The following article excerpts are from the talk "Food and Brain" about the best foods for the brain, at the annual 2015 meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA). This is in the new emerging field of food psychiatry, or how certain foods and diet influence the brain. The data is emerging that we can positively influence mental health through dietary interventions. For ex.: recent work reported that adults who followed the Mediterranean dietary pattern the closest over 4.4 years had a significantly reduced risk of developing depression (by 40% to 60%).

One key comment was: "Perhaps diet is the closest we've come to prevention in psychiatry." Some foods that are especially beneficial for the brain: seafood, greens, nuts, legumes (beans) and occasional dark chocolate. Use smaller amounts of meat (more as flavorings rather than just eating huge chunks of it) on top of a plant based diet. Also mentioned were the benefits of turmeric (because of the curcumin in it) and rosemary. And focus on improving the whole dietary pattern rather than just eating or not eating certain foods.

Note that BDNF is Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. This is a protein that acts on the brain, the nervous system, and it is very important for learning, memory, and higher thinking. So increasing BDNF levels is good. And remember, what's good for the brain is also good for the body and microbes - it's all intertwined. From Medscape:

Beans, Greens, and the Best Foods For the Brain

Dr Ramsey, in collaboration with the new International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry, is in the process of developing a standardized "brain food diet." "Food is a very effective and underutilized intervention in mental health," he started off. "We want to help our patients have more resilient brains by using whole foods...by helping get patients off of processed foods, off of white carbohydrates, and off of certain vegetable oils."

Though the field is in its infancy, food psychiatry is increasingly being embraced by clinicians and researchers, as a paper published earlier this year in the Lancet Psychiatry attests. "Although the determinants of mental health are complex," the authors wrote, "the emerging and compelling evidence for nutrition as a crucial factor in the high prevalence and incidence of mental disorders suggests that diet is as important to psychiatry as it is to cardiology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology." ..."The data are very promising that we can positively influence mental health through dietary interventions," commented Dr Ramsey.

"Hominid diets have changed drastically through millions of years of evolution.,,,But only in the past 100 years has our diet drastically switched from a whole foods diet to one that is more processed and high in refined carbohydrates; that includes more vegetable fats rather than meat fats; and preservatives, emulsifiers, and other additives, which appear to have contributed to a decline in our collective health.

Early humans evolved in the African Rift Valley, which is near a seacoast. It's possible that whatever evolutionary spark occurred that made us human occurred here, in part due to reliable access to seafood—oysters in particular—which glutted our brains with omega-3 fatty acids and cholesterol (our brains are composed of 60% fat). Oysters and other mollusks are also very high in nutrients, including B12, which is commonly deficient in people consuming vegan or vegetarian diets and is necessary for myelin and neurotransmitter function.

A number of studies have linked the Mediterranean diet (high in fish oils, nuts, and grains and including maybe a little red wine) with advantageous effects on neurologic and mental health. Dr Deans cited recent work reporting that adults who followed the Mediterranean dietary pattern the closest over 4.4 years had a significantly reduced risk of developing depression (40%-60%)....When taken together, most of these dietary pattern studies, which have been conducted all over the world, consistently show that traditional, pre-processed diets are the healthiest, including for the brain. ..."Eat the rainbow," he says, given that bold, bright colors in nature tend to signify valuable vitamins and phytonutrients (the reds, purples, and greens in particular).

Seafood: Seafood is packed with brain-healthy omega-3 fatty acids. These healthy fats are also abundant in plants like chia and flax, but plant-based sources aren't as efficiently converted to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), an important structural component of neuronal membranes. DHA also influences the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which can benefit people who have mood and anxiety disorders. Bivalves like mussels, oysters, and clams are the top source of vitamin B12 as well as zinc: Six oysters (only about 10 calories each) provide 240% of our recommended daily B12 intake and 500% of our recommended zinc intake! Seafood is also a leading dietary source of vitamin D (we don't get it all from the sun) as well as iodine and chromium. Although many people worry about mercury in fish, Dr Ramsey provided an easy way around the concern: Eat small fish like sardines, anchovies, and herring, which typically don't accumulate toxic levels.

Leafy greens: A great base for a brain-food diet, leafy greens are a good source of fiber, folate (derived from the wordfoliage), magnesium, and vitamin K. Perhaps surprising, kale, mustard greens, and bok choy provide the most absorbable form of calcium on the planet, more so than milk. Greens also provide flavanols and carotenoids that have beneficial epigenetic influences (eg, including upping hepatic toxin processing).

Nuts:... Nuts are packed with healthy monounsaturated fats. They help keep us full and also aid in absorbing fat-soluble nutrients. Nuts also provide fiber as well as minerals like manganese and selenium. A serving of 22 almonds (just 162 calories) contains 33% of our recommended vitamin E, plenty of protein, and minerals, including iron. One study from 2013 found that the Mediterranean diet augmented with nuts is associated with significantly higher BDNF levels in patients with depression.

Legumes: Dr Ramsey is pro-meat, but he acknowledges that many people are eating far too much and the wrong types of meat, and that nuts and legumes are a great alternative source of protein and nutrients...Some data suggest that vegan and vegetarian diets are associated with improved mood. But as previously mentioned, these dietary patterns can result in B12 deficiency, which has been associated with brain atrophy and developmental delay. Hence, supplementation is important in this population. Vegetarianism has also been linked with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, as well as increased healthcare utilization and worse quality of life. These negative associations also could be due to the fact that it's harder to absorb nutrients like zinc, iron, and certain omega-3s from plants.

