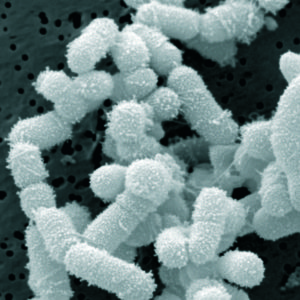

A new study has summarized what we know about fungi that live in and on babies - and yes, we all have fungi both on and within us. It's called the mycobiome. In healthy individuals all the microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc) live in balanced microbial communities, but the communities can become "out of whack" (dysbiosis) for various reasons, and microbes that formerly co-existed peacefully can multiply and become problematic. Or other pathogenic microbes can enter the community, and the person becomes ill.

A new study has summarized what we know about fungi that live in and on babies - and yes, we all have fungi both on and within us. It's called the mycobiome. In healthy individuals all the microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc) live in balanced microbial communities, but the communities can become "out of whack" (dysbiosis) for various reasons, and microbes that formerly co-existed peacefully can multiply and become problematic. Or other pathogenic microbes can enter the community, and the person becomes ill.

In healthy adults, approximately 0.1% of the microbes in the adult intestine are fungi, from approximately 60 unique species. Most species live peacefully in the body, and some fungi even have health benefits (e.g., Saccharomyces boulardii prevents gastrointestinal disease). Some fungi that many view as no good and involved with diseases (e.g., Candida and Aspergillus) are also found normally in healthy people. Studies show that normally infants also have fungi. Some fungi that live in the baby's gut (thus detected in fecal samples) are Candida (including C. albicans), Saccharomyces, and Cladosporium. The researchers (from the Univ. of Minnesota) point out that the study of fungi in babies has been neglected and much more research needs to be done.

Whether an infant is born vaginally or through cesarean delivery (C-section) affects the composition of the baby's bacterial communities over the first 6 months of life. And similarly, it looks like when the baby passes through the birth canal, the baby is exposed to the mother's mycobiota (fungi), and then these colonize in the infant's gut. Babies born by C-section have some differences in their fungi, such as being colonized by the mother's skin fungi (such as Malassezia fungi). After birth, a parent kissing and touching the baby (skin to skin contact) also transmits microbes, including fungi, to the baby.

Whether a baby drinks breast milk or formula strongly affects the infant's bacteria within the GI tract. For example, breast-fed infants have more Bifidobacteria and Labctobacilli in their gut compared to formula-fed infants. One study found about 700 species of bacteria in breast milk. Thus, scientists think that human breast milk also influences the infant gut mycobiota (fungi), although this research still needs to be done.

Whether a baby is born prematurely or at term (gestational age) is important. For infants born prematurely, intestinal fungi can cause big problems, such as an overgrowth in the gut. For example, 10% of premature babies get invasive, systemic Candidiasis, and about 20% die. Some factors leading to this are: a naïve immune system, bacterial communities out of whack (dysbiosis) due to antibiotic exposure, and use of parenteral nutrition (because this doesn't contain all the microbes from the mother that are in breast milk). In premature infants, beneficial fungi such as S. boulardii, may help to regulate the growth of opportunistic fungal colonizers such as Candida.

it is clear that whether the baby received antibiotics is important. The bacterial community of infants is altered by exposure to antibiotics in both term and preterm infants. For example, in a lengthy study over the first 3 years of life, infants receiving multiple courses of antibiotics had bacterial community changes following antibiotics and their gut bacterial microbiome became less diverse (fewer species). Although most commonly used antibiotics do not directly act on fungi, anti-bacterial antibiotic exposure is associated with alterations to the mycobiota (fungi) - such as increased rates of fungal colonization, fungal overgrowth, and changes in the fungal community. For ex., premature infants exposed to cephalosporin antibiotics have an increased risk for invasive Candidiasis (a fungal overgrowth).

Out of whack (dysbiotic) microbial communities, incuding fungi, are found in IBD (intestinal bowel diseases) in children. They have more of some fungi (e.g. Pichia jadinii and Candida parapsilosis) and less of Cladosporium cladosporiodes, and an overall decrease in fungal diversity in the gut, as compared to healthy children.

