A wonderful journal article from March 17, 2015 by E.K. Cope and S.V. Lynch (one of the original L. sakei - sinusitis researchers) in which they discuss various probiotic (beneficial bacteria) species that might have some benefit in treating chronic sinusitis, which they refer to as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). They discuss bacteria that have have been (somewhat) studied in humans or mice and could have potential in sinusitis treatment: Lactobacillus sakei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus johnsonii, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. [NOTE: So few studies (almost none) have been done with probiotics in CRS that the odds are really good that other species of bacteria, or combinations of bacteria, will also prove to be beneficial.]

A wonderful journal article from March 17, 2015 by E.K. Cope and S.V. Lynch (one of the original L. sakei - sinusitis researchers) in which they discuss various probiotic (beneficial bacteria) species that might have some benefit in treating chronic sinusitis, which they refer to as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). They discuss bacteria that have have been (somewhat) studied in humans or mice and could have potential in sinusitis treatment: Lactobacillus sakei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus johnsonii, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. [NOTE: So few studies (almost none) have been done with probiotics in CRS that the odds are really good that other species of bacteria, or combinations of bacteria, will also prove to be beneficial.]

It seems that a nasal spray with a mixture of beneficial bacteria may ultimately work the best because the bacterial diversity of the sinus microbiome is depleted in persons with chronic sinusitis, and there is "enrichment of sinus pathogens" (bacteria that can cause disease). As I've mentioned in other posts, S.V. Lynch is involved in developing a nasal probiotic spray containing L. sakei and other Lactobacillus species to treat sinusitis, but it is unknown when that will be available.

The authors also made the point that probiotics (beneficial bacteria) may work several ways in the sinus microbiome (a community of microbes living in the sinuses). This "niche" with its own ecosystem or community of species can be altered, with some bacteria species wiped out, perhaps by illness and/or repeated courses of antibiotics. Therefore, think of the different microbial species in the sinus microbiome as having different functions: as a keystone (a species that has a very large effect on the community), pioneer (species that are the first to colonize the niche after a disruption), or dominant species found in a healthy state (species with a relatively high abundance in a niche).

They also discuss what are the main pathogens found in chronic sinusitis, but they also mention that bacteria that we think of as pathogenic (the bad bacteria) are also present in healthy persons - just at a lower level than in chronic sinusitis sufferers. Also, these diverse microbial communities can vary between healthy individuals - that is, the healthy microbial communities are a little different among people. Common pathogenic bacteria found in CRS are: Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum (normally a harmless skin bacteria), and Streptococcus species. Remember, healthy sinuses have greater bacterial diversity than sinusitis sufferers, and CRS patients have "substantial microbiome dysbiosis" (microbial communities out-of-whack), with "microbiome community collapse" and "enrichment of specific sinus pathogens". In other words, the microbial sinus communities in CRS are in bad shape and need to get good bacteria in there.

For information on how some people are already successfully using probiotics such as L. sakei for sinusitis treatment, read The One Probiotic That Treats Sinusitis (products, brands, and methods).

When reading the following, remember that dysbiosis means "the microbial community is out of whack". Some excerpts from the Cope and Lynch article from Current Allergy and Asthma Reports:

Novel Microbiome-Based Therapeutics for Chronic Rhinosinusitis

The human microbiome, i.e. the collection of microbes that live on, in and interact with the human body, is extraordinarily diverse; microbiota have been detected in every tissue of the human body interrogated to date. Resident microbiota interact extensively with immune cells and epithelia at mucosal surfaces including the airways, and chronic inflammatory and allergic respiratory disorders are associated with dysbiosis of the airway microbiome. Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a heterogeneous disease with a large socioeconomic impact, and recent studies have shown that sinus inflammation is associated with decreased sinus bacterial diversity and the concomitant enrichment of specific sinus pathogens.

Similar to other chronic inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and asthma, evidence is emerging for the role of the sinus microbiome in defining upper airway health.....two trends in the literature are evident. First, all three studies that have examined the microbiota of healthy subjects demonstrate the presence of a diverse microbiome that includes bacterial groups classically considered as causative agents of respiratory disease, including Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus. Second, substantial sinonasal microbiome dysbiosis is associated with CRS. In one example, Abreu and colleagues demonstrated microbiome community collapse in the maxillary sinuses of CRS patients compared to healthy controls characterized by the outgrowth of Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. In another study, nasal lavage specimens from CRS patients revealed microbiome collapse coincident with Staphylococcus enrichment.

