For years medicine has viewed cancer as a "malignant seed" and looked for ways to kill these seeds before they spread throughout the body (metastasis). This past week two provocative articles stresses that we should also look at the "environments" that the cancer cells grow in - that some environments in the person nourish and encourage the growth of cancer, while other environments suppress the growth of cancer and don't allow its spread.

For years medicine has viewed cancer as a "malignant seed" and looked for ways to kill these seeds before they spread throughout the body (metastasis). This past week two provocative articles stresses that we should also look at the "environments" that the cancer cells grow in - that some environments in the person nourish and encourage the growth of cancer, while other environments suppress the growth of cancer and don't allow its spread.

This is a very different approach to cancer, but it also makes sense. Studies find that small cancers can just sit there harmlessly or regress on their own - even breast and prostate cancers, but it raises the questions: Why? Why do they regress or are suppressed in some people, but grow malignantly in others? What is different about those people and their bodies?

Researchers are starting to do research along these lines - that is, looking at the environment that cancer may or may not grow in. Yesterday's post discussed amazing research showing that cancer tumors are continuously shedding cancer cells in a person's body, but only in some people do they actually take root and grow. It's as if some people have environments that encourage growth of cancer, while other people have environments that do not.

Today's article, besides discussing the micro-environment in which cancer grows, also discusses the role of inflammation in cancer and how things causing inflammation (e.g., smoking, inactivity, poor diet) are also associated with cancer. So some micro-environments are good for cancer, and some are not. Some of the research I've posted in the past has tried to see if influencing the person's environment with "lots of exercise and activity"(here and here), or vitamin D levels in the body, or a person's diet somehow prevents or keeps cancer in check. From Nautilus:

The Problem with the Mutation-Centric View of Cancer

To better understand and treat cancer, physicians need to stop oversimplifying its causes. Cancer results not solely from genetic mutations but by adapting to and thriving in micro-environments in the body. That’s the point of view of James DeGregori, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.... In our conversation, DeGregori expanded on how a renewed focus on micro-environments and Darwinian evolutionary pressures can benefit cancer research.

How should we study the origins of cancer? My lab has been researching the origins of cancers for the last 15 to 17 years. We’re trying to understand cancer from an evolutionary viewpoint, understanding how it evolves. A lot of people think about cancer from an evolutionary viewpoint. But what sets us apart is that we’ve really come to understand cancer by the context these cells find themselves in.

What’s an example of such a context? While other people will think about aging as the time for mutations to cause advantageous events [for cancer] in cells, we see aging as a very different process. It’s not about the time you get mutations—you get many mutations when you’re young. It’s the tissue environment for the cells that changes dramatically as we age. Those new tissue environments basically stimulate the evolution. So the evolution isn’t a process that’s limited by the mutation so much as a process that is limited by micro-environment changes.

Instead of just attacking the cancer, we should be altering the micro-environment to disfavor the cancer. What we’ve shown is that you could take the same oncogenic mutation and put it into young cells in a young environment and it’s not advantageous [for cancer]. It doesn’t cause expansions and it doesn’t cause the cancer. You make that same mutation in old tissue and it can be adaptive for cancer.

When we’re young, our tissues are relatively constant and well maintained. If you look at the tissues of a 20-year-old and a 35-year-old, or maybe even a 40-year-old, you wouldn’t notice much of a difference. It’s not like we age linearly. It’s only after 45 or 50 that we start to really go downhill. Then that downhill accelerates. As those changes happen, our tissues are no longer presenting that same environment to our cells. What I argue is that we evolve stem cells, or the cells that are continuously making our tissues, to be well adapted to the youthful environment and not to be well adapted to an aged environment.

I’ve been criticized as putting forward a straw man because, essentially, they don’t really talk about micro-environment. But to me that’s the whole point—there’s a major factor that should be considered, and I would say not just “should.” You can’t really model cancer without it and yet they’re not taking it into account. In other words, the difference between a smoker and a nonsmoker isn’t just that the smoker has more mutations. The difference is the smoker’s lung—and I’m sure you’ve seen pictures of the charred blackened lungs of a smoker—and that presents a completely different environment for cells with mutations.

