This article by Dr. Thomas E. Finucane lays out nicely a paradigm shift in how to view uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) - as a case of dysbiosis (microbial community out of whack), and that antibiotics to kill bacteria are generally not needed or helpful. (He doesn't mention it, but the next step in his argument should be that probiotic or beneficial bacteria or other microbes may improve the microbial community and symptoms.) A main point of the article is that we now know the urinary tract is not sterile - instead diverse microbiota live there (the microbial community is the microbiome) including bacteria and viruses (the virome), and that these stable microbial communities are generally beneficial. Standard cultures do not pick up all the microbes living in the urinary tract.

This article by Dr. Thomas E. Finucane lays out nicely a paradigm shift in how to view uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) - as a case of dysbiosis (microbial community out of whack), and that antibiotics to kill bacteria are generally not needed or helpful. (He doesn't mention it, but the next step in his argument should be that probiotic or beneficial bacteria or other microbes may improve the microbial community and symptoms.) A main point of the article is that we now know the urinary tract is not sterile - instead diverse microbiota live there (the microbial community is the microbiome) including bacteria and viruses (the virome), and that these stable microbial communities are generally beneficial. Standard cultures do not pick up all the microbes living in the urinary tract.

He points out that: UTI symptoms are usually self-limited, of brief duration and only slightly shortened by antibiotic treatment; that cystitis rarely progresses to pyelonephritis (which does need antibiotic treatment); and that randomized trials show no reduction in the risk of progression to pyelonephritis with antibiotic treatment. He stresses the "generally benign (other than symptoms) nature of “symptomatic UTI” is suggested by the billions of persons around the world and over the years who have suffered “UTI” without access to antibiotics and have recovered fully". And that "urinary tract dysbiosis" may be a better description of what a woman is experiencing.

However, I would like to add that to a person experiencing an UTI, the pain does not at all feel "benign". So look at the posts on UTIs and treatments and perhaps try something like D- mannose or cranberry supplements, or both. From The American Journal of Medicine:

“Urinary tract infection” and the microbiome

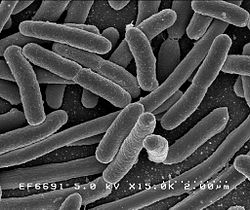

The current paradigm for managing uncomplicated “urinary tract infection” (“UTI”) is deeply flawed. “UTI” is ambiguously defined and, coupled with a belief that “bacteria are not normal inhabitants of the urinary tract, the diagnosis often leads to unnecessary, harmful antibiotic treatment. Although bacteriuria identified by standard clinical cultures (which we will call standard bacteriuria) is central to most definitions, more sensitive diagnostic tests now demonstrate that “urine is not sterile”2 and that standard bacteriuria represents a fraction of the diverse microbiota hosted by the urinary tract. Knowledge of this complex, generally beneficial microbiome deeply undermines the current paradigm, which relies on the findings of standard culture. By acknowledging this microbiome a successor paradigm will generate new questions about relationships among host, microbiome and antibiotic use and will almost surely show additional serious harms from antibiotic overtreatment.

This discussion concerns medically stable, non-pregnant adults with normal urinary tract structure and function. The role of antibiotics in patients with abnormalities of anatomy or physiology, such as spinal cord injury, urinary obstruction, or catheters, will require careful investigation. New insight into pyelonephritis and bacteremic bacteriuria is likely to develop.

The ambiguous definition of “UTI” seems to promote antibiotic overuse. In one common usage, “urinary tract infection is defined as microbial infiltration of the normally sterile urinary tract.” With this definition, asymptomatic bacteriuria is a “UTI” and is often treated, even in patient groups where strong evidence shows lack of benefit.4 A second common definition, “significant bacteriuria in a patient with symptoms or signs attributable to the urinary tract and no alternate source” seems more restrictive but does not define what symptoms or signs may be attributed to the urinary tract. This ambiguity creates opportunities for overtreatment....Antibiotic treatment of “UTI” often follows even though no data have shown these changes respond to treatment.

Canonically, “all symptomatic UTI should be treated” but actual benefit is limited. Hooton emphasizes that in acute uncomplicated cystitis “the primary goal of treatment is to ameliorate symptoms.” Foxman summarizes that symptoms are usually self-limited, of brief duration and only slightly shortened by antibiotic treatment; that cystitis rarely progresses to pyelonephritis; and that randomized trials show no reduction in the risk of progression to pyelonephritis with antibiotic treatment.7 The generally benign (other than symptoms) nature of “symptomatic UTI” is suggested by the billions of persons around the world and over the eons who have suffered “UTI” without access to antibiotics and have recovered fully.

