Much discussion about the link between gut bacteria and liver cancer, as well as the link between inflammation and cancer. Gut microbiome imbalances can cause health harms.

Much discussion about the link between gut bacteria and liver cancer, as well as the link between inflammation and cancer. Gut microbiome imbalances can cause health harms.

Bottom line: Try to improve your gut microbiome by eating a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, seeds, nuts, legumes, and whole grains.

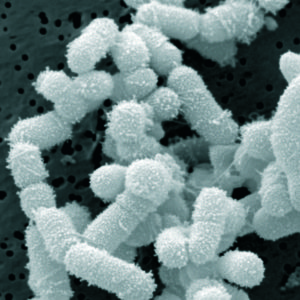

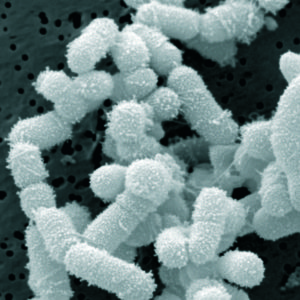

From the Dec.4, 2014 issue of Nature: Microbiome: The bacterial tightrope

Imbalances in gut bacteria have been implicated in the progression from liver disease to cancer. The team's research, published last year, suggests that gut bacteria — which are part of the microbiome of bacteria and other microorganisms that live in and on the body — can play a crucial part in liver-cancer progression.

There are trillions of microorganisms in the human microbiome — they outnumber their host's cells by around ten to one — and their exact role in health and disease is only now starting to be explored. Studies have found that people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease have a different composition of bacteria in their gut from healthy individuals2, 3

Instead, she sees an emerging picture of liver disease and cancer as a process in which various factors — including a high-fat diet, alcoholism, genetic susceptibility and the microbiome — can each contribute to the progression from minor to severe liver damage, and from severe liver damage to cancer.

Flavell's research suggests that the liver has an important role in immune surveillance and helps to maintain bacterial balance in the gut. Specialized cells in the liver and intestines monitor the microbiome by keeping tabs on bacterial by-products as they pass through. These cells can detect infections and help to fight them.

But they can also pick up on subtler changes in the bacterial populations in the gut. When certain types of bacteria become too numerous — a state called dysbiosis — the immune system becomes activated and triggers inflammation, although at a lower level than it would for an infection... Now, research is emerging that suggests that dysbiosis and the immune reaction it provokes can even contribute to cancer.

He thinks that at least part of this mechanism involves disruption in the balance of the various species of bacteria in the gut. An out-of-balance microbiome promotes a constant state of inflammation, which can contribute to cancer progression, Schwabe says. This aligns with the picture that is emerging of cancer, in general, as an inflammatory process: the same immune reactions that help the body to fight infection and disease can also promote unchecked cell growth.

Some of the earliest research on the human microbiome, published in 2006, demonstrated that the balance of gut bacteria in obese people is different from that in people of healthy weight. In particular, obese people tend to have greater numbers of the bacteria that produce DCA (deoxycholic acid) and other secondary bile acids.

This line of research points to the microbiome as one potential link between obesity and liver-cancer risk . And, much like Schwabe's work, Hara's results indicate that several factors converge to promote cancer: in this case, bacteria, diet and carcinogen exposure. Here, too, the ability to stave off the disease seems to depend on maintaining the appropriate microbial balance. Overweight mice and people have a different composition of gut microbiota from their lighter counterparts, and they have higher levels of DCA, too.

However, not everyone is convinced that individual bacterial species are to blame. Some researchers point out that dysbiosis, and therefore cancer risk, involves multiple strains of bacteria. And the bacterial mix can vary from person to person, meaning it is unlikely that scientists can pin all responsibility on a single species.

Others are looking for ways to promote the growth of healthy bacterial strains rather than target the bad ones....There is also some early clinical evidence that specially formulated probiotics — cocktails of good bacteria — can bump the microbiome back into balance. Hylemon and his colleagues gave people with cirrhosis a probiotic containing Lactobacillus bacteria and found that their blood markers of inflammation decreased along with their cognitive dysfunction (a common symptom of cirrhosis)6. Although the study was not designed to evaluate cancer risk, it does show that delivering bacteria to the gut can have positive therapeutic effects on the liver.

Much discussion about the link between gut bacteria and liver cancer, as well as the link between inflammation and cancer. Gut microbiome imbalances can cause health harms.

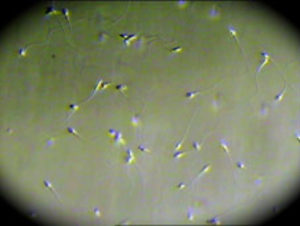

Much discussion about the link between gut bacteria and liver cancer, as well as the link between inflammation and cancer. Gut microbiome imbalances can cause health harms. Sperm under microscope. Credit: Fertility Associates Ltd. NZ

Sperm under microscope. Credit: Fertility Associates Ltd. NZ Bottom line: Try to avoid artificial sweeteners!

Bottom line: Try to avoid artificial sweeteners!