouri and the other researchers have done many studies, though none in humans yet, to try to answer that question.... Other studies looking for potential toxic effects of B. bacteriovorus have so far found none. Both Mitchell and Kadouri tested B. bacteriovoruson human cells and found that the predatory bacteria didn’t harm the cells or prompt an immune response. The researchers separately reported their findings in late 2016 in Scientific Reports and PLOS ONE.

Bdellovibrio bacteriovirus Credit: Wikipedia

Bdellovibrio bacteriovirus Credit: Wikipedia