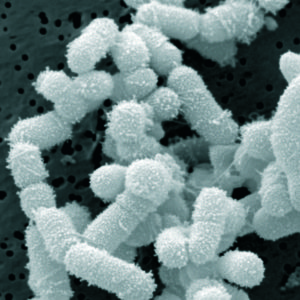

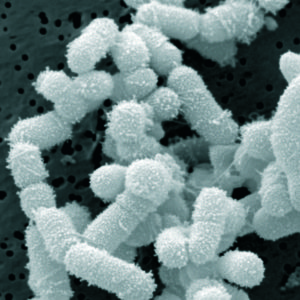

People assume that taking probiotics results in the beneficial probiotic bacteria colonizing and living in the gut (or sinuses when using L. sakei). It is common to hear the phrase "take probiotics to repopulate the gut" or "improve the gut microbes". The human gut microbiota (human gut microbiome) refers to all the microbes that reside inside the gut (hundreds of species). Probiotics are live bacteria, that when taken or administered, result in a health benefit. But what does the evidence say?

People assume that taking probiotics results in the beneficial probiotic bacteria colonizing and living in the gut (or sinuses when using L. sakei). It is common to hear the phrase "take probiotics to repopulate the gut" or "improve the gut microbes". The human gut microbiota (human gut microbiome) refers to all the microbes that reside inside the gut (hundreds of species). Probiotics are live bacteria, that when taken or administered, result in a health benefit. But what does the evidence say?

First, it is important to realize that currently supplements and foods contain only a small variety of probiotic species, with some Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species among the most common. But they are not the most common bacteria found in the gut. And very important bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (a reduction of which is associated with a number of diseases) are not available at all in supplements. One problem is the F. prausnitzii are "oxygen sensitive" and they die within minutes upon exposure to air, a big problem when trying to produce supplements.

The evidence from the last 4 years of L. sakei use for sinusitis treatment is that for some reason, the L. sakei is not sticking around long-term and permanently colonizing in the sinuses. My family's experiences and the experience of other people contacting me is that every time a person becomes sick with a cold or sore throat, it once again results in sinusitis, and then another treatment with a L. sakei product is needed to treat the sinusitis, even though less is needed over time. And of course this has been a surprise and a big disappointment. [See Dec. 2020 update below.]

The same appears to be true for probiotics (whether added to a food or in a supplement) that are taken for other reasons, including intestinal health. Study after study, and a review article, finds that the beneficial bacteria do not colonize in the gut even if there are health benefits from the probiotics. That is, there may be definite health benefits from the bacteria, but within days of stopping the probiotic (whether in a food or a supplement) it is no longer found in the gut. Researchers know this because they can see what bacteria are in the gut by analyzing (using modern genetic sequencing tests) what is in the fecal matter (the stool).

However, the one exception to all of the above is a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) - which is transfer of fecal matter from one person to another. There the transplanted microbes of the donor do colonize the recipient's gut, referred to as "engraftment of microbes". Some researchers found that viruses in the fecal matter helped with the engraftment. So it looks like more than just some bacterial strains are involved. Another thing to remember is that study after study finds that dietary changes result in microbial changes in the gut, and these changes can occur very quickly.

[Dec. 2020 update: A few recent studies are now suggesting that if a person takes or uses a bacterial species that naturally occurs in the body and is depleted, than it may stick around for a while - this is colonization, even if only short-term. We also find this occurring with L. sakei - while we may need to use it now and then, this is occurring less frequently over time, and we need to use a much smaller amount when needed. Colonization! Overall, there has been major improvement of our sinuses over time - and yes, they feel great.]

From Gut Microbiota News Watch: Learning what happens between a probiotic input and a health output

What scientists know is that probiotics in healthy individuals are associated with a number of benefits. Meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials show that probiotics help prevent upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, allergy, and cardiovascular disease risk in adults. But between the input and the output, what happens? A common assumption is that probiotics work by influencing the gut microbe community, leading to an increase in the diversity of bacterial species in the gut ecosystem and measurable excretion in the stool.

But this theory doesn’t seem to be true, according to a recently published systematic review by Kristensen and colleagues in Genome Medicine. Authors of the review analyzed seven studies and found no evidence that probiotics have the ability to change fecal microbiota composition. So even though individuals in the different studies were ingesting live bacterial species, the bacteria didn’t stick around to increase the diversity of the gut fecal microbiota.

