Well, this is interesting.... Saline nasal rinses (which are popular among persons with sinus issues) apparently is very helpful if one gets COVID-19. A recent study found that starting daily saline rinses two times per day after COVID-19 symptoms start, significantly lowers the risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19.

Well, this is interesting.... Saline nasal rinses (which are popular among persons with sinus issues) apparently is very helpful if one gets COVID-19. A recent study found that starting daily saline rinses two times per day after COVID-19 symptoms start, significantly lowers the risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19.

To make your own saline nasal rinse: mix 1/2 teaspoon each of baking soda and salt in a cup of bottled or boiled (and then cooled) water. Put it into a saline rinse bottle or nasal bulb syringe and use.

In the study, among persons who did nasal saline rinses - less than 1.3% of the 79 study subjects age 55 and older who enrolled within 24-hours of testing positive for COVID-19 experienced hospitalization. No one died. Symptoms also resolved faster.

Among persons who didn't do nasal saline rinses: 9.47% of patients were hospitalized and 1.5% died in a similar group during the same time frame (Sept. 24 and Dec. 21, 2020).

By the way, all persons in the study were 55 or older, and had preexisting medical conditions such as obesity. Also, adding iodine to the nasal rinses did not make a difference. Plain saline rinses were sufficient.

From Medical Xpress: Twice-daily nasal irrigation reduces COVID-related illness, death

Starting twice daily flushing of the mucus-lined nasal cavity with a mild saline solution soon after testing positive for COVID-19 can significantly reduce hospitalization and death, investigators report.

They say the technique that can be used at home by mixing a half teaspoon each of salt and baking soda in a cup of boiled or distilled water then putting it into a sinus rinse bottle is a safe, effective and inexpensive way to reduce the risk of severe illness and death from coronavirus infection that could have a vital public health impact.

"By giving extra hydration to your sinuses, it makes them function better. If you have a contaminant, the more you flush it out, the better you are able to get rid of dirt, viruses and anything else," says Baxter.

"We found an 8.5-fold reduction in hospitalizations and no fatalities compared to our controls," says senior author Dr. Richard Schwartz, chair of the MCG Department of Emergency Medicine. "Both of those are pretty significant endpoints."

The study appears to be the largest, prospective clinical trial of its kind and the older, high-risk population they studied—many of whom had preexisting conditions like obesity and hypertension—may benefit most from the easy, inexpensive practice, the investigators say.

They found that less than 1.3% of the 79 study subjects age 55 and older who enrolled within 24-hours of testing positive for COVID-19 between Sept. 24 and Dec. 21, 2020, experienced hospitalization. No one died.

By comparison, 9.47% of patients were hospitalized and 1.5% died in a group with similar demographics reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the same timeframe, which began about nine months after SARS-CoV-2 first surfaced in the United States.

"The reduction from 11% to 1.3% as of November 2021 would have corresponded in absolute terms to over 1 million fewer older Americans requiring admission," they write. "If confirmed in other studies, the potential reduction in morbidity and mortality worldwide could be profound."

They knew that the more virus that was present in your body, the worse the impact, Baxter says. "One of our thoughts was: If we can rinse out some of the virus within 24 hours of them testing positive, then maybe we can lower the severity of that whole trajectory," she says, including reducing the likelihood the virus could get into the lungs, where it was doing permanent, often lethal damage to many.

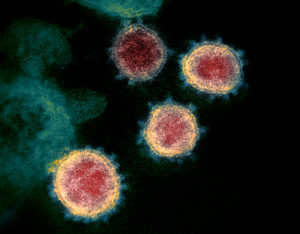

Additionally, the now-infamous spiky SARS-CoV-2 is known to attach to the ACE2 receptor, which is pervasive throughout the body and in abundance in locations like the nasal cavity, mouth and lungs. Drugs that interfere with the virus' ability to attach to ACE2 have been pursued, and Baxter says the nasal irrigation with saline helps decrease the usual robust attachment. Saline appears to inhibit the virus' ability to essentially make two cuts in itself, called furin cleavage, so it can better fit into an ACE2 receptor once it spots one.

Participants self-administered nasal irrigation using either povidone-iodine, that brown antiseptic that gets painted on your body before surgery, or sodium bicarbonate, or baking soda, which is often used as a cleanser, mixed with water that had the same salt concentration normally found in the body.

While the investigators found the additives really added no value, previous research had indicated they might help, for example, make it more difficult for the virus to attach to the ACE2 receptor. But their experience indicates the saline solution alone sufficed. "It's really just the rinsing and the quantity that matter," Baxter says.

The investigators also wanted to know any impact on symptom severity, like chills and loss of taste and smell. Twenty-three of the 29 participants who consistently irrigated twice daily had zero or one symptom at the end of two weeks compared to 14 of the 33 who were less diligent.

Those who completed nasal irrigation twice daily reported quicker resolution of symptoms regardless of which of two common antiseptics they were adding to the saline water.

Study participants and those used as controls had similar ages and rates of common conditions including one or more preexisting health problems.

Older adults, those with obesity and excess weight, who are physically inactive and those with underlying medical conditions are considered most at risk for serious complications and hospitalization from COVID-19. A body mass index, or BMI, which measures weight in relation to height, between 18.5 and 24.9, is considered ideal, and study participants had a mean BMI of 30.3; over 30 indicates obesity.