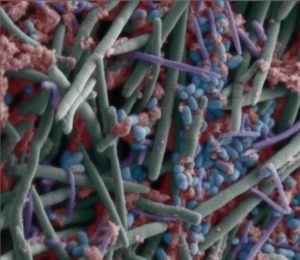

Something new and complex to think about. We humans have genes (about 20, 000), and then the microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi) within us have genes (between 2 million and 20 million) . And now it looks like some of their genes have slipped into our genes (horizontal gene transfer). An example: the genes that determine blood types (A, B, O) . Whew....Another totally new thing to think about in our evolutionary history. From Time:

You may be your germs: Microbe genes slipped into human DNA, study says

Evolutionary diagrams usually connect humans and monkeys with common primate ancestors, but now, scientists say there's a missing link that deserves a spot on that family tree -- our bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Though most of our genes come from primate ancestors, many of them slipped into our DNA from microbes living in our bodies, says British researcher Alastair Crisp. It's called horizontal gene transfer. Scientists have known of examples of this for a long time: Bacteria slip genes to each other, and it helps them evolve.

Some researchers have disputed that microbes have swapped genes with the cells of complex animals, such as humans. But a new study at the University of Cambridge indicates it has probably happened a lot. Humans may have as many as hundreds of so-called foreign genes they picked up from microbes.

"Surprisingly, far from being a rare occurrence, it appears that (horizontal gene transfer) has contributed to the evolution of many, perhaps all, animals and that the process is ongoing, meaning that we may need to re-evaluate how we think about evolution," Crisp said.

That may not surprise microbiologists.We humans and other complex animals are full of microbes, gajillions of them. People have so many that microbe cells living in our bodies outnumber our own vastly. A body has about 10 trillion human cells, says microbiologist Rob Knight. The microbe cells living inside of us number around 100 trillion. That's a ratio of 10 to one. The biggest collection is in our gut.

They're mostly helpful, and we we'd have a hard time living without them. Their genetic material dwarfs ours. The human genome adds up to 20,000 genes. The collective genomes of the many varieties of microbes in our bodies adds up to between 2 million and 20 million, Knight says.

In recent decades, scientists laid down genomes -- a detailed description of gene sequences -- for all kinds of species, including humans. The Cambridge researchers compared the genomes of various species of fruit flies, worms and primates, including humans.

They calculated similarities and differences between the genes across those species to look for ones that stuck out as not being part of a smooth evolutionary lineage, but instead probably popped in at some point. They found 128 formerly unidentified "foreign" genes in humans and confirmed 17 that had previously been reported. Most of them play a role in digestion. But the scientists also found that the gene that determines blood types -- A, B and O -- is "foreign." Some "foreign" genes that transferred in from microbes help our bodies' immune systems defend against microbial infections like bacteria and fungi.

Research is accumulating that the microbial exposure from a vaginal birth, breastfeeding, and pets in the first year of life are all good for a baby's developing immune system and the gut microbiome.

Research is accumulating that the microbial exposure from a vaginal birth, breastfeeding, and pets in the first year of life are all good for a baby's developing immune system and the gut microbiome. Gut bacteria in children varies among different Asian countries. A

Gut bacteria in children varies among different Asian countries. A  This research suggests that emulsifiers (which are added to most processed foods to aid texture and extend shelf life) can alter the

This research suggests that emulsifiers (which are added to most processed foods to aid texture and extend shelf life) can alter the Nice summary of cancer prevention advice. What it boils down to is that there is no magic bullet for cancer prevention (maybe the closest thing is to NOT smoke), but it's a lot of little things adding up (your lifestyle) that lowers the risk of cancer. From The Washington Post:

Nice summary of cancer prevention advice. What it boils down to is that there is no magic bullet for cancer prevention (maybe the closest thing is to NOT smoke), but it's a lot of little things adding up (your lifestyle) that lowers the risk of cancer. From The Washington Post: