New research found that one course of antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, amoxicillin or minocycline) had varying effects on the gut and saliva microbes, with ciprofloxacin having a negative and disruptive effect on gut microbiome diversity up to 12 months. While the microscopic communities living in the mouth rebound quickly, just one course of antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiome for months - with amoxicillin the least and ciprofloxacin the most (up to a year).The researchers stressed that for these reasons "antibiotics should only be used when really, really necessary. Even a single antibiotic treatment in healthy individuals contributes to the risk of resistance development and leads to long-lasting detrimental shifts in the gut microbiome."

New research found that one course of antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, amoxicillin or minocycline) had varying effects on the gut and saliva microbes, with ciprofloxacin having a negative and disruptive effect on gut microbiome diversity up to 12 months. While the microscopic communities living in the mouth rebound quickly, just one course of antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiome for months - with amoxicillin the least and ciprofloxacin the most (up to a year).The researchers stressed that for these reasons "antibiotics should only be used when really, really necessary. Even a single antibiotic treatment in healthy individuals contributes to the risk of resistance development and leads to long-lasting detrimental shifts in the gut microbiome."

The scary part is that Americans typically take many courses of antibiotics throughout life. And people with conditions such as chronic sinusitis typically take many more than average. From Medical Xpress:

One course of antibiotics can affect diversity of microorganisms in the gut

A single course of antibiotics has enough strength to disrupt the normal makeup of microorganisms in the gut for as long as a year, potentially leading to antibiotic resistance, European researchers reported this week in mBio, an online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology. In a study of 66 healthy adults prescribed different antibiotics, the drugs were found to enrich genes associated with antibiotic resistance and to severely affect microbial diversity in the gut for months after exposure. By contrast, microorganisms in the saliva showed signs of recovery in as little as few weeks.

The microorganisms in study participants' feces were severely affected by most antibiotics for months, said lead study author Egija Zaura, PhD, an associate professor in oral microbial ecology at the Academic Centre for Dentistry in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. In particular, researchers saw a decline in the abundance of health-associated species that produce butyrate, a substance that inhibits inflammation, cancer formation and stress in the gut.

"My message would be that antibiotics should only be used when really, really necessary," Zaura said. "Even a single antibiotic treatment in healthy individuals contributes to the risk of resistance development and leads to long-lasting detrimental shifts in the gut microbiome."

It's not clear why the oral cavity returns to normal sooner than the gut, Zaura said, but it could be because the gut is exposed to a longer period of antibiotics. Another possibility, she said, is that the oral cavity is intrinsically more resilient toward stress because it is exposed to different stressors every day.

The investigators enrolled healthy adult volunteers from the United Kingdom and Sweden. Participants were randomly assigned to receive a full course of one of four antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, amoxicillin or minocycline) or a placebo. The researchers, who did not know which medication participants took, collected fecal and saliva samples from the participants at the start of the study; immediately after taking the study drugs; and one, two, four and 12 months after finishing the medications....

Researchers found that participants from the United Kingdom started the study with more antibiotic resistance than did the participants from Sweden, which could result from cultural differences. There has been a significant decline in antibiotic use in Sweden over the last two decades, Zaura said.

In addition, fecal microbiome diversity was significantly reduced for up to four months in participants taking clindamycin and up to 12 months in those taking ciprofloxacin, though those drugs only altered the oral cavity microbiome up to one week after drug exposure. Exposure to amoxicillin had no significant effect on microbiome diversity in either the gut or oral cavity but was associated with the greatest number of antibiotic-resistant genes.

Gut bacteria. Credit: Med. Mic. Sciences Cardiff Univ, Wellcome Images

Gut bacteria. Credit: Med. Mic. Sciences Cardiff Univ, Wellcome Images

A recent study using mice, and following them for 4 generations, has implications for Americans who typically eat a low-fiber diet (average of 15 grams daily). Note that current dietary guidelines recommend that women should eat around 25 grams and men 38 grams daily of fiber. The researchers found that low-fiber diets not only deplete the complex microbial ecosystems residing in the gut, but can cause an irreversible loss of diversity within those ecosystems in as few as three or four generations.

A recent study using mice, and following them for 4 generations, has implications for Americans who typically eat a low-fiber diet (average of 15 grams daily). Note that current dietary guidelines recommend that women should eat around 25 grams and men 38 grams daily of fiber. The researchers found that low-fiber diets not only deplete the complex microbial ecosystems residing in the gut, but can cause an irreversible loss of diversity within those ecosystems in as few as three or four generations.

