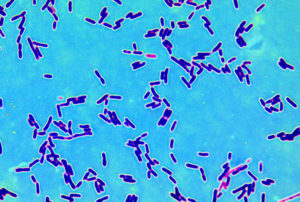

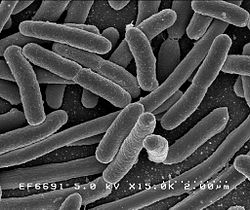

Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. (See post on their earlier work on breast microbiome.) And not only that, but the types of bacteria (Lactobacillus and Streptococcus) that are more prevalent in the breasts of healthy women are considered "beneficial" and may actually protect them from breast cancer. Meanwhile, elevated levels of the bacteria Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis found in the breast tissue adjacent to tumors are the kind that do harm (e.g., known to induce double-stranded breaks in DNA) . This research raises the question: could probiotics (beneficial bacteria) protect breasts from cancer? From Science Daily:

Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. (See post on their earlier work on breast microbiome.) And not only that, but the types of bacteria (Lactobacillus and Streptococcus) that are more prevalent in the breasts of healthy women are considered "beneficial" and may actually protect them from breast cancer. Meanwhile, elevated levels of the bacteria Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis found in the breast tissue adjacent to tumors are the kind that do harm (e.g., known to induce double-stranded breaks in DNA) . This research raises the question: could probiotics (beneficial bacteria) protect breasts from cancer? From Science Daily:

Beneficial bacteria may protect breasts from cancer

Bacteria that have the potential to abet breast cancer are present in the breasts of cancer patients, while beneficial bacteria are more abundant in healthy breasts, where they may actually be protecting women from cancer, according to Gregor Reid, PhD, and his collaborators. These findings may lead ultimately to the use of probiotics to protect women against breast cancer. The research is published in the ahead of print June 24 in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

In the study, Reid's PhD student Camilla Urbaniak obtained breast tissues from 58 women who were undergoing lumpectomies or mastectomies for either benign (13 women) or cancerous (45 women) tumors, as well as from 23 healthy women who had undergone breast reductions or enhancements. They used DNA sequencing to identify bacteria from the tissues, and culturing to confirm that the organisms were alive.

Women with breast cancer had elevated levels of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis, are known to induce double-stranded breaks in DNA in HeLa cells, which are cultured human cells. "Double-strand breaks are the most detrimental type of DNA damage and are caused by genotoxins, reactive oxygen species, and ionizing radiation," the investigators write. The repair mechanism for double-stranded breaks is highly error prone, and such errors can lead to cancer's development.

Conversely, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus, considered to be health-promoting bacteria, were more prevalent in healthy breasts than in cancerous ones. Both groups have anticarcinogenic properties. For example, natural killer cells are critical to controlling growth of tumors, and a low level of these immune cells is associated with increased incidence of breast cancer. Streptococcus thermophilus produces anti-oxidants that neutralize reactive oxygen species, which can cause DNA damage, and thus, cancer.

The motivation for the research was the knowledge that breast cancer decreases with breast feeding, said Reid. "Since human milk contains beneficial bacteria, we wondered if they might be playing a role in lowering the risk of cancer. Or, could other bacterial types influence cancer formation in the mammary gland in women who had never lactated? To even explore the question, we needed first to show that bacteria are indeed present in breast tissue." (They had showed that in earlier research.)

But lactation might not even be necessary to improve the bacterial flora of breasts. "Colleagues in Spain have shown that probiotic lactobacilli ingested by women can reach the mammary gland," said Reid. "Combined with our work, this raises the question, should women, especially those at risk for breast cancer, take probiotic lactobacilli to increase the proportion of beneficial bacteria in the breast? To date, researchers have not even considered such questions, and indeed some have balked at there being any link between bacteria and breast cancer or health."

Besides fighting cancer directly, it might be possible to increase the abundance of beneficial bacteria at the expense of harmful ones, through probiotics, said Reid. Antibiotics targeting bacteria that abet cancer might be another option for improving breast cancer management, said Reid. In any case, something keeps bacteria in check on and in the breasts, as it does throughout the rest of the body, said Reid. "What if that something was other bacteria--in conjunction with the host immune system?