From BMC Medicine: Infant fungal communities: current knowledge and research opportunities

The microbes colonizing the infant gastrointestinal tract have been implicated in later-life disease states such as allergies and obesity. Recently, the medical research community has begun to realize that very early colonization events may be most impactful on future health, with the presence of key taxa required for proper immune and metabolic development. However, most studies to date have focused on bacterial colonization events and have left out fungi, a clinically important sub-population of the microbiota. A number of recent findings indicate the importance of host-associated fungi (the mycobiota) in adult and infant disease states, including acute infections, allergies, and metabolism, making characterization of early human mycobiota an important frontier of medical research. This review summarizes the current state of knowledge with a focus on factors influencing infant mycobiota development and associations between early fungal exposures and health outcomes. We also propose next steps for infant fungal mycobiome research....

A new study found differences in gut microbes between active women (they exercised at least the recommended amount) and those that are sedentary. When the gut bacteria were analyzed with modern tests (genetic sequencing) the active women had more of the health promoting beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila than the sedentary women. The

A new study found differences in gut microbes between active women (they exercised at least the recommended amount) and those that are sedentary. When the gut bacteria were analyzed with modern tests (genetic sequencing) the active women had more of the health promoting beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila than the sedentary women. The  After writing about Lactobacillus sakei in the sinuses for several years (present in healthy sinuses, absent or less in those with chronic sinusitis, and also a treatment for chronic sinusitis), I wondered whether L. sakei is found anywhere else in the body. Today I read a study (conducted in Japan) about gut microbes and strokes and there it was - the presence of L. sakei in the gut.

After writing about Lactobacillus sakei in the sinuses for several years (present in healthy sinuses, absent or less in those with chronic sinusitis, and also a treatment for chronic sinusitis), I wondered whether L. sakei is found anywhere else in the body. Today I read a study (conducted in Japan) about gut microbes and strokes and there it was - the presence of L. sakei in the gut. Interesting idea - that perhaps our community of gut microbes being out of whack (dysbiosis) leads to hypertension. This study was done in both humans and mice - with an analysis of bacteria in both

Interesting idea - that perhaps our community of gut microbes being out of whack (dysbiosis) leads to hypertension. This study was done in both humans and mice - with an analysis of bacteria in both  For years it has been known that most children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have all sorts of gastrointestinal (GI) problems (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, stomach pain, food intolerance), and the more severe the autism, the more severe the GI problems. Recent studies suggested that a major factor in this are abnormal gut bacteria, with the gut microbial community out of whack (dysbiosis). Previous studies looking at the

For years it has been known that most children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have all sorts of gastrointestinal (GI) problems (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, stomach pain, food intolerance), and the more severe the autism, the more severe the GI problems. Recent studies suggested that a major factor in this are abnormal gut bacteria, with the gut microbial community out of whack (dysbiosis). Previous studies looking at the  The research finding of

The research finding of  An interesting study that showed that when gut microbes are deprived of dietary fiber (their food) they start to eat the natural layer of mucus that lines the colon. (The

An interesting study that showed that when gut microbes are deprived of dietary fiber (their food) they start to eat the natural layer of mucus that lines the colon. (The  A thick mucus layer (green), generated by the cells of the colon's wall, provides protection against invading bacteria and other pathogens. This image of a mouse's colon shows the mucus (green) acting as a barrier for the "goblet" cells (blue) that produce it. Credit: University of Michigan

A thick mucus layer (green), generated by the cells of the colon's wall, provides protection against invading bacteria and other pathogens. This image of a mouse's colon shows the mucus (green) acting as a barrier for the "goblet" cells (blue) that produce it. Credit: University of Michigan Guidelines for how to prevent food allergies in children are changing. Until very recently, it was avoid, avoid, avoid exposing babies or young children to any potential allergens. Remember parents being advised that if an allergy to X (whether pets or food) runs in the family, then absolutely avoid exposing the child to the potential allergen? Well, recent research (

Guidelines for how to prevent food allergies in children are changing. Until very recently, it was avoid, avoid, avoid exposing babies or young children to any potential allergens. Remember parents being advised that if an allergy to X (whether pets or food) runs in the family, then absolutely avoid exposing the child to the potential allergen? Well, recent research (