Yes, of course this makes sense!.... Many rounds of antibiotics have an effect not just in one area of the body, but kill off both good and bad bacteria in many areas of the human body. The researchers in this study found that taking antibiotics for a reason OTHER THAN SINUSITIS was associated with an increased risk of developing chronic sinusitis (as compared to those people not receiving antibiotics).

Yes, of course this makes sense!.... Many rounds of antibiotics have an effect not just in one area of the body, but kill off both good and bad bacteria in many areas of the human body. The researchers in this study found that taking antibiotics for a reason OTHER THAN SINUSITIS was associated with an increased risk of developing chronic sinusitis (as compared to those people not receiving antibiotics).

Use of antibiotics more than doubles the odds of developing chronic sinusitis without nasal polyps. And this effect lasted for at least 2 years.

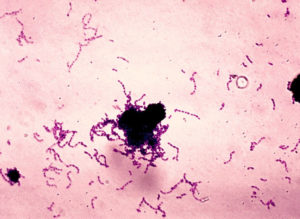

Other research has already associated antibiotic use with "decreased microbial diversity" in our microbiome and with "opportunistic infections" such as Candida albicans and Clostridium difficile. Diseases such as Crohn's disease and diabetes are also linked to antibiotic use. In other words, when there is a disturbance in the microbiome (e.g.from antibiotics) and the community of microbes becomes "out of whack", then pathogenic bacteria are "enriched" (increase) and can dominate.

This study lumped together chronic sinusitis without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) and chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), but when the 2 groups are separated out, then antibiotic use was mainly associated with chronic sinusitis without polyps. It appeared that antibiotic exposure did not significantly impact the odds of developing chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps.

The researchers write: "This effect was primarily driven by the CRSsNP subgroup, which also supports the evolving concept of CRSwNP (chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps) as a disease of primary inflammation rather than infection. Despite this, we elected to analyze the CRS (chronic rhinosinusitis) group as a whole because the precise relationship between CRS with and without nasal polyps remains incompletely understood, and it is possible that a proportion of the CRSsNP patients could go on to develop nasal polyps over time."

Which makes me wonder, will giving beneficial bacteria (such as Lactobacillus sakei) to those who have chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps show the same improvement in symptoms as those people without nasal polyps? Or do 2 treatments have to occur at once: something to lower the inflammation (which may be the reason for the nasal polyps) and also beneficial microbes to treat the bacterial imbalance of sinusitis? We just don't know yet. Note that CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis (commonly called chronic sinusitis). Research by A.Z. Maxfield et al from The Laryngoscope :

General antibiotic exposure is associated with increased risk of developing chronic rhinosinusitis

Antibiotic use and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) have been independently associated with microbiome diversity depletion and opportunistic infections. This study was undertaken to investigate whether antibiotic use may be an unrecognized risk factor for developing CRS. Case-control study of 1,162 patients referred to a tertiary sinus center for a range of sinonasal disorders.

Patients diagnosed with CRS according to established consensus criteria (n = 410) were assigned to the case group (273 without nasal polyps [CRSsNP], 137 with nasal polyps [CRSwNP]). Patients with all other diagnoses (n = 752) were assigned to the control group. Chronic rhinosinusitis disease severity was determined using a validated quality of life (QOL) instrument. The class, diagnosis, and timing of previous nonsinusitis-related antibiotic exposures were recorded.

Antibiotic use significantly increased the odds of developing CRSsNP as compared to nonusers. Antibiotic exposure was significantly associated with worse CRS QOL {Quality of Life} scores over at least the subsequent 2 years. These findings were confirmed by the administrative data review. Use of antibiotics more than doubles the odds of developing CRSsNP and is associated with a worse QOL for at least 2 years following exposure. These findings expose an unrecognized and concerning consequence of general antibiotic use.

Antibiotic use and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) have been independently associated with microbiome diversity depletion and opportunistic infections. This study was undertaken to investigate whether antibiotic use may be an unrecognized risk factor for developing CRS.....Antibiotics have also been associated with significant adverse side effects. It has long been recognized that antibiotic use may lead to increased susceptibility to secondary mucosal infections from pathogens including Candida albicans and Clostridium difficile. Recent studies on the concept of mucosal microbial dysbiosis have suggested that these infections arise as a result of antibiotic induced depletion of the diverse commensal microbial assemblage, which enables the proliferation of pathogenic species.

