An article was just published in a research journal to discuss the fact that humans - in part due to lifestyles which include less dietary fiber (due to eating fewer varieties and amounts of plants) and due to medical practices (such as frequent use of antibiotics) has resulted in gut "bacterial extinctions". In other words, humans (especially those living an urban industrialized Western lifestyle) have fewer gut bacterial species than those living a more traditional lifestyle, and this loss of bacterial species is linked to various diseases. Humans can increase the number of certain bacterial species, but the loss of some bacterial species is forever.

An article was just published in a research journal to discuss the fact that humans - in part due to lifestyles which include less dietary fiber (due to eating fewer varieties and amounts of plants) and due to medical practices (such as frequent use of antibiotics) has resulted in gut "bacterial extinctions". In other words, humans (especially those living an urban industrialized Western lifestyle) have fewer gut bacterial species than those living a more traditional lifestyle, and this loss of bacterial species is linked to various diseases. Humans can increase the number of certain bacterial species, but the loss of some bacterial species is forever.

The researchers discuss that humans have the "lowest level of gut bacterial diversity" of any hominid and primate. They stated that the shrinking of the variety of microbial species in the human gut (the gut microbiome) began early in human evolution (as humans started eating more meat), but that it has accelerated dramatically within industrialized societies. And that evidence is accumulating that this gut bacterial "depauperation" - the loss of a variety of bacterial species - may predispose humans to a range of diseases. Some of it is due to evolution (as humans ate more meat), and some to lifestyle changes. A term is used throughout this paper: depauperate - which means lacking in numbers or variety of species in the gut microbiome (the microbial community or ecosystem).

Other research has also shown that eating a highly processed Western diet results in gut microbial changes that are linked to various diseases (here, here, here) - that is, the microbes being fed are those associated with diseases. Also, certain diets encourage certain microbial species to flourish (here, here). Bottom line: studies find health benefits from higher levels of dietary fiber - from fruits, vegetables, seeds, nuts, whole grains, and legumes (beans). From Current Opinion In Microbiology:

The shrinking human gut microbiome

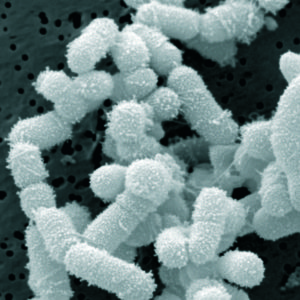

Mammals harbor complex assemblages of gut bacteria that are deeply integrated with their hosts’ digestive, immune, and neuroendocrine systems. Recent work has revealed that there has been a substantial loss of gut bacterial diversity from humans since the divergence of humans and chimpanzees. This bacterial depauperation began in humanity’s ancient evolutionary past and has accelerated in recent years with the advent of modern lifestyles. Today, humans living in industrialized societies harbor the lowest levels of gut bacterial diversity of any primate for which metagenomic data are available, a condition that may increase risk of infections, autoimmune disorders, and metabolic syndrome. Some missing gut bacteria may remain within under-sampled human populations, whereas others may be globally extinct and unrecoverable.

A typical human harbors on the order of 1013 bacterial cells in the large intestine. This gut microbiota, which can contain over a thousand species, is deeply integrated with virtually every tissue and organ system in the body. Gut bacteria process difficult to digest components of the diet, promote angiogenesis in the intestine, train the immune system, regulate metabolism, and even influence moods and behaviors.

In contrast to hunter–gatherer to agricultural transitions, adoptions of industrial and post-industrial lifestyles have led to massive reductions in bacterial richness within human gut microbiotas. Individuals living in urban centers in the United States harbor fewer gut bacterial species on average than do individuals living more traditional lifestyles in Malawi , Venezuela, Peru, and Papua New Guinea.....Industrialized and traditional lifestyles differ in many respects, confounding the identification of the specific practices that have led to decreases in gut bacterial diversity within industrialized societies. One potential cause is the rise of food processing and the corresponding reductions in the intake of dietary fiber in favor of simple sugars. Recently, studies in model systems have indicated that long-term reductions in dietary fiber can lead to the extirpation of gut bacterial taxa from host lineages.