How can your ideas change the way doctors treat cancer? Mostly we now target the cancer cells. That’s changing somewhat. Immune therapies are in some ways targeting the environment. It’s almost like a predator strategy. Instead of just attacking the cancer, we should be altering the micro-environment to disfavor the cancer. If you just attack the cancer, you immediately select for resistance, which is what they see in the clinic so often. You can get a person into remission, but it’s keeping them in remission that’s the hard part. Cancer that comes back is inevitably worse than the cancer you started with.

.... If we can understand what factor about a smoker’s lung, or an old person’s lung, leads to more cancer, then we could modulate that factor to basically prevent the cancers from occurring in the first place. If it’s inflammation, for all we know maybe there are even dietary interventions that will reduce inflammation in the lungs. All the things we know that are associated with cancer are also associated with increased inflammation. Everything we know that basically leads to longer, healthier lives, is known to modulate inflammation. Exercise reduces it. Good diet reduces it. Not smoking, not exposing yourself to too much sun.

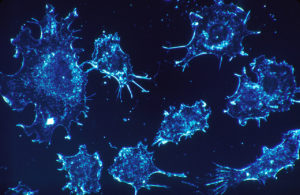

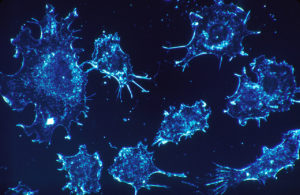

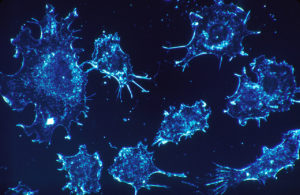

Cancer cells. Credit:Wikipedia, National Cancer Institute

Cancer cells. Credit:Wikipedia, National Cancer Institute

Another study has confirmed that if a person wants to have beneficial gut microbes that are associated with lower rates of chronic inflammation and many health conditions and diseases, then you need to eat a diet that nourishes the beneficial gut microbes. And once again, research finds that it is a plant based diet that does this.

Another study has confirmed that if a person wants to have beneficial gut microbes that are associated with lower rates of chronic inflammation and many health conditions and diseases, then you need to eat a diet that nourishes the beneficial gut microbes. And once again, research finds that it is a plant based diet that does this. On the other hand, a diet rich in processed foods and lots of meat (an animal derived diet), is associated with microbes linked to intestinal inflammation - thus an inflammatory diet . Also includes foods with high amounts of sugar and alcohol. This type of diet is low fiber and considered a Western diet.

On the other hand, a diet rich in processed foods and lots of meat (an animal derived diet), is associated with microbes linked to intestinal inflammation - thus an inflammatory diet . Also includes foods with high amounts of sugar and alcohol. This type of diet is low fiber and considered a Western diet.

Chronic low-grade inflammation in humans is drawing a lot of interest because it is linked to so many diseases (diabetes, cancer, etc). Key ways to lower this inflammation appear to be losing weight (if overweight), exercising, not smoking, and eating a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds (thus lots of

Chronic low-grade inflammation in humans is drawing a lot of interest because it is linked to so many diseases (diabetes, cancer, etc). Key ways to lower this inflammation appear to be losing weight (if overweight), exercising, not smoking, and eating a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds (thus lots of  For years medicine has viewed cancer as a "malignant seed" and looked for ways to kill these seeds before they spread throughout the body (metastasis). This past week two provocative articles stresses that we should also look at the "environments" that the cancer cells grow in - that some environments in the person nourish and encourage the growth of cancer, while other environments suppress the growth of cancer and don't allow its spread.

For years medicine has viewed cancer as a "malignant seed" and looked for ways to kill these seeds before they spread throughout the body (metastasis). This past week two provocative articles stresses that we should also look at the "environments" that the cancer cells grow in - that some environments in the person nourish and encourage the growth of cancer, while other environments suppress the growth of cancer and don't allow its spread. A

A