Evidence is accumulating that engaging in exercise may not only prevent cancer, but that in those who already have cancer - it may prevent progression of the cancer. Fantastic!

Evidence is accumulating that engaging in exercise may not only prevent cancer, but that in those who already have cancer - it may prevent progression of the cancer. Fantastic!

A large 2019 review of 9 studies (755,459 individuals) found that 2 1/2 hours per week of "moderate-intensity" physical activity or exercise (e.g. brisk walks) really lowers the risk of 7 cancers: colon, breast, endometrial, kidney, myeloma, liver, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Some (but not all) were lowered in a dose response manner, that is, the more exercise (up to 5 hours per week), the bigger the protective effect.

Another 2019 review article stated that there are hundreds of studies in the field of "exercise oncology" which have examined the effect of exercise on cancer in humans. The studies find that exercise may prevent cancer, control cancer progression, and interact positively with anticancer therapies. (One example: a study found regular moderate or vigorous physical activity is associated with lower rates of death in men diagnosed with prostate cancer.)

In addition, hundreds of animal (mice and rat) and laboratory studies show that the anticancer effects of exercise are causal, not just an association. There is evidence that each exercise session actually has an effect on cancer tumors. And that the more exercise sessions, the bigger the effect!

Bottom line: Get out and move, move, move! Plan to do this every week for years.

An infographic that illustrates how exercise has anticancer effects, from The Scientist: Infographic: Exercise’s Anticancer Mechanisms

Excerpts from the accompanying April 2020 article by Prof. Bente K. Pedersen (Univ. of Copenhagen) on how regular exercise has anticancer effects. From The Scientist: Regular Exercise Helps Patients Combat Cancer

Physical exercise is increasingly being integrated into the care of cancer patients such as Mathilde, and for good reason. Evidence is accumulating that exercise improves the well being of these patients by combating the physical and mental deterioration that often occur during anticancer treatments. Most remarkably, we are beginning to understand that exercise can directly or indirectly fight the cancer itself.

An increasing amount of epidemiological literature strongly indicates that exercise training may lower the risk of cancer, control disease progression, amplify the effects of anticancer therapy, and improve physical function and psychosocial outcomes. For example, a 2016 study of more than 1.4 million individuals in the US and Europe found that people could reduce their cancer risk with moderate to vigorous leisure-time exercise training. The phenomenon held across several different cancers, including breast, colon, rectum, esophagus, lung, liver, kidney, bladder, and head and neck.

And the combined results of approximately 700 unique exercise intervention trials, involving more than 50,000 cancer patients in total, leave little doubt that patients benefit from physical activity, showing improvements such as reduced toxicity of anticancer treatment, decreased disease progression, and enhanced survival. The same studies showed that exercise training improves mood, decreases loss of muscle mass, and helps cancer patients return to work earlier after successful treatment. Some studies show that 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise nearly double the chance of survival compared with breast cancer patients who don’t exercise during treatments.

Regardless of the nature of the training, the primary setting of exercise’s effect on cancer is the bloodstream. Long-term training has been associated with a reduction in the blood levels of systemic risk factors, such as sex hormones, insulin, and inflammatory molecules. ...

To learn more about the effects of individual bouts of exercise versus long-term training regimens, Christine Dethlefsen, a graduate student in my laboratory, incubated breast cancer cells with serum obtained from cancer survivors at rest before and after a six-month training intervention that began after patients completed primary surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. For comparison, she incubated other cells with serum obtained from blood drawn from these patients immediately after a two-hour acute exercise session during their weeks-long course of chemotherapy. Her study revealed that serum obtained following an exercise session reduced the viability of the cultured breast cancer cells, while serum drawn at rest following six months of training had no effect.

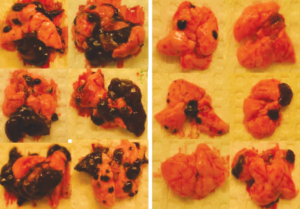

These data suggest that cancer-fighting effects are driven by repeated acute exercise, and each bout matters. In Dethlefsen’s study, incubation with serum obtained after a single bout of exercise (consisting of 30 minutes of warm-up, 60 minutes of resistance training, and a 30-minute high-intensity interval spinning session) reduced breast cancer cell viability by only 10 to 15 percent compared with control cells incubated with serum obtained at rest. But a reduction in tumor cell viability by 10 to 15 percent several times a week may add up to clinically significant inhibition of tumor growth. Indeed, in a separate study, my colleagues and I found that daily, voluntary wheel running in mice inhibits tumor progression across a range of tumor models and anatomical locations, typically by more than 50 percent.

Credit: L. PEDERSEN ET AL., CELL METAB, 2016