Of course there is a lung microbiome. From The Scientist:

Breathing Life into Lung Microbiome Research

Although it’s far less populated than the mouth community that helps feed it, researchers increasingly appreciate the role of the lung microbiome in respiratory health.

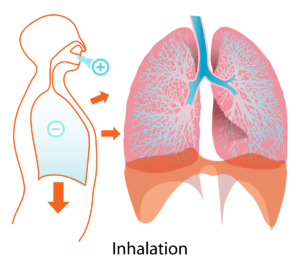

“There’s a constant flow into [the] lungs of aspirated bacteria from the mouth,” he said. But through the action of cilia and the cough reflex, among other things, there’s also an outward flow of microbes, making the lung microbiome a dynamic community.

Like the placenta, urethra, and other sites of the body now known to harbor commensal bacteria, researchers and clinicians once considered the lung to be sterile in the absence of infection. Over the last 10 years, however, evidence has been building that, although it is far less-populated than the mouth or gut, the disease-free lung, too, is populated by a persistent community of bacteria. Shifts in the lung microbiome have been correlated with the development of chronic lung conditions like cystic fibrosis (CF) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), although the relationship between the lung microbiome and disease is complicated.

The surface area of the healthy lung is a dynamic environment. The respiratory organ is constantly bombarded by debris and microbes that make their way from the mouth and nose through the trachea. Ciliated cells on branching bronchioles within the lungs beat rhythmically to move debris and invading microbes, while alveolar macrophages constantly patrol for and destroy unwelcome bugs.

The lung microbiome is about 1,000 times less dense than the oral microbiome and about 1 million to 1 billion times sparser than the microbial community of the gut, said Huffnagle. That is in part because the lung lacks the microbe-friendly mucosal lining found in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract, instead harboring a thin layer of much-less-inviting surfactant to keep the respiratory organs from drying out. ... It appears that the lung microbiome is populated from the oral microbiome, and among this population exists a small subset of bacteria that can survive the unique environment of the lung. The most common bacteria found in healthy lungs are Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Veillonella species.

Segal, who studies small airway disorders with an eye toward early detection of COPD, has found in a series of studies that inflammation of the lungs is often accompanied by a shift in their bacterial makeup. The mechanism behind these changes and consequences of them are still not well understood, however. Other studies have uncovered associations between changes in the lung microbiome and HIV or asthma, but again, causality has been difficult to elucidate.

According to Yvonne Huang from the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, who is working to characterize lung microbiomes in relation to health and disease progression, “this field is where studies of gut microbiome were 10 to 15 years ago.

Human lungs. Credit: Wikipedia

Human lungs. Credit: Wikipedia