Immune responses in individuals with CRS vary considerably across patients.... While the underlying processes contributing to a patient’s immune response are not well understood, there is evidence for microbial stimulation. Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins are associated with a Th2 inflammatory response characterized by eosinophilia and enterotoxin-specific IgE , and the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 have been associated with S. aureus outgrowth in other inflammatory diseases. Another common sinus pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can induce antimicrobial nitric oxide production by host recognition of bacterial quorum sensing molecules through stimulation of the bitter taste receptor T2R38. There is clearly heterogeneity across patients with CRS; thus, future therapeutic microbiome manipulation strategies must be targeted to the specific microbiome perturbation and immune dysfunction of the patient.

Since CRS is immunologically and microbiologically diverse, it is not surprising that current treatment strategies using corticosteroids alone or in combination with antibiotics are variably successful. Some patients recover completely without recurrence, although 10–25 % of patients require repeated treatment....Patients who do not respond to medical management are candidates for functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS). The goal of FESS is to remove polypoid tissue and open ostia to facilitate sinus drainage. While some patients rebuild their native, healthy microbial communities and epithelium following FESS, many patients require revision sinus surgeries. Importantly, these therapies only manage chronic airway diseases and, in many cases, do not address the underlying source of disease, e.g., dysregulated microbiota. Since it is clear that the microbiome plays a fundamental role in respiratory health, it is essential to begin to define the interaction between pathogens or pathobionts in the context of the healthy host microbiota.

As discussed above, the most common route of probiotic delivery (oral) takes advantage of the GI-respiratory axis. In the only clinical trial of probiotic use in chronic rhinosinusitis, Mukerji and colleagues reported that oral administration of L. rhamnosus R0011 improved patient-reported symptoms of rhinosinusitis in the short term (<4 weeks), but not the long term (8 weeks). These results suggest a potential role for GI microbiome manipulation to affect the sinus immune response; however, there has not been a follow-up study to further elucidate this role. Repeated dosing or inoculation with mixed species could improve these results.

Several variables should be considered when designing probiotics for potential treatment of sinus disease. The first consideration, the route of administration, will determine the mechanism of action of the probiotic. Oral probiotic supplements primarily affect the respiratory tract through translocation of microbial metabolites, cytokines, or immune cells to the airways via systemic circulation, while local delivery via sprays or nasal lavage will affect the sinonasal microbiota and local immune responses...This first variable, route of administration, will determine which probiotic species are used. A second consideration for probiotic development is whether to supplement with a single species or a mixed-species consortium. Single species or species mixtures can be selected based on how best to leverage the healthy microbiome. From an ecological perspective, the potential role of the probiotic(s) should be considered. For example, the specie(s) may function as keystone (a species that has a disproportionately large effect on the community), pioneer (species that are the first to colonize the niche after a disruption), or dominant species found in a healthy state (species with a relatively high abundance in a niche).

Animal models are powerful tools for exploring the relationship of the host-microbiome to health and disease.... In malnourished mice, nasal instillation of Lactobacillus casei can confer protection against pathogens by enhancing host innate immune response....Live L. casei had additional benefits of temporarily colonizing the respiratory mucosa to competitively exclude S. pneumonia. Intranasal administration of Lactobacillus plantarum DK119 protected mice from lethal loads of influenza A virus through modulating host immunity of alveolar dendritic cells and macrophages. Similarly, intranasal administration of L. rhamnosus GG protected mice from H1N1 influenza infection by activating lung natural killer cells..... They also show that this protection can be achieved through feeding a single species L. johnsonii, which was enriched in the cecum of mice fed house dust.... In a sinusitis model, Abreu and colleagues demonstrated that intranasal administration of Lactobacillus sakei, identified using 16S rRNA phylogenetic microarray analysis of healthy human sinuses, protects against C. tuberculostearicum-induced sinusitis. A similar murine study showed that Staphylococcus epidermidis can protect against S. aureus-induced sinusitis. Together, these studies show promise for microbiome based therapeutics in sinusitis. However, we must think critically about the species or community used for sinus protection, administration methods, as well as the timing for microbial intervention

Probiotic administration can influence the host-microbiome composition and function directly through production of antimicrobials, changing the pH, or through competitive colonization within a niche. Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides produced by bacteria with a wide range of activity, either narrow spectrum (active against similar species) or broad spectrum (active across genera). Lactic acid bacteria are well-established producers of bacteriocins. The protective species identified by Abreu and colleagues, L. sakei, is known to produce several bacteriocins with a wide range of characteristics and putative modes of action, although the best characterized bacteriocin from this species is sakacin. Sakacin has antimicrobial activity against Gram positive taxa, including Listeria spp. and Enterococcus spp., but not Gram-negative bacteria.

