I posted about this amazing research while it was still ongoing (Jan. 16, 2015), but now a study has been published. The small well-done pilot study looked at the microbiome (microbial communities) and microbial differences between different groups of infants during the first 30 days of life. They found significant differences in the bacteria of C-section infants (not exposed to their mother's vaginal fluid in the birth canal) compared to C-section infants who were swabbed with a gauze pad right after birth with their mother's vaginal fluids. They found that the microbiota (community of microbes) is partially restored in the swabbed C-section infants and more similar to that of vaginally delivered infants (who were exposed to the maternal bacteria naturally in the birth canal). They found that the procedure restored some bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bacteroides, which were nearly absent in the skin and anal samples of non-swabbed C-section babies.

I posted about this amazing research while it was still ongoing (Jan. 16, 2015), but now a study has been published. The small well-done pilot study looked at the microbiome (microbial communities) and microbial differences between different groups of infants during the first 30 days of life. They found significant differences in the bacteria of C-section infants (not exposed to their mother's vaginal fluid in the birth canal) compared to C-section infants who were swabbed with a gauze pad right after birth with their mother's vaginal fluids. They found that the microbiota (community of microbes) is partially restored in the swabbed C-section infants and more similar to that of vaginally delivered infants (who were exposed to the maternal bacteria naturally in the birth canal). They found that the procedure restored some bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bacteroides, which were nearly absent in the skin and anal samples of non-swabbed C-section babies.

In the C-section group, four mothers who were free of infections that might harm the babies, incubated a sterile gauze in their vaginas for one hour before the operation (C-section). Then, within two minutes of birth, the babies were swabbed with the gauze first over their mouths, then their faces, and then the rest of their bodies. These results are important because it is thought that microbiome differences (depending on method of birth) are long-lasting (with higher incidence of some health problems later in life with C-sections), and because the baby's early microbiome helps educate the baby's developing immune system.

Rob Knight (a leading microbiologist and one of the researchers) pointed out that the study "provides the proof-of-concept that microbiome modification early in life is possible." Now we need to see if these microbial differences persist over time and if it makes a health difference. From Science Daily:

Vaginal microbes can be partially restored to c-section babies

In a small pilot study, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai determined that a simple swab to transfer vaginal microbes from a mother to her C-section-delivered newborn can alter the baby's microbial makeup (microbiome) in a way that more closely resembles the microbiome of a vaginally delivered baby.

Babies delivered by C-section differ from babies delivered vaginally in the makeup of the microbes that live in and on their bodies. These early microbiomes help educate the baby's developing immune system. Previous research suggests a link between C-section delivery and increased subsequent risk of obesity, asthma, allergies, atopic disease and other immune deficiencies. Many of these diseases have also been linked to the microbiome, though the role a newborn's microbiome plays in current or long-term health is not yet well-understood....Other research suggests that microbiome differences between vaginal and C-section babies can persist for years."

In the study, the researchers collected samples from 18 infants and their mothers, including seven born vaginally and 11 delivered by scheduled C-section. Of the C-section-delivered babies, four were exposed to their mothers' vaginal fluids at birth as part of this study. To do this, sterile gauze was incubated in the mothers' vaginas for one hour before the C-section. Within two minutes of their birth, the babies delivered by C-section were swabbed with the gauze starting with the mouth, then the face and the rest of the body.

Six times over the first month after birth, the researchers collected a total of 1,519 anal, oral and skin samples from the mothers and infants. Knight's team then used a gene sequencing technique to map the types and relative quantities of bacterial species present at each body site.

Here's what they found: the microbiomes of the four C-section-delivered infants exposed to vaginal fluids more closely resembled those of vaginally delivered infants than unexposed C-section-delivered infants, though the difference was more distinct in their oral and skin samples than in their anal samples. This partial microbial restoration could be due to the fact that the infants received only one surface application of maternal vaginal fluids, Knight said.

