An interesting Canadian study that followed young children for 3 years found that young infants may be more likely to develop allergic asthma if they lack four beneficial bacteria in their gut. Children with low levels of Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia bacteria in their gut in their first 3 months were at higher risk for asthma and tended to receive more antibiotics than healthier children before they turned 1 year old.

An interesting Canadian study that followed young children for 3 years found that young infants may be more likely to develop allergic asthma if they lack four beneficial bacteria in their gut. Children with low levels of Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia bacteria in their gut in their first 3 months were at higher risk for asthma and tended to receive more antibiotics than healthier children before they turned 1 year old.

Other studies have shown that the risk of developing asthma and allergies has been linked with such things as taking antibiotics, cesarean birth, bottle fed with formula, not living on a farm, and not having furry pets in the first year of life.

The researchers wrote: "Our findings indicate that in humans, the first 100 days of life represent an early-life critical window in which gut microbial dysbiosis {the microbial community being out of whack} is linked to the risk of asthma and allergic disease." How do the infants get these microbes? It is thought that infants get exposed to the mother's microbiome (microbial community) via vaginal birth, breast-milk, and mouth contact with the mother's skin. From NPR News:

Missing Microbes Provide Clues About Asthma Risk

The composition of the microbes living in babies' guts appears to play a role in whether the children develop asthma later on, researchers reported Wednesday. The researchers sampled the microbes living in the digestive tracts of 319 babies, and followed up on the children to see if there was a relationship between their microbes and their risk for the breathing disorder. In the journal Science Translational Medicine, the researchers report Wednesday that those who had low levels of four bacteria were more likely to develop asthma by the time they were 3-years-old.

Specifically, the researchers focused on 22 children who showed early signs of asthma, such as wheezing, when they were 1-year-old. They were much more likely than the other children to have had low levels of the four bacteria when they were 3-months-old. By the time they turned 3, most had developed full-blown asthma."The bottom line is that if you have these four microbes in high levels you have a very low risk of getting asthma," says Brett Finlay, a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia who helped conduct the research. "If you don't have these four microbes or low levels of these microbes you have a much greater chance of asthma."

Asthma is a common and growing problem among children. Evidence has been accumulating that one reason may be a disruption in the healthful microbes children get early in life, Finlay says."There's all these smoking guns like, for example, if you breast-feed versus bottle feed you have less asthma," he says. "If you're born by C-section instead of vaginal birth you have a 20 percent higher rate of asthma. If you get antibiotics in the first year of life you have more asthma." The microbiomes of kids who aren't breast-fed and are born by Caesarean section may miss out on getting helpful bugs. Antibiotics can kill off the good bacteria that seem important for the development of healthy immune systems.

"What's become clear recently is that microbes play a major role in shaping how the immune system develops. And asthma is really an immune allergic-type reaction in the lungs," Finlay says. "And so our best guess is the way these microbes are working is they are influencing how our immune system is shaped really early in life."

To further test their theory, the researchers gave laboratory mice bred to have a condition resembling asthma in humans the four missing microbes. The intervention reduced the signs of levels of inflammation in their lungs, which is a risk factor for developing asthma.

The bacteria are from four genuses: Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium and Rothia. The researchers aren't exactly sure how the microbes may protect against asthma. But babies with few or none of them had low levels of a substance known as acetate, which is believed to be involved with regulating the immune system.

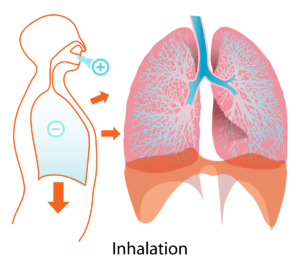

Human lungs. Credit: Wikipedia

Human lungs. Credit: Wikipedia