An article comparing the U.S. versus the European Union's approach to chemicals in products (including in cosmetics, personal care products, and foods), which explains why a number of chemicals are banned in Europe, but allowed in the U.S. From Ensia:

BANNED IN EUROPE, SAFE IN THE U.S.

Atrazine, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says is estimated to be the most heavily used herbicide in the U.S., was banned in Europe in 2003 due to concerns about its ubiquity as a water pollutant.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration places no restrictions on the use of formaldehyde or formaldehyde-releasing ingredients in cosmetics or personal care products. Yet formaldehyde-releasing agents are banned from these products in Japan and Sweden while their levels — and that of formaldehyde — are limited elsewhere in Europe. In the U.S., Minnesota has banned in-state sales of children’s personal care products that contain the chemical.

Use of lead-based interior paints was banned in France, Belgium and Austria in 1909. Much of Europe followed suit before 1940. It took the U.S. until 1978 to make this move, even though health experts had, for decades, recognized the potentially acute — even deadly — and irreversible hazards of lead exposure.

These are but a few examples of chemical products allowed to be used in the U.S. in ways other countries have decided present unacceptable risks of harm to the environment or human health. How did this happen? Are American products less safe than others? Are Americans more at risk of exposure to hazardous chemicals than, say, Europeans?

Not surprisingly, the answers are complex and the bottom line, far from clear-cut. One thing that is evident, however, is that “the policy approach in the U.S. and Europe is dramatically different."

A key element of the European Union’s chemicals management and environmental protection policies — and one that clearly distinguishes the EU’s approach from that of the U.S. federal government — is what’s called the precautionary principle. This principle, in the words of the European Commission, “aims at ensuring a higher level of environmental protection through preventative” decision-making. In other words, it says that when there is substantial, credible evidence of danger to human or environmental health, protective action should be taken despite continuing scientific uncertainty.

In contrast, the U.S. federal government’s approach to chemicals management sets a very high bar for the proof of harm that must be demonstrated before regulatory action is taken.

This is true of the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act, the federal law that regulates chemicals used commercially in the U.S. The European law regulating chemicals in commerce, known as REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals), requires manufacturers to submit a full set of toxicity data to the European Chemical Agency before a chemical can be approved for use. U.S. federal law requires such information to be submitted for new chemicals, but leaves a huge gap in terms of what’s known about the environmental and health effects for chemicals already in use. Chemicals used in cosmetics or as food additives or pesticides are covered by other U.S. laws — but these laws, too, have high burdens for proof of harm and, like TSCA, do not incorporate a precautionary approach.

While FDA approval is required for food additives, the agency relies on studies performed by the companies seeking approval of chemicals they manufacture or want to use in making determinations about food additive safety. Natural Resources Defense Council senior scientist Maricel Maffini and NRDC senior attorney Tom Neltner “No other developed country that we know of has a similar system in which companies can decide the safety of chemicals put directly into food,” says Maffini. The two point to a number of food additives allowed in the U.S. that other countries have deemed unsafe.

Reliance on voluntary measures is a hallmark of the U.S. approach to chemical regulation. In many cases, when it comes to eliminating toxic chemicals from U.S. consumer products, manufacturers’ and retailers’ own policies — often driven by consumer demand or by regulations outside the U.S. or at the state and local level — are moving faster than U.S. federal policy.

Cosmetics regulations are more robust in the EU than here,” says Environmental Defense Fund health program director Sarah Vogel. U.S. regulators largely rely on industry information, she says. Industry performs copious testing, but current law does not require that cosmetic ingredients be free of certain adverse health effects before they go on the market. (FDA regulations, for example, do not specifically prohibit the use of carcinogens, mutagens or endocrine-disrupting chemicals.)

For the FDA to restrict a product or chemical ingredient from cosmetics or personal care products involves a typically long and drawn-out process. What it does more often is to issue advisories.

At the same time, built into the U.S. chemical regulatory system is a large deference to industry. Central to current U.S. policy are cost-benefit analyses with very high bars for proof of harm rather than a proof of safety for entry onto the market. Voluntary measures have moved many unsafe chemical products off store shelves and out of use, but our requirements for proof of harm and the American historical political aversion to precaution mean we often wait far longer than other countries to act.

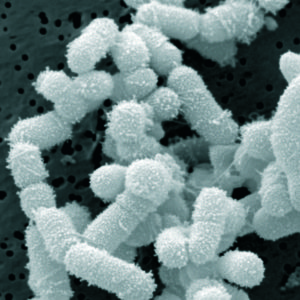

A big benefit to exercising - more microbial diversity, which means a healthier gut microbiome, which means better health. From Medscape:

A big benefit to exercising - more microbial diversity, which means a healthier gut microbiome, which means better health. From Medscape: It is now more than 69 weeks since I first successfully started using kimchi to treat the chronic sinusitis that had plagued me (and my family) for so many years. I originally reported on the Sinusitis Treatment on Dec. 6, 2013 (the method is described there) and followed up on Feb. 21, 2014.

It is now more than 69 weeks since I first successfully started using kimchi to treat the chronic sinusitis that had plagued me (and my family) for so many years. I originally reported on the Sinusitis Treatment on Dec. 6, 2013 (the method is described there) and followed up on Feb. 21, 2014.