Guess what? Our microbiome (the collection of microbes living within and on us) also normally contains fungi. This is our mycobiome. Very little is known about the mycobiome. (in contrast, much, much more is known about the bacteria within us) The fungi within us may be as low as 0.1% of the total microbiota (all our microbes). But what is known is because advanced genetic analyses have been done (specifically "next-generation” sequencing") or culturing of the fungi.

Guess what? Our microbiome (the collection of microbes living within and on us) also normally contains fungi. This is our mycobiome. Very little is known about the mycobiome. (in contrast, much, much more is known about the bacteria within us) The fungi within us may be as low as 0.1% of the total microbiota (all our microbes). But what is known is because advanced genetic analyses have been done (specifically "next-generation” sequencing") or culturing of the fungi.

In some studies of fungi in healthy adults, nothing at all is known about up to 50% of the species found. And each human has a diversity or variety of fungi living within them, and these seem to vary between different parts of the body. What little is known is that fungi that we may have thought of as pathogenic (or no good) and involved in diseases (think Candida and Aspergillus) are also found normally in healthy individuals. For example, Candida were found in the mouth or oral microbiome of healthy adults as well as the gut of many healthy adults (thus part of a healthy microbial ecosystem). Some studies suggest that our diet influences which fungi species are present in the gut.

Fungi are both part of health and disease. They interact with the other microbes within us. Some fungi appear to prevent disease by competing with pathogenic organisms (bad bugs).They have functions in our body that we know very little about. We don't know much about disruptions to the fungi in our bodies or even how fungi come to live within us. The following excerpts are from a scholarly article summarizing what is known about our fungi or mycobiome. Written by Patrick C. Seed, from the Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine:

Fungi are fundamental to the human microbiome, the collection of microbes distributed across and within the body... Here, a comprehensive review of current knowledge about the mycobiome, the collective of fungi within the microbiome, highlights methods for its study, diversity between body sites, and dynamics during human development, health, and disease. Early-stage studies show interactions between the mycobiome and other microbes, with host physiology, and in pathogenic and mutualistic phenotypes. Current research portends a vital role for the mycobiome in human health and disease.

In particular, the diversity and dynamics of the so-called mycobiome, the fungi distributed on and within the body, is poorly understood, particularly in light of the considerable association of fungi with infectious diseases and allergy (Walsh and Dixon 1996). Despite being as low as ≤0.1% of the total microbiota (Qin et al. 2010), the fungal constituents of the microbiome may have key roles in maintaining microbial community structure, metabolic function, and immune-priming frontiers, which remain relatively unexplored. Further questions exist as to how fungi interact cooperatively and noncooperatively with nonfungal constituents of the microbiome.

Fungal colonization of the term infant remains poorly characterized. Although it is known that fungi, such as Candida, are prevalent constituents of the vagina through which most infants are delivered, transmission to the newborn is not well documented, and assembly of additional environmental fungi into the microbiome has not been monitored in the otherwise healthy infant.

Although the microbiome of the healthy term infant remains poorly understood, more effort has been placed on understanding fungal colonization of preterm infants. Infants born 8 or more weeks before term and weighing ≤1500 g at birth are at significantly increased risk for invasive fungal disease, primarily with Candida species (spp.) these infants at risk of Candida colonization and infection.

Based on culture-dependent or genus/species-focused culture-independent methods of identification, the fungi of the oral cavity were previously believed to be few and relatively nondiverse. The genera Candida, Saccharomyces, Penicillium,Aspergillus, Scopulariopsis, and Genotrichum were among those previously reported.... In the oral samples from 20 participants, most had ∼15 fungal genera present...To put this level of diversity into context, prior studies have identified more than 50–100 bacterial genera in the healthy oral microbiome.

Of the oral fungal genera noted among each of the healthy subjects from the Ghannoum study (Ghannoum et al. 2010), Candida and Cladosporium were most common, present in 75% and 65% of participants, respectively. Fungal genera associated with local oral and invasive diseases, including Aspergillus,Cryptococcus, Fusarium, and Alternaria were also identified, indicating that these genera are present in the oral microbiome even during a state of health....The discovery of previously unidentified fungi is a reminder that the oral microbiome remains underexplored.

Although the bacterial constituents of the gut-associated microbiome have been intensely studied, the diversity and function of gut-associated fungi is understudied and lags far behind other aspects of microbiome studies.Only recently have larger studies specifically focused on the gut mycobiome been performed. Hoffmann et al. (2013).... from 98 healthy individuals without known gastrointestinal disease. In total, the researchers identified 66 fungal genera with 13 additional taxa for which a genus-level classification was not possible. An estimated 184 species were present in total. Eighty-nine percent of the samples had Saccharomyces present. Candida and Cladosporium were the second and third most prevalent, present in 57% and 42% of samples, respectively. The research was not able to definitively determine whether certain taxa were resident fungal microbota or transient as part of dietary intake.

Mutualism between fungi and humans is generally not well understood and has not been well studied. However, several examples related to the gut microbiome provide evidence of a beneficial relationship. S. boulardii, closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has been studied in controlled trials for the prevention and mitigation of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile...These studies show the potency of fungi to compete with pathogenic organisms, modify intestinal function, and attenuate inflammation, presumably because of an interaction with the intestinal microbiota....A recent retrospective data review suggested an inverse relationship between Candida and C. difficile, pointing to some common impact of yeast on the gut microbiome and the exclusion of C. difficle outgrowth and/or toxin production (Manian and Bryant 2013).

Humans have a lifelong interaction with complex microbial communities distributed across the body, which fundamentally contributes to the development and physiology of the macro-organism. Only recently has the diversity of fungi within the human microbiome begun to be determined, with early studies showing that, although relatively nonabundant, fungi are diverse within the microbiome as a whole. Although still in the early stage, studies suggest complex interactions between fungal and bacterial constituents of the microbiome.

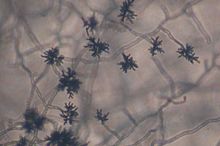

Microspcopic image of intestinal fungus. Credit: Iliyan Iliev

Microspcopic image of intestinal fungus. Credit: Iliyan Iliev

Every time you inhale, you suck in thousands of microbes. And depending on where you live, the microbes will vary. From Wired:

Every time you inhale, you suck in thousands of microbes. And depending on where you live, the microbes will vary. From Wired: This nice general summary of what scientists know about the microbial community within us was just published by a division of the NIH (National Institutes of Health). Very simple and basic. From the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS):

This nice general summary of what scientists know about the microbial community within us was just published by a division of the NIH (National Institutes of Health). Very simple and basic. From the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS): A

A