Another study finding more benefits of exercise was recently published in the journal Neurology. The study by researchers at Duke University found that in older adults who were already experiencing cognitive (thinking) problems, but did not have dementia - that after just 6 months of exercise they showed improvements in thinking. What were their original thinking problems? The individuals had difficulty concentrating, making decisions, or remembering, but it was not severe enough to be diagnosed as dementia. However, these persons were considered at risk for progressing to dementia.

Another study finding more benefits of exercise was recently published in the journal Neurology. The study by researchers at Duke University found that in older adults who were already experiencing cognitive (thinking) problems, but did not have dementia - that after just 6 months of exercise they showed improvements in thinking. What were their original thinking problems? The individuals had difficulty concentrating, making decisions, or remembering, but it was not severe enough to be diagnosed as dementia. However, these persons were considered at risk for progressing to dementia.

The 160 individuals in the study were 55 years or older (mean age 65), mainly women, evenly divided between whites and minorities, were sedentary (didn't exercise), and had heart (cardiovascular) disease or were at risk for heart disease. They were randomly assigned to one of 4 groups: 1) aerobic exercise (with no dietary changes), 2) DASH diet (with no exercise), 3) DASH diet plus exercise, and 4) the control group, who had no dietary or exercise changes - they just received some educational phone calls. The study lasted 6 months, and there were no drop outs.

In the study, the aerobic exercises were done 3 times per week: 10 minutes of warm up exercises followed by 35 minutes of continuous walking or stationary cycling. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension or DASH diet is a heart healthy diet that emphasizes eating fruits, vegetables, whole grains, as well as fish, poultry, beans, and nuts. It stresses lowering the intake of salt (sodium), sweets, sugar sweetened beverages, and fatty foods (both trans fats and saturated fats). [Note that in many ways it's similar to the Mediterranean diet with its emphasis on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, and lowering intake of meat. Studies find cognitive benefits from the Mediterranean diet.]

The six months of exercising improved thinking skills called executive function - in both the exercise alone or exercise + DASH diet group. The largest improvements were in the exercise + DASH diet group (as compared to the control group, which actually showed decline in functioning). Executive function is a person's ability to regulate their own behavior, pay attention, organize and achieve goals, and was measured in this study with a group of cognitive tests (a "standard battery of neurocognitive tests"). These executive function improvements did not occur in the DASH diet alone group or the control group. The study found no improvement in memory or language fluency in any of the groups. The exercise alone, DASH diet alone, and the combined exercise and DASH group had other health benefits by the end of the study, for example they lowered their risk factors for heart disease. Other improvements: the exercise groups had improvements in insulin levels, and the DASH groups decreased their intake of blood pressure medicines.

To illustrate how amazing these results are: at the start of the study (baseline) all participants scored as if they were in their early 90s on cognitive tests - as if they were on average about 28 years older than their actual chronological age! Then at the end of 6 months, the persons in the exercise + DASH diet showed an improvement of almost 9 years on the tests. In contrast, the control group showed an approximately 6 month worsening performance. When researchers looked at physical markers of the exercisers, they found that physical improvements and improvements in heart disease risk factors (e.g. losing weight, lowering blood pressure) were correlated with executive functioning improvements.

Other studies have found related findings, such as higher physical activity and a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower levels of dementia. The researchers point out that there is growing evidence that combining several lifestyle factors (e.g., exercise, not smoking, a healthy diet, lowering salt intake) and not just exercise alone, has the best results for better cognitive functioning among older adults. Bottom line: eat a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, seeds, nuts and get exercise. Walking briskly, gardening, housework, walking up stairs - it all counts. ...continue reading "Can Exercise and Dietary Changes Help Older Adults With Thinking Problems?"

The results of a

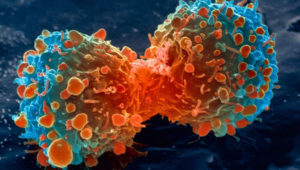

The results of a  For those who need convincing that lifestyle can contribute to development of cancer or its prevention, new medical research has once again supported the importance of lifestyle choices.

For those who need convincing that lifestyle can contribute to development of cancer or its prevention, new medical research has once again supported the importance of lifestyle choices.