More long-standing medical advice goes out the window. New advice: avoid diet soda and artificial sweeteners. The amazing part is that our gut bacteria are involved.

More long-standing medical advice goes out the window. New advice: avoid diet soda and artificial sweeteners. The amazing part is that our gut bacteria are involved.

From Science Daily: Certain gut bacteria may induce metabolic changes following exposure to artificial sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners -- promoted as aids to weight loss and diabetes prevention -- could actually hasten the development of glucose intolerance and metabolic disease, and they do so in a surprising way: by changing the composition and function of the gut microbiota -- the substantial population of bacteria residing in our intestines. These findings, the results of experiments in mice and humans, ...says that the widespread use of artificial sweeteners in drinks and food, among other things, may be contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemic that is sweeping much of the world.

For years, researchers have been puzzling over the fact that non-caloric artificial sweeteners do not seem to assist in weight loss, with some studies suggesting that they may even have an opposite effect.

Next, the researchers investigated a hypothesis that the gut microbiota are involved in this phenomenon. They thought the bacteria might do this by reacting to new substances like artificial sweeteners, which the body itself may not recognize as "food." Indeed, artificial sweeteners are not absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, but in passing through they encounter trillions of the bacteria in the gut microbiota.

The researchers treated mice with antibiotics to eradicate many of their gut bacteria; this resulted in a full reversal of the artificial sweeteners' effects on glucose metabolism. Next, they transferred the microbiota from mice that consumed artificial sweeteners to "germ-free," or sterile, mice -- resulting in a complete transmission of the glucose intolerance into the recipient mice. This, in itself, was conclusive proof that changes to the gut bacteria are directly responsible for the harmful effects to their host's metabolism.... A detailed characterization of the microbiota in these mice revealed profound changes to their bacterial populations, including new microbial functions that are known to infer a propensity to obesity, diabetes, and complications of these problems in both mice and humans.

Does the human microbiome function in the same way? Dr. Elinav and Prof. Segal had a means to test this as well. As a first step, they looked at data collected from their Personalized Nutrition Project (www.personalnutrition.org), the largest human trial to date to look at the connection between nutrition and microbiota. Here, they uncovered a significant association between self-reported consumption of artificial sweeteners, personal configurations of gut bacteria, and the propensity for glucose intolerance. They next conducted a controlled experiment, asking a group of volunteers who did not generally eat or drink artificially sweetened foods to consume them for a week, and then undergo tests of their glucose levels and gut microbiota compositions.

The findings showed that many -- but not all -- of the volunteers had begun to develop glucose intolerance after just one week of artificial sweetener consumption. The composition of their gut microbiota explained the difference: the researchers discovered two different populations of human gut bacteria -- one that induced glucose intolerance when exposed to the sweeteners, and one that had no effect either way. Dr. Elinav believes that certain bacteria in the guts of those who developed glucose intolerance reacted to the chemical sweeteners by secreting substances that then provoked an inflammatory response similar to sugar overdose, promoting changes in the body's ability to utilize sugar.

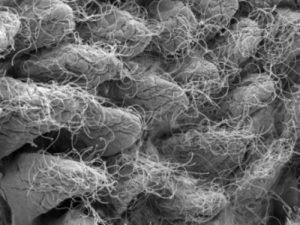

This image depicts gut microbiota. Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

This image depicts gut microbiota. Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science