“Do probiotics alter the fecal composition of healthy adults? The answer seems to be no,” says Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, Executive Science Officer for the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP)....Dr. Dan Merenstein, Research Division Director and Associate Professor of Family Medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC (USA), agrees. “Initially when probiotics were studied, some people expected to see permanent colonization. We now realize that is unlikely to occur,” he says. “This study shows that the probiotics tested to date do not result in overarching bacterial community structure changes in healthy subjects. But clinical effects are clearly demonstrated for probiotics, and likely some are mediated by microbiome changes.”

At issue, then, is not what probiotics do for healthy individuals, but exactly how they work: the so-called ‘mechanism’. Sanders, who described some alternative mechanisms in her BMC Medicine commentary about the Kristensen review, points out a logical error in news stories worldwide that covered the article: the assumption that if probiotics fail to change the microbiota composition, they fail to have any health effects. Sanders emphasizes that probiotics might work in many possible ways. “Probiotics may act through changing the function of the resident microbes, not their composition. They may interact with host immune cells,” she says. “They may inhibit opportunistic pathogens that are not dominant members of the microbiota. They may promote microbiota stability… .”

In the future, giving specific microbes or entire microbial communities may be part of some cancer treatments! This is because the composition of a person's gut microbiome (the community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses) influences whether a person responds to immunotherapy drugs. This means that the mixture and variety of microbial species living in your intestines may determine whether you respond to cancer immunotherapy drugs. Wow!

In the future, giving specific microbes or entire microbial communities may be part of some cancer treatments! This is because the composition of a person's gut microbiome (the community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses) influences whether a person responds to immunotherapy drugs. This means that the mixture and variety of microbial species living in your intestines may determine whether you respond to cancer immunotherapy drugs. Wow!

People assume that taking probiotics results in the beneficial probiotic bacteria colonizing and living in the gut (or sinuses when using L. sakei). It is common to hear the phrase "take probiotics to repopulate the gut" or "improve the gut microbes". The human gut microbiota (human gut microbiome) refers to all the microbes that reside inside the gut (hundreds of species). Probiotics are live bacteria, that when taken or administered, result in a health benefit. But what does the evidence say?

People assume that taking probiotics results in the beneficial probiotic bacteria colonizing and living in the gut (or sinuses when using L. sakei). It is common to hear the phrase "take probiotics to repopulate the gut" or "improve the gut microbes". The human gut microbiota (human gut microbiome) refers to all the microbes that reside inside the gut (hundreds of species). Probiotics are live bacteria, that when taken or administered, result in a health benefit. But what does the evidence say? For years it has been known that most children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have all sorts of gastrointestinal (GI) problems (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, stomach pain, food intolerance), and the more severe the autism, the more severe the GI problems. Recent studies suggested that a major factor in this are abnormal gut bacteria, with the gut microbial community out of whack (dysbiosis). Previous studies looking at the

For years it has been known that most children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have all sorts of gastrointestinal (GI) problems (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, stomach pain, food intolerance), and the more severe the autism, the more severe the GI problems. Recent studies suggested that a major factor in this are abnormal gut bacteria, with the gut microbial community out of whack (dysbiosis). Previous studies looking at the  The latest development in treating stubborn cases of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) are "poop pills" - pills that patients can easily swallow rather than having to go through a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). The "poop pills" are filled with blenderized fecal matter from healthy donors, are much easier for patients to swallow, and they successfully treat C. difficile at almost the same rate as fecal microbiota transplants - about 91% after 1 or 2 treatments for the pills, and 93 to 96% for FMT. This is an amazing success rate for an infection that debilitates people, is resistant to antibiotics in many cases, and even kills people.

The latest development in treating stubborn cases of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) are "poop pills" - pills that patients can easily swallow rather than having to go through a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). The "poop pills" are filled with blenderized fecal matter from healthy donors, are much easier for patients to swallow, and they successfully treat C. difficile at almost the same rate as fecal microbiota transplants - about 91% after 1 or 2 treatments for the pills, and 93 to 96% for FMT. This is an amazing success rate for an infection that debilitates people, is resistant to antibiotics in many cases, and even kills people.