Another study reporting health benefits of drinking tart cherry juice, specifically in speeding recovery following prolonged, repeat sprint activity (think soccer and rugby). The researchers found that after a prolonged, intermittent sprint activity, the cherry juice significantly lowered levels of Interleukin-6, a marker for inflammation and that there was a decrease in muscle soreness. The study participants drank the cherry juice (1 oz cherry juice concentrate mixed with 100 ml water) for several days before and several days after the sprint activity. Montmorency tart cherry juice is a polyphenol rich food that is already used by many professional sports teams to aid recovery. From Medical Xpress:

Another study reporting health benefits of drinking tart cherry juice, specifically in speeding recovery following prolonged, repeat sprint activity (think soccer and rugby). The researchers found that after a prolonged, intermittent sprint activity, the cherry juice significantly lowered levels of Interleukin-6, a marker for inflammation and that there was a decrease in muscle soreness. The study participants drank the cherry juice (1 oz cherry juice concentrate mixed with 100 ml water) for several days before and several days after the sprint activity. Montmorency tart cherry juice is a polyphenol rich food that is already used by many professional sports teams to aid recovery. From Medical Xpress:

New study: Montmorency tart cherry juice found to aid recovery of soccer players

Montmorency tart cherry juice may be a promising new recovery aid for soccer players following a game or intense practice. A new study published in Nutrients found Montmorency tart cherry juice concentrate aided recovery among eight semi-professional male soccer players following a test that simulated the physical and metabolic demands of a soccer game .The U.K. research team, led by Glyn Howatson at Northumbria University, conducted this double-blind, placebo-controlled study to identify the effects of Montmorency tart cherry juice on recovery among a new population of athletes following prolonged, intermittent exercise..... many teams in professional and international soccer and rugby already use Montmorency tart cherry juice to aid recovery."

The study involved 16 semi-professional male soccer players aged 21 to 29 who were randomly assigned to either a Montmorency tart cherry concentrate group or a placebo control group. Montmorency group participants consumed about 1 ounce (30 ml) of a commercially available Montmorency tart cherry juice concentrate mixed with 100 ml of water twice per day (8 a.m. and 6 p.m.) for seven consecutive days—for four days prior to the simulated trial and for three days after the trial. Following the same schedule, placebo group participants consumed a calorie-matched fruit cordial with less than 5 percent fruit mixed with water and maltodextrin. The 30 ml dosage of Montmorency tart cherry juice concentrate contained a total anthocyanin content of 73.5 mg, or the equivalent of about 90 whole Montmorency tart cherries.

Montmorency tart cherry juice, compared to a placebo, was found to maintain greater functional performance, impact a key marker of inflammation and decrease self-reported muscle soreness among study participants following prolonged activity that mirrors the demands of field-based sports. While additional research is needed, the authors suggest the dampening of the post-exercise inflammatory processes may be responsible.

Across every performance measure, including maximal voluntary isometric contraction, countermovement jump height, 20 m sprint time, knee extensors, 5-0-5 agility, the Montmorency group showed better performance than the placebo group. Additionally, the Montmorency group showed significantly lower levels of Interleukin-6, a marker for inflammation, particularly immediately post-trial. Ratings for muscle soreness (DOMS) were significantly lower in the Montmorency group across the 72-hour post-trial period. No significant effects in muscle damage or oxidative stress were observed in either the Montmorency group or the placebo group. These data support previous research showing similar results for athletes performing marathon running, high-intensity strength training, cycling, and metabolic exercise.

A recent study compared saline nasal irrigation vs steam inhalation vs doing both saline irrigation and steam inhalation vs doing neither (the control group) for chronic or recurring sinusitis symptoms. In the study, people with a history of chronic or recurring sinusitis symptoms were randomly assigned to one of the 4 groups, and then studied 3 months and 6 months later. The results were: a modest (slight improvement) in the saline irrigation group in symptom and quality-of-life scores, but no improvement for the steam inhalation group. However, the researchers noted that the control group also had slight improvements at 3 and 6 months. Most of the improvement in the saline irrigation group was in the group that also did steam inhalation - thus perhaps some benefit to combining both.

A recent study compared saline nasal irrigation vs steam inhalation vs doing both saline irrigation and steam inhalation vs doing neither (the control group) for chronic or recurring sinusitis symptoms. In the study, people with a history of chronic or recurring sinusitis symptoms were randomly assigned to one of the 4 groups, and then studied 3 months and 6 months later. The results were: a modest (slight improvement) in the saline irrigation group in symptom and quality-of-life scores, but no improvement for the steam inhalation group. However, the researchers noted that the control group also had slight improvements at 3 and 6 months. Most of the improvement in the saline irrigation group was in the group that also did steam inhalation - thus perhaps some benefit to combining both. Another interesting study looking at whether being overweight is linked to premature death, heart attacks, and diabetes. This study looked at sets of twins, in which one is heavier than the other, and followed them long-term (average 12.4 years) and found that NO - being overweight or obese (as measured by Body Mass Index or BMI) is NOT associated with premature death or heart attack (myocardial infarction), but it is associated with higher rates of type 2 diabetes. These results are in contrast with what

Another interesting study looking at whether being overweight is linked to premature death, heart attacks, and diabetes. This study looked at sets of twins, in which one is heavier than the other, and followed them long-term (average 12.4 years) and found that NO - being overweight or obese (as measured by Body Mass Index or BMI) is NOT associated with premature death or heart attack (myocardial infarction), but it is associated with higher rates of type 2 diabetes. These results are in contrast with what  Studies have found that increased nut consumption has been associated with

Studies have found that increased nut consumption has been associated with  Yup, e-cigarettes are NOT harmless, but emit harmful compounds. Researchers detected significant levels of 31 chemical compounds, including nicotine, nicotyrine, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, glycidol, acrolein, acetol, and diacetyl. Included in the harmful emissions are carcinogens and respiratory irritants. From Science Daily:

Yup, e-cigarettes are NOT harmless, but emit harmful compounds. Researchers detected significant levels of 31 chemical compounds, including nicotine, nicotyrine, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, glycidol, acrolein, acetol, and diacetyl. Included in the harmful emissions are carcinogens and respiratory irritants. From Science Daily:

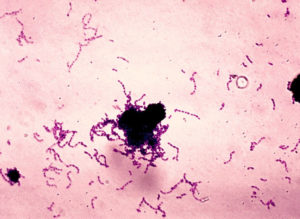

Research shows that Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria that is a main cause of tooth decay or dental caries, is passed from mother to child, and also between nonrelative children. Any interaction that involves

Research shows that Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria that is a main cause of tooth decay or dental caries, is passed from mother to child, and also between nonrelative children. Any interaction that involves  A new study followed adults with meniscus tears (in the knee), who were randomly assigned to either exercise only or meniscus repair surgery (arthroscopic partial meniscectomy) only. They found that after 2 years there was no difference between those who just received exercise therapy compared to those who just received meniscus repair surgery. About 19% of the exercise only group decided to get surgery at some point, but the rest stayed in the exercise only group.

A new study followed adults with meniscus tears (in the knee), who were randomly assigned to either exercise only or meniscus repair surgery (arthroscopic partial meniscectomy) only. They found that after 2 years there was no difference between those who just received exercise therapy compared to those who just received meniscus repair surgery. About 19% of the exercise only group decided to get surgery at some point, but the rest stayed in the exercise only group. Everyone lifting light weights during exercise workouts will be heartened by a study that found that lifting

Everyone lifting light weights during exercise workouts will be heartened by a study that found that lifting