Other Lactobacillus species that are potential probiotics for the airways act through the production of alternative antimicrobial compounds. Lactobacillus reuteri produces the protein reuterin, which acts as an antimicrobial compound by inducing oxidative stress in competing bacteria. Reuterin production is increased in the presence of E. coli, suggesting that the effects of this protein are aimed at eliminating competing microbes, giving L. reuteri an advantage in adherence and colonization of host mucosa. Lactobacillus spp. also commonly produce acetic acid and lactic acid, thereby lowering the pH of their niche and inhibiting the growth of acid-intolerant taxa. Finally, probiotic species can compete for growth substrates or receptor binding sites. L. johnsonii competes with several known pathogens for adhesion receptors, which are either glycoproteins or glycolipids. One such receptor is gangliotetraosylceramide (asialo-GM1), a glycolipid that is abundant in pulmonary tissue.

Probiotic intervention for respiratory diseases is an area of active investigation, particularly in light of recent microbiome findings. While the field is still relatively nascent, the potential for probiotic manipulation of the sinus microbiome to treat or prevent CRS is great. However, our current understanding of the healthy sinus microbiome and, thus, how best to manipulate it in a disease state are not well defined. Whether to use mixed versus single species and strain inocula, specific species used, mode of delivery, inoculum concentration, and determining the frequency of supplementation are some of the factors that need to be addressed in optimizing probiotic effects. Most of the studies discussed in this article have focused on the gut microbiome and effects at distal sites because these interactions have formed the focus of the majority of stduies to date. However, the murine [mouse] studies discussed here suggest that local administration of probiotics to the sinuses can affect the dynamics of the sinus microbiome.

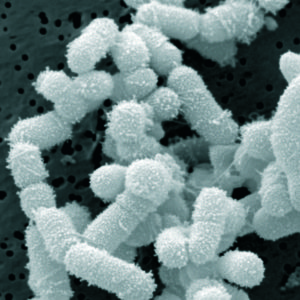

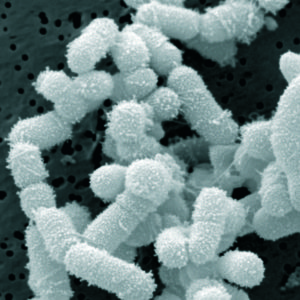

Lactobacillus sakei Credit: BacMap Genome Atlas

Lactobacillus sakei Credit: BacMap Genome Atlas

Another view of type 2 diabetes - that the gut microbiome is involved, specifically two gut bacteria: Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus. View them as the bad guys. The researchers point out "... the majority of overweight and obese individuals are insulin resistant and it is well known that dietary shifts to less calorie-dense eating and increased daily intake of any kind of vegetables and less intake of food rich in animal fat tend to normalize imbalances of gut microbiota and simultaneously improve insulin sensitivity of the host." In other words, eat more vegetables and fewer calories (if you're overweight or obese) to improve the gut microbes. This is similar to yesterday's post of research that viewed type 2 diabetes as "a response to overnutrition" and potentially reversible. From Medical Express:

Another view of type 2 diabetes - that the gut microbiome is involved, specifically two gut bacteria: Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus. View them as the bad guys. The researchers point out "... the majority of overweight and obese individuals are insulin resistant and it is well known that dietary shifts to less calorie-dense eating and increased daily intake of any kind of vegetables and less intake of food rich in animal fat tend to normalize imbalances of gut microbiota and simultaneously improve insulin sensitivity of the host." In other words, eat more vegetables and fewer calories (if you're overweight or obese) to improve the gut microbes. This is similar to yesterday's post of research that viewed type 2 diabetes as "a response to overnutrition" and potentially reversible. From Medical Express:

Newly published research found that children who are thumb-suckers or nail-biters are

Newly published research found that children who are thumb-suckers or nail-biters are  An interesting study (published in September 2015) looked at how prevalent biofilms are in the sinuses of people with chronic sinusitis (with or without nasal polyps) as compared to healthy people (without chronic sinusitis). Biofilms are communities of bacteria sticking to one another and coated with a protective slime. The researchers found that the most biofilms were found in people with chronic sinusitis who also had nasal polyps (97.1%) , followed by those with chronic sinusitis without nasal polyps (81.5%), and the least in the control group of healthy patients (56%). They felt that the biofilms contributed to or had a role in chronic sinusitis. But note that the majority of people in all groups had biofilms.