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is defined....as having greater than 12 weeks of sinonasal symptoms, along with at least one objective measure of infection or inflammation by nasal endoscopy or radiographic imaging....However the distinct lack of long-term disease resolution following antimicrobial therapy and in some cases surgery, suggests that additional factors are likely involved. Through these studies, CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has been recognized as an inflammatory subtype characterized by eosinophilic inflammation and a T-helper cell type 2 immunologic profile. Although CRSwNP lacks the features of a classic infectious process, the precise role of bacteria and their byproducts in the promotion of nasal polyp-related inflammation remains unclear.

Recent findings from culture independent investigations of the sinonasal microbiome have offered new insights into the pathogenesis of CRS. These studies have suggested that a decreased microbial diversity exists in CRS patients as compared to healthy controls with a selective enrichment of pathogenic species. Furthermore, some studies have shown that antibiotic exposure may be a risk factor associated with this loss of biodiversity, echoing the findings seen in postantibiotic C. difficile infections. Although systemic antibiotics have long been a mainstay of therapy for CRS, these findings lead inexorably to the paradoxical hypothesis that antibiotic exposure may, in fact, promote its onset.

We performed a....case control study of 1,574 patients referred to the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Sinus Center in 2014 with symptoms of presumed sinonasal disease.... Inclusion criteria included all antibotic naive patients, and all antibiotic exposed patients for whom antibiotic use was for nonsinonasal-related infections. Among the antibiotic exposed group, only patients who used antibiotics for nonsinonasal-related infections prior to the onset of symptoms of CRS (within the case group) were enrolled in the study.....The case group was further substratified into CRS patients without nasal polyps (CRSsNP, n =273) and with nasal polyps (CRSwNP, n =137) based on the presence of nasal polyps on sinonasal endoscopy.

Among the case patients, 56.34% reported a previous nonsinus-related antibiotic exposure as compared to 42.02% of control patients. Antibiotic use significantly increased the odds of developing both CRSsNP and any form of CRS as compared to nonusers. This odds ratio was similar even when excluding patients who were treated for upper aerodigestive infections. In contrast, antibiotic exposure did not significantly impact the odds of developing CRSwNP. The percent of patients with any form of CRS and CRSsNP only, which was attributable to a previous exposure to antibiotics, was 24.69% and 33.70%, respectively. In both the case and control groups, the most common class of antibiotic patients received was a penicillin (52.63% vs. 45.77%), and the most common reported reason for antibiotic prescription was the diagnosis of pharyngitis(18.06% vs. 16.67%).

Among the CRS patients (i.e., case group), the use of antibiotics was significantly associated with worse QOL scores as compared to antibiotic-naıve CRS patients. The effect on QOL was enduring because patients who used antibiotics at least 2 years prior to the development of CRS (36.81%) had similar disease severity scores as compared to those with more recent exposures. There was no significant difference in QOL score among patients using different antibiotic classes and among patients with different underlying reasons for antibiotic use.

The human microbiome project has provided new insights into the distribution and abundance of bacterial species in both health and disease. Opportunistic pathogens, as defined by the pathosystems resource integration center, were found nearly ubiquitously in the nares of healthy subjects, albeit at relatively low abundance. Additional studies of the normal nasal cavity found an inverse correlation between the prevalence of Firmicutes such as S. aureus and benign commensal organisms, suggesting a homestatic antagonism between potential pathogens and the remainder of the healthy microbial assemblage. Extrapolation of this concept would therefore predict that events resulting in a perturbation or loss of the commensal microbial community would enable proliferation of pathogenic species, resulting in the disease phenotype. This prediction has borne out in several studies of the sinonasal microbiome in patients with CRS. Feazel et al. found a decreased number of bacterial types and an overabundance of S. aureus among CRS patients as compared to controls. Antibiotic exposure was one of the most significant clinical factors driving this effect. Similar findings were published by Choi et al. and Abreu et al.... Although literature regarding the sinonasal microbiome in health and disease remains nascent, it has provided some limited clues that antibiotics may lead to a reduction of sinonasal microbial biodiversity, which in turn may be a significant feature of CRS.

