The following article is about Dr. Janelle Ayres, a researcher in California, working on "beneficial bacteria" to help the body tolerate infections. This is different than the usual medical approach of fighting infections - where antibiotics are used to kill microbes. Reading the article, my first thought was "Well, duh....of course this approach works." This is what we've been doing in using Lactobacillus sakei, a beneficial bacteria, in successfully treating sinusitis since early 2013! ..... The good news in reading this article is that using bacteria to treat infections or diseases seems to finally be going mainstream.

The following article is about Dr. Janelle Ayres, a researcher in California, working on "beneficial bacteria" to help the body tolerate infections. This is different than the usual medical approach of fighting infections - where antibiotics are used to kill microbes. Reading the article, my first thought was "Well, duh....of course this approach works." This is what we've been doing in using Lactobacillus sakei, a beneficial bacteria, in successfully treating sinusitis since early 2013! ..... The good news in reading this article is that using bacteria to treat infections or diseases seems to finally be going mainstream.

Ayres, and some of her colleagues, are interested in why some people can deal with infections, or can repair damaged tissue even during bouts of serious disease, while other people succumb to the disease. She believes she can develop drugs that will boost those qualities in patients who lack them, and help keep people alive through battles with sepsis, malaria, cholera, and a host of other diseases. Their approach looks at "tolerance" — which is a body’s ability to minimize damage while infected, and she calls it the “tolerance defense system.”

She is focusing on this approach because she feels that drugs that target bacteria (such as antibiotics) become useless because the bacteria evolve to resist those drugs. Instead, she thinks we can harness bacteria (even ones normally classified as pathogens) to make new drugs. Her approach to treating an infection could be summarized as: Don't fight it. Help the body tolerate it. Excerpts from STAT News:

As her father lay dying of sepsis, Janelle Ayres spent nine agonizing days at his bedside. When he didn’t beat the virulent bloodstream infection, she grieved. And then she got frustrated. She knew there had to be a better way to help patients like her dad. In fact, she was working on one in her lab. Ayres, a hard-charging physiologist who has unapologetically decorated her lab with bright touches of hot pink, is intent on upending our most fundamental understanding of how the human body fights disease.

Scientists have focused for decades on the how the immune system battles pathogens. Ayres believes other elements of our physiology are at least as important — so she’s hunting for the beneficial bacteria that seem to help some patients maintain a healthy appetite and repair damaged tissue even during bouts of serious disease. If she can find them — and she’s already begun to do so — she believes she can develop drugs that will boost those qualities in patients who lack them and help keep people alive through battles with sepsis, malaria, cholera, and a host of other diseases. Her approach, in a nutshell: Stop worrying so much about fighting infections. Instead, help the body tolerate them.

An associate professor at the Salk Institute in the heart of San Diego’s booming biotech beach, Ayres is harnessing all manner of high-tech tools from the fields of microbiomics, genetics, and immunology — and looking to a menagerie of animals — to sort out why some individuals tolerate infection so much better than others. It’s work that’s desperately needed, Ayres said, as it becomes ever more clear that our standard approach to fighting infection using antibiotics and antivirals is hopelessly inadequate. The drugs don’t work for all diseases, they kill off good bacteria along with bad — and their wanton use is contributing to the rise of antibiotic resistant bacteria, or “superbugs,” which terrify disease experts because there are few ways to stop them.

....They went on to propose that the immune response to pathogens wasn’t the whole story, and that tolerance — a body’s ability to minimize damage while infected — may play a key role as well. Ayres has since gone on to call what she studies the “tolerance defense system.”

Society needs drugs that don’t target bacteria, which can so quickly evolve to evade our best medicines, she argues. Instead, she thinks we can harness those bacteria — even the ones normally classified as pathogens — to make new drugs that save lives by targeting an infected person’s tissues and organs. That would be an entirely new class of therapeutics, which could lessen our dependence on antibiotics and help save lives in cases, like her father’s, where antibiotics fail.

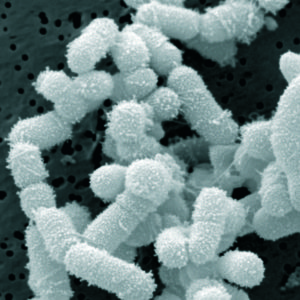

She’s been working furiously in her own lab, rolling out a series of studies that have found critical targets for new drugs. Her main focus: the trillions of bacteria — known collectively as the microbiome — that reside in our bodies but do not sicken us. Ayres suspects they might play a key role in the tolerance defense system. But if bacteria do help increase tolerance to disease, what strains are involved and what exactly are they doing?