An interesting study (published in September 2015) looked at how prevalent biofilms are in the sinuses of people with chronic sinusitis (with or without nasal polyps) as compared to healthy people (without chronic sinusitis). Biofilms are communities of bacteria sticking to one another and coated with a protective slime. The researchers found that the most biofilms were found in people with chronic sinusitis who also had nasal polyps (97.1%) , followed by those with chronic sinusitis without nasal polyps (81.5%), and the least in the control group of healthy patients (56%). They felt that the biofilms contributed to or had a role in chronic sinusitis. But note that the majority of people in all groups had biofilms. sinusitis

sinusitis  Lactobacillus sakei

Lactobacillus sakei  Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. (

Amazing! Researchers found that the bacteria found in breast cancer patients and healthy patients are different. ( A study found that a combination of cranberry supplement (120 mg cranberries, with a minimum proanthocyanidin content of 32mg), the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and vitamin C (750 mg) three times a day was enough to prevent the recurrence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) for the majority of women in this small (36 patient) study. At 6 months there was a 61% success rate. No side effects were reported.

A study found that a combination of cranberry supplement (120 mg cranberries, with a minimum proanthocyanidin content of 32mg), the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and vitamin C (750 mg) three times a day was enough to prevent the recurrence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) for the majority of women in this small (36 patient) study. At 6 months there was a 61% success rate. No side effects were reported. Important new research was published in January 2016 about a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) or "poop transplant". The research compared only one patient's gut microbes (thus a case study) to her fecal transplant donor's gut microbes, but it is important for looking at how gut microbes change long-term after a fecal microbiota transplant (poop transplant) and the actual length of time that it takes for the recipient's gut microbial community to become like the donor's gut microbiome. The patient was quickly "cured" of a serious recurrent Clostridium difficile infection after one fecal micriobiota transplant (FMT) from her sister, but there were ongoing long-term changes in the patient's gut microbes for 4.5 years, at which point the microbes (bacteria and viruses) were like the donor's (at the phylum, class, and order levels), and with similar bacterial diversity. At this point the researchers said that "full engraftment" of microbes had occurred.

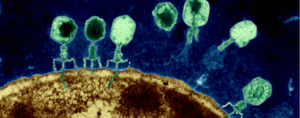

Important new research was published in January 2016 about a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) or "poop transplant". The research compared only one patient's gut microbes (thus a case study) to her fecal transplant donor's gut microbes, but it is important for looking at how gut microbes change long-term after a fecal microbiota transplant (poop transplant) and the actual length of time that it takes for the recipient's gut microbial community to become like the donor's gut microbiome. The patient was quickly "cured" of a serious recurrent Clostridium difficile infection after one fecal micriobiota transplant (FMT) from her sister, but there were ongoing long-term changes in the patient's gut microbes for 4.5 years, at which point the microbes (bacteria and viruses) were like the donor's (at the phylum, class, and order levels), and with similar bacterial diversity. At this point the researchers said that "full engraftment" of microbes had occurred. Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses

Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses  Try to avoid triclosan. Read labels (especially soaps, personal care, and household cleaning products) and avoid anything that says it contains triclosan, or is anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-microbial, or anti-odor. We easily absorb triclosan into our bodies, and it has been detected in our urine, blood, and breast milk. Among its many negative effects (e.g.,

Try to avoid triclosan. Read labels (especially soaps, personal care, and household cleaning products) and avoid anything that says it contains triclosan, or is anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-microbial, or anti-odor. We easily absorb triclosan into our bodies, and it has been detected in our urine, blood, and breast milk. Among its many negative effects (e.g.,  Dandruff is a very common scalp disorder that has occurred for centuries. A new study found that the most abundant bacteria on the scalp are Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, and that they have a reciprocal relationship with each other - when one is high, the other is low. When compared with a normal scalp, dandruff regions had decreased Propionibacterium and increased Staphylococcus. The researchers suggested that these findings suggest a new way to treat dandruff - to increase the Propionibacterium and decrease the Staphylococcus on the scalp. Stay tuned for possible future treatments using these findings. From Science Daily:

Dandruff is a very common scalp disorder that has occurred for centuries. A new study found that the most abundant bacteria on the scalp are Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, and that they have a reciprocal relationship with each other - when one is high, the other is low. When compared with a normal scalp, dandruff regions had decreased Propionibacterium and increased Staphylococcus. The researchers suggested that these findings suggest a new way to treat dandruff - to increase the Propionibacterium and decrease the Staphylococcus on the scalp. Stay tuned for possible future treatments using these findings. From Science Daily: