This new research suggests possible future treatments in treating urinary tract infections (UTIs) by manipulating the person's diet and so influencing gut microbes and urinary pH (how acidic is the urine). These possible future treatments are different than what others are looking for, which are bacteria (probiotics) that one can take to prevent or treat UTIs. (Earlier posts on treating UTIs are here and here,)

This new research suggests possible future treatments in treating urinary tract infections (UTIs) by manipulating the person's diet and so influencing gut microbes and urinary pH (how acidic is the urine). These possible future treatments are different than what others are looking for, which are bacteria (probiotics) that one can take to prevent or treat UTIs. (Earlier posts on treating UTIs are here and here,)

The researchers found that during UTIs, humans secrete siderocalin which helps the body fight infection by depriving bacteria of iron (a mineral necessary for bacterial growth), and that samples that were less acidic, and closer to the neutral pH of pure water, showed higher activity of the protein siderocalin and were better at restricting bacterial growth than the more acidic samples.

The researchers found that the presence of small metabolites called aromatics, which vary depending on a person's diet, also contributed to variations in bacterial growth. Samples that restricted bacterial growth had more aromatic compounds, and urine that permitted bacterial growth had fewer. Stay tuned for follow-up research.

One of the researchers, Dr. Jeffrey P. Henderson, pointed out that physicians already know how to raise urinary pH with things like calcium supplements, and alkalizing agents are already used in the U.K. as over-the-counter UTI treatments. But knowing how to encourage the metabolites is trickier, but will involve dietary changes. Some good food sources include those rich in antioxidants: coffee, tea, colorful berries, cranberries, and red wine.

From Science Daily: A person's diet, acidity of urine may affect susceptibility to UTIs

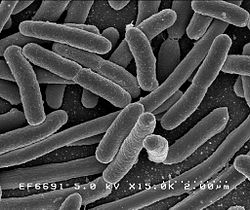

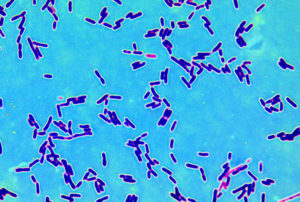

The acidity of urine -- as well as the presence of small molecules related to diet -- may influence how well bacteria can grow in the urinary tract, a new study shows. The research may have implications for treating urinary tract infections, which are among the most common bacterial infections worldwide. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) often are caused by a strain of bacteria called Escherichia coli (E. coli), and doctors long have relied on antibiotics to kill the microbes. But increasing bacterial resistance to these drugs is leading researchers to look for alternative treatment strategies.

"Many physicians can tell you that they see patients who are particularly susceptible to urinary tract infections," said senior author Jeffrey P. Henderson, MD, PhD,...With this in mind, Henderson and his team, including first author Robin R. Shields-Cutler, a graduate student in Henderson's lab, were interested in studying how the body naturally fights bacterial infections. They cultured E. coli in urine samples from healthy volunteers and noted major differences in how well individual urine samples could harness a key immune protein to limit bacterial growth. "We could divide these urine samples into two groups based on whether they permitted or restricted bacterial growth," Henderson said. "Then we asked, what is special about the urine samples that restricted growth?"

The urine samples that prevented bacterial growth supported more activity of this key protein, which the body makes naturally in response to infection, than the samples that permitted bacteria to grow easily. The protein is called siderocalin, and past research has suggested that it helps the body fight infection by depriving bacteria of iron, a mineral necessary for bacterial growth. Their data led the researchers to ask if any characteristics of their healthy volunteers were associated with the effectiveness of siderocalin.

"Age and sex did not turn out to be major players," Shields-Cutler said. "Of all the factors we measured, the only one that was really different between the two groups was pH -- how acidic or basic the urine was."Henderson said that conventional wisdom in medicine favors the idea that acidic urine is better for restricting bacterial growth. But their results were surprising because samples that were less acidic, closer to the neutral pH of pure water, showed higher activity of the protein siderocalin and were better at restricting bacterial growth than the more acidic samples.

Importantly, the researchers also showed that they could encourage or discourage bacterial growth in urine simply by adjusting the pH, a finding that could have implications for how patients with UTIs are treated.

