Uh oh - once again a drug taken for a common problem (heartburn) is linked to an unexpected negative health effect (higher risk of strokes). Millions of Americans take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to treat acid reflux and heartburn. They are among the most prescribed drugs in the United States, are frequently taken for long periods of time, and are available over the counter. But according to preliminary research presented at a 2016 American Heart Association conference, these medications may also increase the risk of ischemic stroke. Ischemic strokes, which are the most common type of stroke, occur when a blood clot cuts off blood flow to the brain.

Uh oh - once again a drug taken for a common problem (heartburn) is linked to an unexpected negative health effect (higher risk of strokes). Millions of Americans take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to treat acid reflux and heartburn. They are among the most prescribed drugs in the United States, are frequently taken for long periods of time, and are available over the counter. But according to preliminary research presented at a 2016 American Heart Association conference, these medications may also increase the risk of ischemic stroke. Ischemic strokes, which are the most common type of stroke, occur when a blood clot cuts off blood flow to the brain.

Earlier research has linked proton pump inhibitors to increased risk of dementia in older patients, disruption of gut microbes, increased risk of C. difficile infections, and kidney disease. Stomach acid seems to play a role in the normal balance of microbes in the digestive system. When someone takes PPIs it lowers their amount of stomach acid, and so disrupts the gut microbial community (and these changes last for at least a month after discontinuing the drug).

The research was conducted in Denmark among a quarter-million patients who suffered from stomach pain and indigestion, and were taking one of four PPIs: Prilosec, Protonix, Prevacid or Nexium. Overall, they found that ischemic stroke risk increased by 21% among patients who were taking a PPI. The researchers found either no increased risk or minimal increased risk of stroke when taking low doses of PPIs. But at the highest doses of PPIs, they found that stroke risk increased from 30% (Prevaacid) to a high of 94% (Protonix). Another group of medications used to treat heartburn - called H2 blockers - were not linked to increased stroke risk.

Hey, what this research suggests is that not everything should be treated with pills. Medical professionals agree: the safest and best way to reduce heartburn is by making some lifestyle changes. Eat smaller meals (and not right before bedtime), lose weight if needed, don't eat very fatty meals, drink less alcohol, and don't smoke. From EurekAlert:

Popular heartburn medication may increase ischemic stroke risk

A popular group of antacids known as proton pump inhibitors, or PPIs, used to reduce stomach acid and treat heartburn may increase the risk of ischemic stroke, according to preliminary research presented at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2016.

"PPIs have been associated with unhealthy vascular function, including heart attacks, kidney disease and dementia," said Thomas Sehested, M.D., study lead author and a researcher at the Danish Heart Foundation in Copenhagen, Denmark. "We wanted to see if PPIs also posed a risk for ischemic stroke, especially given their increasing use in the general population." Ischemic stroke, the most common type of stroke, is caused by clots blocking blood flow to or in the brain.

Researchers analyzed the records of 244,679 Danish patients, average age 57, who had an endoscopy -- a procedure used to identify the causes of stomach pain and indigestion. During nearly six years of follow up, 9,489 patients had an ischemic stroke for the first time in their lives. Researchers determined if the stroke occurred while patients were using 1 of 4 PPIs: omeprazole (Prilosec), pantoprazole (Protonix), lansoprazole (Prevacid) and esomeprazole (Nexium).

For ischemic stroke, researchers found:Overall stroke risk increased by 21 percent when patients were taking a PPI. At the lowest doses of the PPIs, there was slight or no increased stroke risk. At the highest dose for these 4 PPI's, stroke risk increased from 30 percent for lansoprazole (Prevacid) to 94 percent for pantoprazole (Protonix). There was no increased risk of stroke associated with another group of acid-reducing medications known as H2 blockers, which include famotidine (Pepcid) and ranitidine (Zantac).

Authors believe that their findings, along with previous studies, should encourage more cautious use of PPIs. Sehested noted that most PPIs in the United States are now available over the counter. Doctors prescribing PPIs, should carefully consider whether their use is warranted and for how long: "We know that from prior studies that a lot of individuals are using PPIs for a much longer time than indicated, which is especially true for elderly patients."

An

An  Could certain beneficial bacteria (probiotics) help prevent or deal with infections in burn wounds?

Could certain beneficial bacteria (probiotics) help prevent or deal with infections in burn wounds?  Lactobacillus plantarum Credit: Nature

Lactobacillus plantarum Credit: Nature My

My  We all know that exercise is beneficial for health. Research suggests that exercising out in nature is best for several varied reasons - including that it

We all know that exercise is beneficial for health. Research suggests that exercising out in nature is best for several varied reasons - including that it  The latest development in treating stubborn cases of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) are "poop pills" - pills that patients can easily swallow rather than having to go through a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). The "poop pills" are filled with blenderized fecal matter from healthy donors, are much easier for patients to swallow, and they successfully treat C. difficile at almost the same rate as fecal microbiota transplants - about 91% after 1 or 2 treatments for the pills, and 93 to 96% for FMT. This is an amazing success rate for an infection that debilitates people, is resistant to antibiotics in many cases, and even kills people.

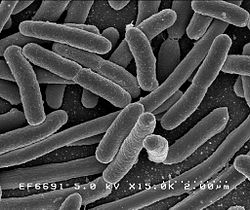

The latest development in treating stubborn cases of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) are "poop pills" - pills that patients can easily swallow rather than having to go through a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). The "poop pills" are filled with blenderized fecal matter from healthy donors, are much easier for patients to swallow, and they successfully treat C. difficile at almost the same rate as fecal microbiota transplants - about 91% after 1 or 2 treatments for the pills, and 93 to 96% for FMT. This is an amazing success rate for an infection that debilitates people, is resistant to antibiotics in many cases, and even kills people. Here is an amazing short video for those interested in seeing how bacteria mutate and grow when exposed to antibiotics - and evolving to become superbugs. Researchers filmed an experiment that created bacteria a thousand times more drug-resistant than their ancestors. In the time-lapse video, a white bacterial colony (E.coli bacteria) creeps across an enormous black petri dish plated with vertical bands of successively higher doses of antibacterial drugs (antibiotics).

Here is an amazing short video for those interested in seeing how bacteria mutate and grow when exposed to antibiotics - and evolving to become superbugs. Researchers filmed an experiment that created bacteria a thousand times more drug-resistant than their ancestors. In the time-lapse video, a white bacterial colony (E.coli bacteria) creeps across an enormous black petri dish plated with vertical bands of successively higher doses of antibacterial drugs (antibiotics). This article by Dr. Thomas E. Finucane lays out nicely a paradigm shift in how to view uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) - as a case of dysbiosis (microbial community out of whack), and that antibiotics to kill bacteria are generally not needed or helpful. (He doesn't mention it, but the next step in his argument should be that probiotic or beneficial bacteria or other microbes may improve the microbial community and symptoms.) A main point of the article is that we now know the urinary tract is not sterile - instead diverse microbiota live there (the microbial community is the

This article by Dr. Thomas E. Finucane lays out nicely a paradigm shift in how to view uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) - as a case of dysbiosis (microbial community out of whack), and that antibiotics to kill bacteria are generally not needed or helpful. (He doesn't mention it, but the next step in his argument should be that probiotic or beneficial bacteria or other microbes may improve the microbial community and symptoms.) A main point of the article is that we now know the urinary tract is not sterile - instead diverse microbiota live there (the microbial community is the