"The notion that the vegan diet is the healthiest diet on the planet is probably incorrect," said Dr Ramsey, before explaining that he just feels that we should approach meat in our diets differently....We want to help patients use beef and seafood more as flavorings on top of a plant-based diet." A modest amount of meat in the diet has its benefits, including nutrient availability: Hemoglobin-derived iron is up to 40% more absorbable than plant-based iron. Unlike most plants, meat provides all of the amino acids necessary for protein synthesis. Dr Ramsey emphasized the importance of seeking out leaner, grass-fed meats if one has the means.

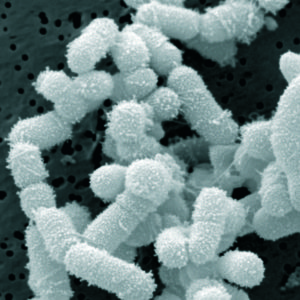

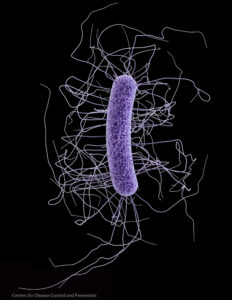

The understanding of how microbiota contribute to our mental and medical well-being is rapidly advancing....One of the most powerful interventions to alter our microbiome is diet. Research shows that stressed mice experienced changes in the gastrointestinal microbiota, reflecting the gut-brain relationship. There are 260 million neurons connecting the gut and the brain; furthermore, many commensal gut bacteria make neurotransmitters and communicate with the brain via the vagus nerve....Although the science of probiotic therapies is relatively young, it's clear that these commensal organisms co-evolved with us and are adapted to our diet.

Finally, to close out the session, Dr Ramsey returned to the stage and asked, "So, can you eat to build a better brain? We think that you can if you focus on dietary patterns and not a single food here or there." He also reminded the audience to help their patients identify and increase their consumption of nutrient-dense foods and to "eat the rainbow,"..."I don't know of anything else that can potentially decrease the risk of depression in a population by 40%," he concluded. "Perhaps diet is the closest we've come to prevention in psychiatry."

...Evidence suggests that curcumin, an ingredient in turmeric, increases BDNF. Other research has found that populations that eat more curry have a decreased risk for dementia, while rosemary extract may help prevent cognitive impairment. "Many spices seem to have healing properties," Dr Ramsey commented.

Although the "Food and the Brain" session at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting focused on what to eat in the interest of brain health, intermittent fasting might also be beneficial for the brain. In addition to helping maintain a healthy weight, fasting induces ketosis. Ketone metabolism has been shown to be beneficial for the brain and improve cognition in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. Keep in mind that fasting can come with risks for some people, particularly diabetics, and should be discussed with a healthcare provider.

Yes, even healthy newborns have a diversity of viruses in the gut - this is their virome (community of viruses), and it undergoes changes over time. In fact, the entire infant microbiome (community of microbes) is highly dynamic and the composition of bacteria, viruses and bacteriophages changes with age. One interesting finding is that initially newborn babies have a lot of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria), but that these decline over the first two years of age. From Medical Xpress:

Yes, even healthy newborns have a diversity of viruses in the gut - this is their virome (community of viruses), and it undergoes changes over time. In fact, the entire infant microbiome (community of microbes) is highly dynamic and the composition of bacteria, viruses and bacteriophages changes with age. One interesting finding is that initially newborn babies have a lot of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria), but that these decline over the first two years of age. From Medical Xpress:

[UPDATE: I added an Oct. 2018 update to the post

[UPDATE: I added an Oct. 2018 update to the post  Another article from results of the crowdsourced study in which household dust samples were sent to researchers at the University of Colorado from approximately 1200 homes across the United States. Some findings after the dust was analyzed: differences were found in the dust of households that were occupied by more males than females and vice versa, indoor fungi mainly comes from the outside and varies with the geographical location of the house, bacteria is determined by the

Another article from results of the crowdsourced study in which household dust samples were sent to researchers at the University of Colorado from approximately 1200 homes across the United States. Some findings after the dust was analyzed: differences were found in the dust of households that were occupied by more males than females and vice versa, indoor fungi mainly comes from the outside and varies with the geographical location of the house, bacteria is determined by the  This article discusses the fungi living on our skin. Recent research (using state of the art genetic analysis) has found that healthy people have lots of diversity in fungi living on their skin. Certain areas seem to have the greatest populations of fungi:

This article discusses the fungi living on our skin. Recent research (using state of the art genetic analysis) has found that healthy people have lots of diversity in fungi living on their skin. Certain areas seem to have the greatest populations of fungi:  More research that supports that both more variety (diversity) of microbes and the actual mix of types of microbes are involved in a healthy

More research that supports that both more variety (diversity) of microbes and the actual mix of types of microbes are involved in a healthy  There has been much discussion recently about breastfeeding - why is it so important? Is it really better than formula? The answer is: YES, breastfeeding is the BEST food for the baby, and for a number of reasons. Not only is it nature's perfect food for the baby, but it also helps the development of the baby's microbiome or microbiota (the community of microbes that live within and on humans).

There has been much discussion recently about breastfeeding - why is it so important? Is it really better than formula? The answer is: YES, breastfeeding is the BEST food for the baby, and for a number of reasons. Not only is it nature's perfect food for the baby, but it also helps the development of the baby's microbiome or microbiota (the community of microbes that live within and on humans).

Recently several good books have been published about the community of microbes within us - our microbiota or microbiome. Originally I mainly saw the term human microbiome used everywhere. It referred to all the organisms living within and on us that are identified by their

Recently several good books have been published about the community of microbes within us - our microbiota or microbiome. Originally I mainly saw the term human microbiome used everywhere. It referred to all the organisms living within and on us that are identified by their