Amazing! We each release a "personal microbial cloud" with its own "microbial cloud signature" every day. The unique combination of millions of bacteria (from our microbiome or community of microbes - including bacteria, viruses, fungi - that live within and on us) can identify us. Not only do we each give off a unique combination, but we each give off different amounts of microbes - some more, some less. Some very common bacteria: Streptococcus, Propionobacterium, Corynebacterium, and Lactobacillus (among women).The microbes are given off with every movement, every exhalation, every scratching of the head, every burp and fart, etc. - and they go in the air around the person and settle around the person (they researchers even collected bacteria from dishes set on the ground around the person). From Science Daily:

Amazing! We each release a "personal microbial cloud" with its own "microbial cloud signature" every day. The unique combination of millions of bacteria (from our microbiome or community of microbes - including bacteria, viruses, fungi - that live within and on us) can identify us. Not only do we each give off a unique combination, but we each give off different amounts of microbes - some more, some less. Some very common bacteria: Streptococcus, Propionobacterium, Corynebacterium, and Lactobacillus (among women).The microbes are given off with every movement, every exhalation, every scratching of the head, every burp and fart, etc. - and they go in the air around the person and settle around the person (they researchers even collected bacteria from dishes set on the ground around the person). From Science Daily: Another article from results of the crowdsourced study in which household dust samples were sent to researchers at the University of Colorado from approximately 1200 homes across the United States. Some findings after the dust was analyzed: differences were found in the dust of households that were occupied by more males than females and vice versa, indoor fungi mainly comes from the outside and varies with the geographical location of the house, bacteria is determined by the

Another article from results of the crowdsourced study in which household dust samples were sent to researchers at the University of Colorado from approximately 1200 homes across the United States. Some findings after the dust was analyzed: differences were found in the dust of households that were occupied by more males than females and vice versa, indoor fungi mainly comes from the outside and varies with the geographical location of the house, bacteria is determined by the  How does the medical profession currently view probiotics in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially recurrent infections? Answer: Only a few studies have been done, but what little is known is promising, which is good because traditional antibiotic treatment has problems (especially antibiotic resistance).

How does the medical profession currently view probiotics in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially recurrent infections? Answer: Only a few studies have been done, but what little is known is promising, which is good because traditional antibiotic treatment has problems (especially antibiotic resistance). Healthy women were followed during their pregnancies and postpartum, and it was found that vaginal microbial communities change over the course of pregnancy, and then really change postpartum. They also found differences in the predominant Lactobacillus bacteria species between the women. In this study it was found that Lactobacillus bacteria were most dominant during pregnancy, especially L. gaserii, L. crispatus, L. iners, and L. jensenii, and there were ethnic differences in the species. And they found that the vaginal microbiome changes postpartum, with bacteria becoming more diverse and the numbers of Lactobacillus dropping. The message here is that what are "normal and healthy" microbial communities can vary between women (in this study

Healthy women were followed during their pregnancies and postpartum, and it was found that vaginal microbial communities change over the course of pregnancy, and then really change postpartum. They also found differences in the predominant Lactobacillus bacteria species between the women. In this study it was found that Lactobacillus bacteria were most dominant during pregnancy, especially L. gaserii, L. crispatus, L. iners, and L. jensenii, and there were ethnic differences in the species. And they found that the vaginal microbiome changes postpartum, with bacteria becoming more diverse and the numbers of Lactobacillus dropping. The message here is that what are "normal and healthy" microbial communities can vary between women (in this study

Excerpts from a very interesting NPR interview with Dr. Martin Blaser and his views on the human microbiome. The big take-away: our modern life-style is not good for the gut microbiome. His recently published book is Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics is Fueling Our Modern Plagues.

Excerpts from a very interesting NPR interview with Dr. Martin Blaser and his views on the human microbiome. The big take-away: our modern life-style is not good for the gut microbiome. His recently published book is Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics is Fueling Our Modern Plagues.