"Physicians are very good at manipulating urinary pH," said Henderson, who treats patients with UTIs. "If you take Tums, for example, it makes the urine less acidic. But pH is not the whole story here. Urine is a destination for much of the body's waste in the form of small molecules. It's an incredibly complex medium that is changed by diet, individual genetics and many other factors."

After analyzing thousands of compounds in the samples, the researchers determined that the presence of small metabolites called aromatics, which vary depending on a person's diet, also contributed to variations in bacterial growth. Samples that restricted bacterial growth had more aromatic compounds, and urine that permitted bacterial growth had fewer.

Henderson and his colleagues suspect that at least some of these aromatics are good iron binders, helping deprive the bacteria of iron. And perhaps surprisingly, these molecules are not produced by human cells, but by a person's gut microbes as they process food in the diet."Our study suggests that the body's immune system harnesses dietary plant compounds to prevent bacterial growth," Henderson said. "We identified a list of compounds of interest, and many of these are associated with specific dietary components and with gut microbes."

Indeed, their results implicate cranberries among other possible dietary interventions. Shield-Cutler noted that many studies already have investigated extracts or juices from cranberries as UTI treatments but the results of such investigations have not been consistent.

A very important thing that we can all do to lower our exposure to toxins - heavy metals, pesticides, etc., is to take off our shoes at the door. A

A very important thing that we can all do to lower our exposure to toxins - heavy metals, pesticides, etc., is to take off our shoes at the door. A  Hah! A study that builds on what is already known by many women - that the non-prescription product D-mannose works for urinary tract infections (UTIs). D-mannose is amazingly effective for urinary tract infections caused by E. coli bacteria (up to 90% of UTIs), even infections that keep recurring (30 to 50% of infections), and which don't respond to numerous antibiotics.

Hah! A study that builds on what is already known by many women - that the non-prescription product D-mannose works for urinary tract infections (UTIs). D-mannose is amazingly effective for urinary tract infections caused by E. coli bacteria (up to 90% of UTIs), even infections that keep recurring (30 to 50% of infections), and which don't respond to numerous antibiotics. OK, the study results sound promising: that washing with cold water is as good as washing with warm or hot water for removing bacteria from the hands. And that type of soap didn't matter - both the anti-microbial soap and ordinary soap were equally effective. But...the researchers only looked at one strain of bacteria - E. coli (full name Escherichia coli (ATCC 11229)), and there are MANY microbes and viruses out there that cause problems. So I would view it as a nice start ( a preliminary study), but not the final word. From Science Daily:

OK, the study results sound promising: that washing with cold water is as good as washing with warm or hot water for removing bacteria from the hands. And that type of soap didn't matter - both the anti-microbial soap and ordinary soap were equally effective. But...the researchers only looked at one strain of bacteria - E. coli (full name Escherichia coli (ATCC 11229)), and there are MANY microbes and viruses out there that cause problems. So I would view it as a nice start ( a preliminary study), but not the final word. From Science Daily: Here is an amazing short video for those interested in seeing how bacteria mutate and grow when exposed to antibiotics - and evolving to become superbugs. Researchers filmed an experiment that created bacteria a thousand times more drug-resistant than their ancestors. In the time-lapse video, a white bacterial colony (E.coli bacteria) creeps across an enormous black petri dish plated with vertical bands of successively higher doses of antibacterial drugs (antibiotics).

Here is an amazing short video for those interested in seeing how bacteria mutate and grow when exposed to antibiotics - and evolving to become superbugs. Researchers filmed an experiment that created bacteria a thousand times more drug-resistant than their ancestors. In the time-lapse video, a white bacterial colony (E.coli bacteria) creeps across an enormous black petri dish plated with vertical bands of successively higher doses of antibacterial drugs (antibiotics). Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. (

Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. ( This new research suggests possible future treatments in treating urinary tract infections (UTIs) by manipulating the person's diet and so influencing gut microbes and urinary pH (how acidic is the urine). These possible future treatments are different than what others are looking for, which are bacteria (probiotics) that one can take to prevent or treat UTIs. (Earlier posts on treating UTIs are

This new research suggests possible future treatments in treating urinary tract infections (UTIs) by manipulating the person's diet and so influencing gut microbes and urinary pH (how acidic is the urine). These possible future treatments are different than what others are looking for, which are bacteria (probiotics) that one can take to prevent or treat UTIs. (Earlier posts on treating UTIs are