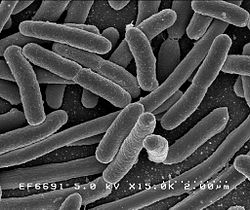

Very exciting research IF it pans out - the idea of treating (some) cancers with probiotics (beneficial bacteria). This study was done on mice, and some mice started the probiotic mixture one week before they gave the mice the liver cancer, so...more limitations there. But the idea is so tantalizing and wonderful... And what was in the mixture of bacteria (called probiotic Prohep) that the mice ate that had beneficial results of shrinking liver tumors? The probiotic Prohep is composed of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN), and heat inactivated VSL#3 (1:1:1). VSL#3 contains: Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Note that Lactobacillus rhamnosus and some of the others are already found in many probiotic mixtures. From Medical Xpress:

Very exciting research IF it pans out - the idea of treating (some) cancers with probiotics (beneficial bacteria). This study was done on mice, and some mice started the probiotic mixture one week before they gave the mice the liver cancer, so...more limitations there. But the idea is so tantalizing and wonderful... And what was in the mixture of bacteria (called probiotic Prohep) that the mice ate that had beneficial results of shrinking liver tumors? The probiotic Prohep is composed of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN), and heat inactivated VSL#3 (1:1:1). VSL#3 contains: Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Note that Lactobacillus rhamnosus and some of the others are already found in many probiotic mixtures. From Medical Xpress:

Probiotics dramatically modulate liver cancer growth in mice

Medical research over the last decade has revealed the effects of the gut microbiome across a range of health markers including inflammation, immune response, metabolic function and weight....Previous studies have demonstrated the beneficial role of probiotics in reducing gastrointestinal inflammation and preventing colorectal cancer, but a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explored their immunomodulatory effects on extraintestinal tumors: specifically, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC is the most common type of liver cancer, and though it is relatively uncommon in the United States, it's the second-most deadly type of cancer worldwide and is particularly prevalent in regions with high rates of hepatitis.

The researchers designed a study in a mouse model of HCC that quantified the immunological effects of a novel probiotic formulation called Prohep. They fed the mice Prohep for a week prior to tumor inoculation, and they observed a 40 percent reduction of tumor weight and size compared with control animals. Further, they established that the beneficial effects of the probiotics were closely related to the abundance of beneficial bacteria promoted by Prohep. These bacteria produce anti-inflammatory metabolites, which regulated pro-inflammatory immune cell populations via crosstalk between the gut and the liver tumor.

Among their findings, the researchers report that the probiotics reduced liver tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis, the process by which the body generates new blood vessels from existing ones, which is essential for tumor growth. They found significantly raised levels of hypoxic GLUT-1+, indicating that tumor reductions were due to hypoxia caused by reduced blood flow. Further, the tumors in the treated mice had 52 percent lower blood vessel area and 54 percent fewer vessel sprouts than the untreated mice.

They also determined that Prohep treatment down-regulated IL-17, a pro-inflammatory angiogenic factor. Because HCC is a highly vascularized tumor, the cancer is generally associated with high levels of IL-17 and an immune T-cell called T helper 17 (Th17), which is transported from the gut to HCC tumors via circulation. The researchers believe that reduced Th17 in tumor cells impedes the inflammation and angiogenesis and limits tumor growth. It's not surprising that they also found that probiotics increased the anti-inflammatory bacteria and metabolites present in the guts of treated mice. They conclude that Prohep intake has the capability of inhibiting tumor progression by modulating the gut microbiota.

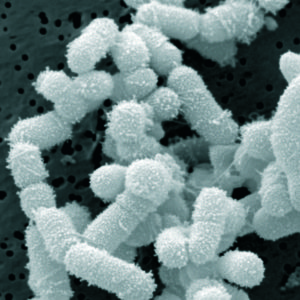

Another microbe that causes Lyme disease! Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in the northern hemisphere, and it is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Recently Mayo Clinic researchers found a new bacteria, which they named Borrelia mayonii, in the fluids and tissues of some people diagnosed with Lyme disease in the upper midwestern USA. The symptoms are different from typical Lyme disease: with nausea and vomiting, diffuse rashes (rather than a single bull's-eye rash), and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood. Same treatment as with the original bacteria , but it may not show up in tests for Lyme disease.

Another microbe that causes Lyme disease! Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in the northern hemisphere, and it is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Recently Mayo Clinic researchers found a new bacteria, which they named Borrelia mayonii, in the fluids and tissues of some people diagnosed with Lyme disease in the upper midwestern USA. The symptoms are different from typical Lyme disease: with nausea and vomiting, diffuse rashes (rather than a single bull's-eye rash), and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood. Same treatment as with the original bacteria , but it may not show up in tests for Lyme disease. The finding that the oral bacteria Streptococcus mutans, which is found in 10% of the population, is linked with hemorrhagic strokes is big. S. mutans is found in tooth decay or cavities (dental caries). The researchers found a link with cnm-positive S. mutans with both intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and also with cerebral microbleeds.

The finding that the oral bacteria Streptococcus mutans, which is found in 10% of the population, is linked with hemorrhagic strokes is big. S. mutans is found in tooth decay or cavities (dental caries). The researchers found a link with cnm-positive S. mutans with both intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and also with cerebral microbleeds. A recent study has examined the issue of whether the 10 to 1 ratio of bacteria to human cells, which is widely quoted, is actually correct. Weizmann Institute of Science researchers currently feel that based on scientific evidence (which of course will change over time) and making "educated estimates", the actual ratio is closer to 1:1 (but overall there still are more bacterial than human cells). They point out that the 10:1 ratio was originally a "back of the envelope" estimate dating back to 1972.

A recent study has examined the issue of whether the 10 to 1 ratio of bacteria to human cells, which is widely quoted, is actually correct. Weizmann Institute of Science researchers currently feel that based on scientific evidence (which of course will change over time) and making "educated estimates", the actual ratio is closer to 1:1 (but overall there still are more bacterial than human cells). They point out that the 10:1 ratio was originally a "back of the envelope" estimate dating back to 1972. I posted about this amazing research while it was still ongoing (

I posted about this amazing research while it was still ongoing ( It's now 3 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Three amazing years since I started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous.

It's now 3 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Three amazing years since I started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous.

This confirms what researchers such as

This confirms what researchers such as  Once again, two opposing views about beards have been in the news - that they harbor all sorts of nasty disease-causing bacteria vs they are hygienic. An earlier

Once again, two opposing views about beards have been in the news - that they harbor all sorts of nasty disease-causing bacteria vs they are hygienic. An earlier