Our results demonstrate that exposure to antibiotics is a significant risk factor for the development of CRS and accounts for approximately 25% of the disease burden in our study population. These findings harmonize with the predictions of the nascent literature on the sinonasal microbiome. This effect was primarily driven by the CRSsNP subgroup, which also supports the evolving concept of CRSwNP as a disease of primary inflammation rather than infection. Despite this, we elected to analyze the CRS group as a whole because the precise relationship between CRS with and without nasal polyps remains incompletely understood, and it is possible that a proportion of the CRSsNP patients could go on to develop nasal polyps over time.....

One unexpected outcome of our study was that a large percentage of exposures preceeded the onset of the diagnosis of sinusitis by more than 2 years. This indicates that, regardless of the mechanism, the sequelae of antibiotic use may endure much longer then previously thought....The impact of antibiotics on promoting bacterial resistance, and the development of mucosal infections from pathogens such as C. difficile and C. albicans, has been well established. This study demonstrates that antibiotics also significantly increase the risk of developing CRS, an effect that is driven primarily by CRS patients who do not have nasal polyps. Furthermore, premorbid antibiotic use could account for approximately 25% of our patients who developed CRS, and exposure conferred a worse disease-specific quality of life.

Yikes! Another study showing effects from antibiotic use - this time a higher incidence of food allergies in children who took antibiotics in the first year of life. Especially multiple courses of antibiotics, with the strongest association among children receiving cephalosporin and sulfonamide antibiotics. Antibiotics can be life-saving, but there can also be unintended consequences.

Yikes! Another study showing effects from antibiotic use - this time a higher incidence of food allergies in children who took antibiotics in the first year of life. Especially multiple courses of antibiotics, with the strongest association among children receiving cephalosporin and sulfonamide antibiotics. Antibiotics can be life-saving, but there can also be unintended consequences.

A

A  Yes, of course this makes sense!.... Many rounds of antibiotics have an effect not just in one area of the body, but kill off both good and bad bacteria in many areas of the human body. The researchers in this study found that taking antibiotics for a reason OTHER THAN SINUSITIS was associated with an increased risk of developing chronic sinusitis (as compared to those people not receiving antibiotics).

Yes, of course this makes sense!.... Many rounds of antibiotics have an effect not just in one area of the body, but kill off both good and bad bacteria in many areas of the human body. The researchers in this study found that taking antibiotics for a reason OTHER THAN SINUSITIS was associated with an increased risk of developing chronic sinusitis (as compared to those people not receiving antibiotics). Earlier posts discussed research that showed that farm and animal (pets such as dogs) exposures in the first year of life is protective against allergies and asthma (lowers the risk of developing them).

Earlier posts discussed research that showed that farm and animal (pets such as dogs) exposures in the first year of life is protective against allergies and asthma (lowers the risk of developing them).

Research shows that Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria that is a main cause of tooth decay or dental caries, is passed from mother to child, and also between nonrelative children. Any interaction that involves

Research shows that Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria that is a main cause of tooth decay or dental caries, is passed from mother to child, and also between nonrelative children. Any interaction that involves

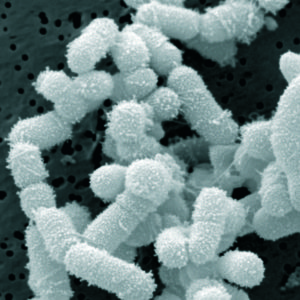

Another view of type 2 diabetes - that the gut microbiome is involved, specifically two gut bacteria: Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus. View them as the bad guys. The researchers point out "... the majority of overweight and obese individuals are insulin resistant and it is well known that dietary shifts to less calorie-dense eating and increased daily intake of any kind of vegetables and less intake of food rich in animal fat tend to normalize imbalances of gut microbiota and simultaneously improve insulin sensitivity of the host." In other words, eat more vegetables and fewer calories (if you're overweight or obese) to improve the gut microbes. This is similar to yesterday's post of

Another view of type 2 diabetes - that the gut microbiome is involved, specifically two gut bacteria: Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus. View them as the bad guys. The researchers point out "... the majority of overweight and obese individuals are insulin resistant and it is well known that dietary shifts to less calorie-dense eating and increased daily intake of any kind of vegetables and less intake of food rich in animal fat tend to normalize imbalances of gut microbiota and simultaneously improve insulin sensitivity of the host." In other words, eat more vegetables and fewer calories (if you're overweight or obese) to improve the gut microbes. This is similar to yesterday's post of  sinusitis

sinusitis