Yet the oral and skin microbiome differences between C-section-delivered infants who received the microbial transfer and those who did not was still noticeable one month after birth. The results were not due to diet differences, as all of the infants received breast milk either exclusively or supplemented with formula during the first month of life. In addition, consistent with previous studies, the babies' microbiome profiles did not correlate with the amount of breast milk they received.

"The present work is a pilot study -- we need substantially more children and a longer follow-up period to connect the procedure to health effects," said Knight...."This study points the way to how we would do that, and provides the proof-of-concept that microbiome modification early in life is possible. In fact, we already have more than 10,000 additional samples collected as part of this study that still await analysis."

This is an issue that a lot of women I've known over the years have wondered about: if a woman gets pregnant while on birth control pills (oral contraceptives) - and many women do - does it mean higher rates of birth defects? This study says NO to higher rates of

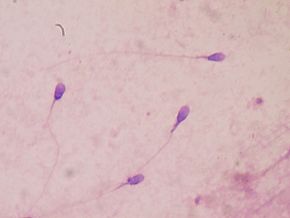

This is an issue that a lot of women I've known over the years have wondered about: if a woman gets pregnant while on birth control pills (oral contraceptives) - and many women do - does it mean higher rates of birth defects? This study says NO to higher rates of  More and more negative news about phthalates: men with greater exposure to DEHP (a phthalate) have lower

More and more negative news about phthalates: men with greater exposure to DEHP (a phthalate) have lower  A large study found that using antidepressants during the second or third trimester of pregnancy increases the risk that the child will have autism by 87%, especially if the mother takes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). A drawback was that the study looked at associations rather than actual cause (which would have meant randomly assigning women to either treatment or no treatment - which is unethical). From Medical Xpress:

A large study found that using antidepressants during the second or third trimester of pregnancy increases the risk that the child will have autism by 87%, especially if the mother takes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). A drawback was that the study looked at associations rather than actual cause (which would have meant randomly assigning women to either treatment or no treatment - which is unethical). From Medical Xpress: Recent research looked at environmental causes of male infertility, specifically endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Recent research looked at environmental causes of male infertility, specifically endocrine-disrupting chemicals. An interesting Canadian study that followed young children for 3 years found that young infants may be more likely to develop allergic

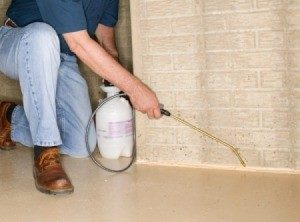

An interesting Canadian study that followed young children for 3 years found that young infants may be more likely to develop allergic  Children exposed to insecticides (pesticides) at home have an increased risk of developing leukemia or lymphoma, a new review finds.The analysis, of 16 studies done since the 1990s, found that children exposed to indoor insecticides had an elevated risk of developing the blood cancers. There was also a weaker link between exposure to weed killers and the risk of leukemia.

Children exposed to insecticides (pesticides) at home have an increased risk of developing leukemia or lymphoma, a new review finds.The analysis, of 16 studies done since the 1990s, found that children exposed to indoor insecticides had an elevated risk of developing the blood cancers. There was also a weaker link between exposure to weed killers and the risk of leukemia. Disturbing results from a study looking at data from over 1 million women enrolled in Medicaid before pregnancy from 2000 to 2007. More than four of five (82.5%) pregnant women were prescribed at least one medication, and 42.0% were prescribed a drug that is potentially harmful to the developing fetus.From Medscape:

Disturbing results from a study looking at data from over 1 million women enrolled in Medicaid before pregnancy from 2000 to 2007. More than four of five (82.5%) pregnant women were prescribed at least one medication, and 42.0% were prescribed a drug that is potentially harmful to the developing fetus.From Medscape: Several recent studies have found that constant exposure to high levels of air pollution has negative effects on the brain. The

Several recent studies have found that constant exposure to high levels of air pollution has negative effects on the brain. The