The following article is interesting because it describes how microbes are high up in the sky riding air currents and winds to circle the earth, and eventually drop down somewhere. This is one way

The following article is interesting because it describes how microbes are high up in the sky riding air currents and winds to circle the earth, and eventually drop down somewhere. This is one way  New research that found that microbial communities vary between the sinuses in a person with chronic sinusitis. This is a result that many sinusitis sufferers already suspect based on their sinusitis symptoms. The researchers also found that bacterial communities in the sinuses vary between people with chronic sinusitis. It is frustrating though for me to read study after study where the researchers focus on describing the types of bacteria found in chronic sinusitis sufferers (and then just saying that the sinus

New research that found that microbial communities vary between the sinuses in a person with chronic sinusitis. This is a result that many sinusitis sufferers already suspect based on their sinusitis symptoms. The researchers also found that bacterial communities in the sinuses vary between people with chronic sinusitis. It is frustrating though for me to read study after study where the researchers focus on describing the types of bacteria found in chronic sinusitis sufferers (and then just saying that the sinus  Could the bacteria described in this research be another probiotic or beneficial bacteria (besides Lactobacillus sakei) that helps protect against sinusitis? New research found that the harmless bacteria Corynebacterium accolens is "overrepresented" in children free of Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) - which commonly colonizes in children's noses (and that can live harmlessly as part of a healthy microbiome), but it is also an important infectious agent. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of pneumonia, septicemia, meningitis, otitis media (ear infections), and sinusitis in children and adults worldwide.

Could the bacteria described in this research be another probiotic or beneficial bacteria (besides Lactobacillus sakei) that helps protect against sinusitis? New research found that the harmless bacteria Corynebacterium accolens is "overrepresented" in children free of Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) - which commonly colonizes in children's noses (and that can live harmlessly as part of a healthy microbiome), but it is also an important infectious agent. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of pneumonia, septicemia, meningitis, otitis media (ear infections), and sinusitis in children and adults worldwide. Research found that postmenopausal women with periodontal disease (gum disease) were more likely to develop breast cancer than women who did not have the chronic inflammatory disease. And it's a bigger risk among those who currently smoke or quit smoking within the last 20 years. The interesting part is the fact that periodontal disease is a bacterial disease and that it results in inflammation. An earlier

Research found that postmenopausal women with periodontal disease (gum disease) were more likely to develop breast cancer than women who did not have the chronic inflammatory disease. And it's a bigger risk among those who currently smoke or quit smoking within the last 20 years. The interesting part is the fact that periodontal disease is a bacterial disease and that it results in inflammation. An earlier  Interesting, but in some ways horrifying - the hidden world of microbes teeming around us. With new techniques such as genetic sequencing we now know that at least a couple of thousand different species live in our water pipes in

Interesting, but in some ways horrifying - the hidden world of microbes teeming around us. With new techniques such as genetic sequencing we now know that at least a couple of thousand different species live in our water pipes in

The mother is an important source of the first microbiome for infants by "seeding" the baby's microbiome - from the

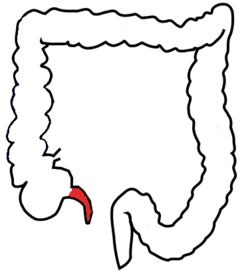

The mother is an important source of the first microbiome for infants by "seeding" the baby's microbiome - from the  This new study gives further support for the role of the appendix as a "natural reservoir for 'good' bacteria". The researchers found that a network of immune cells (innate lymphoid cells or ILCs) safeguard the appendix during a bacterial attack and help the appendix "reseed" the gut microbiome. They also said that a person's diet, such as the proteins in leafy green vegetables, could help produce ILCs. Note that while it is thought that this applies to humans, the research was done on mice. From Medical Xpress:

This new study gives further support for the role of the appendix as a "natural reservoir for 'good' bacteria". The researchers found that a network of immune cells (innate lymphoid cells or ILCs) safeguard the appendix during a bacterial attack and help the appendix "reseed" the gut microbiome. They also said that a person's diet, such as the proteins in leafy green vegetables, could help produce ILCs. Note that while it is thought that this applies to humans, the research was done on mice. From Medical Xpress:

New research found that one course of

New research found that one course of