With its various meanings, convenient diagnosis, long tradition, suggestive link to treatment and uncritical acceptance by clinicians, patients, families and insurers, “UTI” remains heavily embedded in practice, “one of the most common bacterial infections worldwide”. The paradigm provides tidy management for a patient with “UTI” who expects antibiotics. Further, the current paradigm does account for several findings. Standard bacteriuria is associated with pyuria, fever and dysuria, for example, and these often improve with treatment, as do a wide variety of findings seemingly unconnected with the urinary tract. Antibiotic treatment improves outcomes for asymptomatic pregnant women who have standard bacteriuria. Pyelonephritis and bacteremic bacteriuria probably arise in the urinary tract and do require antibiotic treatment.

To diagnose “UTI” and determine antibiotic sensitivity based on results of standard cultures, however, is to rely on familiar, accessible data and to ignore the dozens of bacterial species, as well as intracellular bacterial colonies and urinary virome known to reside in the urinary tract. Current discussions of symptomatic or asymptomatic bacteriuria or sterile urine are similarly problematic. To attribute delirium to standard bacteriuria seems unjustifiable, knowing that most or all people with or without delirium have bacteriuria. The current paradigm is defensible only if all pathogenic organisms are identified with standard cultures and all organisms more difficult to identify can be safely ignored.

We propose instead that urinary symptoms, bacteremia, pyelonephritis, and other recognizable disturbances of the urinary tract are the dysbiotic tip of a much larger iceberg of complex host-microbe interactions that are occurring out of sight of standard cultures. As expected in the era of the microbiome, stable bacterial communities are generally beneficial. For example, compared with the instillation of sterile saline, “bladder colonization with (the nonpathogenic) E. coli HU2117 safely reduces the risk of symptomatic urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury”.8 Of 699 young women with asymptomatic bacteriuria, half of whom were randomized to receive no antibiotic treatment, “treatment was associated with a higher rate of symptomatic UTI… (thus) asymptomatic bacteriuria … may play a protective role in preventing symptomatic recurrence” during 12-month follow-up.9

Costello and colleagues outline a broader paradigm shift in the general approach to infection; “transitioning clinical practice from the Body-as-Battleground to the Human-as-Habitat perspective will require rethinking how one manages the human body.”10 To help in this transition, mindful language will be important. We suggest that authors use “UTI” only within quotation marks and that clinicians use the bimanual “air quotes” gesture in discussions. This small, repetitive annotation is intended to disrupt the term’s complacent usage and encourage rethinking of how one manages bacteriuria. The term “urinary tract dysbiosis” may be useful for otherwise well patients with urinary tract symptoms.

“UTI” is an ill-defined, glibly overdiagnosed and overtreated “infection”. Current management ignores modern science. The associated antibiotic overuse causes serious harm to patient safety and to public health. Instead of the current-paradigm question, “Does this patient have a UTI?” the successor-paradigm question will be, “Does evidence show that antibiotic treatment is likely to benefit this patient?” Shifting the paradigm is an urgent matter.

A study found that a combination of cranberry supplement (120 mg cranberries, with a minimum proanthocyanidin content of 32mg), the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and vitamin C (750 mg) three times a day was enough to prevent the recurrence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) for the majority of women in this small (36 patient) study. At 6 months there was a 61% success rate. No side effects were reported.

A study found that a combination of cranberry supplement (120 mg cranberries, with a minimum proanthocyanidin content of 32mg), the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and vitamin C (750 mg) three times a day was enough to prevent the recurrence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) for the majority of women in this small (36 patient) study. At 6 months there was a 61% success rate. No side effects were reported. My last post was about a recent Medscape article discussing whether

My last post was about a recent Medscape article discussing whether  How does the medical profession currently view probiotics in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially recurrent infections? Answer: Only a few studies have been done, but what little is known is promising, which is good because traditional antibiotic treatment has problems (especially antibiotic resistance).

How does the medical profession currently view probiotics in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially recurrent infections? Answer: Only a few studies have been done, but what little is known is promising, which is good because traditional antibiotic treatment has problems (especially antibiotic resistance).