The issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment has recently been in the news, especially when discussing breast cancer, prostate cancer, and thyroid cancer. Meaning too much unnecessary treatment with harms, when the best approach would have been to do nothing, as studies have suggested or actually shown. Now here is an article in Medscape suggesting that rather than be quick to operate or treat, the best approach for nearly 70% of prostate cancers may be just "watching".

The issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment has recently been in the news, especially when discussing breast cancer, prostate cancer, and thyroid cancer. Meaning too much unnecessary treatment with harms, when the best approach would have been to do nothing, as studies have suggested or actually shown. Now here is an article in Medscape suggesting that rather than be quick to operate or treat, the best approach for nearly 70% of prostate cancers may be just "watching".

The U.S. Preventive Task Force, which analyzes the value of screening tests, in May 2012 recommended AGAINST routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening for prostate cancer for all age groups. According to them, studies do not show that benefits of routine screening of asymptomatic prostate cancer and the resulting treatment outweigh the harms of treatment (e.g., surgical complications including death from surgery, erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, bowel dysfunction, and bladder dysfunction), or that prostate cancer treatment even reduces mortality (deaths).

They point out that: "There is convincing evidence that PSA-based screening programs result in the detection of many cases of asymptomatic prostate cancer. There is also convincing evidence that a substantial percentage of men who have asymptomatic cancer detected by PSA screening have a tumor that either will not progress or will progress so slowly that it would have remained asymptomatic for the man's lifetime. The terms "overdiagnosis" or "pseudo-disease" are used to describe both situations." (NOTE: others have argued against this recommendation)

When reading the full Medscape article, it was pointed out that in the study being discussed, one person who was offered active surveillance but declined and was treated with an immediate radical prostatectomy, still died of metastatic prostate cancer. This was an example of a case where when the disease is truly aggressive, it may have spread "like a bird" throughout the body (in Dr. H. Gilbert Welch's terms in his books Overdiagnosed and Less Medicine, More Health) from the very beginning, and may be unstoppable no matter what is done.

I have also noticed reading other prostate cancer studies that a certain percentage of prostate cancers regress from the point of diagnosis (the PSA test and biopsy). In other words, researchers are finding that cancer can have different paths: regresses, stays the same, grows slowly (and can be treated when symptoms appear), or grows very quickly and is so aggressive and unstoppable that it goes through the body "like a bird". And we don't know which will be the aggressive ones when we first find them, thus the controversies over what to do: screen or not?, and treat or not? From Medscape:

Nearly 70% of US Prostate Cancers Could Be Watched

More than two-thirds (68%) of all prostate cancers in the United States qualify for active surveillance, according to a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Urology. And if a more stringent definition of surveillance eligibility is used, 44% of cases would be candidates for monitoring instead of immediate treatment, say senior author Ian M. Thompson III, MD, from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and colleagues. These "target" figures are especially credible because they come from a population-based study funded by the National Cancer Institute, and the 3828 participants from Texas undergo regular prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing.

Of the 320 men in the cohort who developed prostate cancer from 2000 to 2012, 281 had data that were sufficient to allow scoring on very detailed surveillance scorecard.Disease characteristics, such as a high Gleason score, rendered 131 of the 320 men ineligible for active surveillance. But 123 of the men (44%) met a conservative set of criteria and were eligible for surveillance.These "lowest-risk" patients had a PSA density below 15%, fewer than three cores involved with cancer, a Gleason score of 6 or less, and cancer involving 50% of biopsy volume or less. Another 64 men (24%) were eligible when a more expansive set of criteria was used. These "higher-risk" men had fewer than five cores with Gleason 3 + 3 cancer and only one core of Gleason 3 + 4 cancer with up to 15% of the core involved with the Gleason 3 + 4 disease.

When the two groups were combined, 187 patients (68%) were eligible for active surveillance. Predictably, the number of men who actually chose active surveillance was much lower. From 2000 to 2007, 11% of the men diagnosed with prostate cancer opted for surveillance. From 2007 to 2012, 35% of the men opted for surveillance.

Active surveillance should be offered to "an expanded population of well-informed men who may value preserving function above a small risk of disease progression," write Marc Dall'Era, MD, from the University of California, Davis, and Peter Carroll, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial. In other words, the approach is not just for the lowest-risk cases, they opine.They explain that "the risks of adverse disease-specific outcomes will likely be higher with the inclusion of men with more intermediate-risk features." However, the "absolute risk may still be low," they write.

Perhaps even more important, the study authors observe, is that if the well-documented phenomenon of upgrading or upstaging "truly translated to subsequent consequential outcomes," then "far greater" rates of disease progression, metastases, and death would have been reported in other series of patients. And that has not happened.

The pair also point to the current study as proof that active surveillance is a reasonable approach, not just for "very-low-risk" disease, but for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer, too.

Notably, two of the 320 patients in the Texas cohort either experienced metastatic disease or died of prostate cancer. One of these patients met the expanded criteria and was eligible for active surveillance. "While this could argue against active surveillance, it is notable that this patient underwent radical prostatectomy immediately following diagnosis," the authors explain. The other patient, who was ineligible for surveillance under either definition, was treated definitively but experienced disease progression.

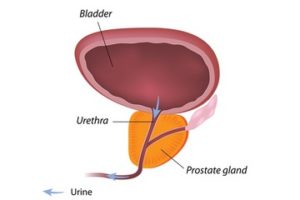

The prostate gland is located beneath a man's bladder. Credit: Live science, Alila Medical Media

The prostate gland is located beneath a man's bladder. Credit: Live science, Alila Medical Media