Other potential causes of reduced gut bacterial diversity within industrialized human populations include certain modern medical practices. For example, longitudinal studies in humans have shown that levels of gut bacterial diversity decrease drastically after antibiotic use. Although bacterial richness may recover after treatment is completed, the timeline and extent of the restoration is highly subject-dependent. The consequences of antibiotic use on gut bacterial diversity may be most severe when treatment is administered during the early years of life, before the adult microbiota has fully formed .

Sooo.....what is going on here? Why are very early onset (5 years and younger) pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) in children increasing so rapidly in Canada? Inflammatory bowel diseases include

Sooo.....what is going on here? Why are very early onset (5 years and younger) pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) in children increasing so rapidly in Canada? Inflammatory bowel diseases include  More research supports that being exposed to pets during pregnancy or in the first months of life changes the gut bacteria, and in a way that is thought to be beneficial. The researchers found that infants exposed to pets prenatally or after birth (or both) had higher levels of two microbes that are associated with a lower risk of allergies and obesity. The two microbes are Ruminococcus and Oscillospira, but in case you're wondering - they are not (yet) available in probiotics

More research supports that being exposed to pets during pregnancy or in the first months of life changes the gut bacteria, and in a way that is thought to be beneficial. The researchers found that infants exposed to pets prenatally or after birth (or both) had higher levels of two microbes that are associated with a lower risk of allergies and obesity. The two microbes are Ruminococcus and Oscillospira, but in case you're wondering - they are not (yet) available in probiotics Last week a person told an

Last week a person told an  Could this be true? Probiotics for seasonal allergies? A

Could this be true? Probiotics for seasonal allergies? A  It's now 4 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Four amazing years since I (and then the rest of my family) started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous.

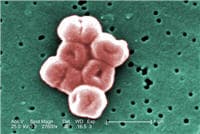

It's now 4 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Four amazing years since I (and then the rest of my family) started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous. Many posts on this blog are about beneficial microbes, and the many species of microbes (bacteria, fungi, viruses) living within and on us. But there are also bacteria in the world that pose a serious threat to human health, and the list of these are growing due to antibiotic resistance. This week the World Health Organization (WHO) officials came out with a list of a dozen antibiotic-resistant "priority pathogens" that pose the greatest threats to human health. These are bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics - thus superbugs.

Many posts on this blog are about beneficial microbes, and the many species of microbes (bacteria, fungi, viruses) living within and on us. But there are also bacteria in the world that pose a serious threat to human health, and the list of these are growing due to antibiotic resistance. This week the World Health Organization (WHO) officials came out with a list of a dozen antibiotic-resistant "priority pathogens" that pose the greatest threats to human health. These are bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics - thus superbugs. A new study has summarized what we know about fungi that live in and on babies - and yes, we all have fungi both on and within us. It's called the mycobiome. In healthy individuals all the microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc) live in balanced microbial communities, but the communities can become "out of whack" (dysbiosis) for various reasons, and microbes that formerly co-existed peacefully can multiply and become problematic. Or other pathogenic microbes can enter the community, and the person becomes ill.

A new study has summarized what we know about fungi that live in and on babies - and yes, we all have fungi both on and within us. It's called the mycobiome. In healthy individuals all the microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc) live in balanced microbial communities, but the communities can become "out of whack" (dysbiosis) for various reasons, and microbes that formerly co-existed peacefully can multiply and become problematic. Or other pathogenic microbes can enter the community, and the person becomes ill. A new study found differences in gut microbes between active women (they exercised at least the recommended amount) and those that are sedentary. When the gut bacteria were analyzed with modern tests (genetic sequencing) the active women had more of the health promoting beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila than the sedentary women. The

A new study found differences in gut microbes between active women (they exercised at least the recommended amount) and those that are sedentary. When the gut bacteria were analyzed with modern tests (genetic sequencing) the active women had more of the health promoting beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila than the sedentary women. The