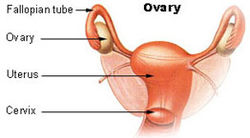

Another community of microbes found in humans in areas once thought to be sterile (without bacteria) - the ovaries and fallopian tubes in the female upper reproductive tract. And the interesting thing is that once again we see differences in the bacterial communities of areas with and without cancer (here the ovaries). From Science Daily:

Another community of microbes found in humans in areas once thought to be sterile (without bacteria) - the ovaries and fallopian tubes in the female upper reproductive tract. And the interesting thing is that once again we see differences in the bacterial communities of areas with and without cancer (here the ovaries). From Science Daily:

Bacteria found in female upper reproductive tract, once thought sterile

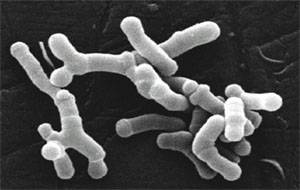

They're inside our gut, on the skin, and in the mouth. Thousands of different types of micro-organisms live in and on the body, playing helpful roles in digestion or in aiding the body's natural defense system. Now, scientists at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center have found tiny organisms living in the upper female reproductive tract, an environment they said was once thought to be sterile.

In a preliminary finding (abstract 5568) presented Monday, June 6, at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in Chicago, researchers revealed they have found bacteria in the ovaries and in the fallopian tubes. And with an additional finding that women with ovarian cancer have a different bacterial makeup, researchers are asking whether these tiny organisms could play a role in cancer development or progression.

To test whether there were bacteria in the upper female reproductive tract, researchers gathered samples from 25 women with and without cancer who were undergoing surgery to either have their uterus, fallopian tubes, or ovaries removed. The researchers then used genetic sequencing to determine what types of bacteria were present....Genetics-based approaches to identifying bacteria have made studies like theirs possible, Keku said, as some bacteria cannot be grown outside of the body in the laboratory.

From their analysis, the researchers found different types of bacteria in the fallopian tube and ovary. They also found differences in the types of bacteria in the upper reproductive tracts of women with and without epithelial ovarian cancer. Keku said the bacterial strains in the women with ovarian cancer were more pathogenic. The findings were borderline statistically significant, which the researchers said suggested a trend.

While they said it's too early to tell if the bacterial differences play a role in cancer development, researchers said their proof-of-concept study is a step needed to answer that question. Further studies are needed to determine if changes in the type of bacteria and other organisms in those regions come before the development of cancer.

Human female ovary and Fallopian tube. Credit: Wikipedia

Human female ovary and Fallopian tube. Credit: Wikipedia

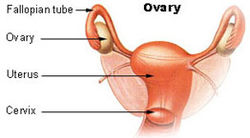

Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses

Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses  Try to avoid triclosan. Read labels (especially soaps, personal care, and household cleaning products) and avoid anything that says it contains triclosan, or is anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-microbial, or anti-odor. We easily absorb triclosan into our bodies, and it has been detected in our urine, blood, and breast milk. Among its many negative effects (e.g.,

Try to avoid triclosan. Read labels (especially soaps, personal care, and household cleaning products) and avoid anything that says it contains triclosan, or is anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-microbial, or anti-odor. We easily absorb triclosan into our bodies, and it has been detected in our urine, blood, and breast milk. Among its many negative effects (e.g.,  Dandruff is a very common scalp disorder that has occurred for centuries. A new study found that the most abundant bacteria on the scalp are Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, and that they have a reciprocal relationship with each other - when one is high, the other is low. When compared with a normal scalp, dandruff regions had decreased Propionibacterium and increased Staphylococcus. The researchers suggested that these findings suggest a new way to treat dandruff - to increase the Propionibacterium and decrease the Staphylococcus on the scalp. Stay tuned for possible future treatments using these findings. From Science Daily:

Dandruff is a very common scalp disorder that has occurred for centuries. A new study found that the most abundant bacteria on the scalp are Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, and that they have a reciprocal relationship with each other - when one is high, the other is low. When compared with a normal scalp, dandruff regions had decreased Propionibacterium and increased Staphylococcus. The researchers suggested that these findings suggest a new way to treat dandruff - to increase the Propionibacterium and decrease the Staphylococcus on the scalp. Stay tuned for possible future treatments using these findings. From Science Daily: Many probiotic manufacturers say that their product has all sorts of wonderful health benefits in people eating that particular probiotic, but is the evidence there? Finally, now there is a

Many probiotic manufacturers say that their product has all sorts of wonderful health benefits in people eating that particular probiotic, but is the evidence there? Finally, now there is a  E. coli bacteria in urine sample

E. coli bacteria in urine sample breast cancer cells

breast cancer cells prostate cancer cell

prostate cancer cell large intestine

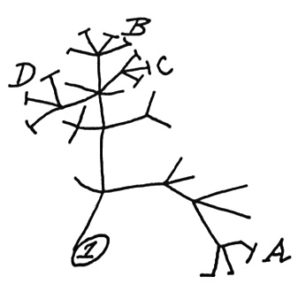

large intestine In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a simple tree of life (shown left) to illustrate the idea that all living things share a common ancestor. Ever since then, scientists have been adding names to the

In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a simple tree of life (shown left) to illustrate the idea that all living things share a common ancestor. Ever since then, scientists have been adding names to the

Another article commenting that

Another article commenting that  The eye has a normal community of microbes or eye microbiome, just like other body sites (i.e., the gut, the sinuses, the mouth). This community of bacteria is thought to offer resistance from invaders (such as pathogenic bacteria).

The eye has a normal community of microbes or eye microbiome, just like other body sites (i.e., the gut, the sinuses, the mouth). This community of bacteria is thought to offer resistance from invaders (such as pathogenic bacteria). The possibility of giving microbes in the future (whether bacteria, viruses, or fungi) to treat cancer is amazing. Of course big pharma is pursuing this line of research, which is called immunotherapy (stimulating the body's ability to fight tumors). The Bloomberg Business article discusses a number of big pharma companies entering the field and their main focus. The study in the journal Science finding that giving common beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum) to mice to slow down melanoma tumor growth is a first step. The researchers themselves said that the 2 common beneficial bacteria species exhibited anti-tumor activity in the mice and was as effective as an immunotherapy in controlling the growth of skin cancer. But note that the bacteria needed to be live. Stay tuned....

The possibility of giving microbes in the future (whether bacteria, viruses, or fungi) to treat cancer is amazing. Of course big pharma is pursuing this line of research, which is called immunotherapy (stimulating the body's ability to fight tumors). The Bloomberg Business article discusses a number of big pharma companies entering the field and their main focus. The study in the journal Science finding that giving common beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum) to mice to slow down melanoma tumor growth is a first step. The researchers themselves said that the 2 common beneficial bacteria species exhibited anti-tumor activity in the mice and was as effective as an immunotherapy in controlling the growth of skin cancer. But note that the bacteria needed to be live. Stay tuned....