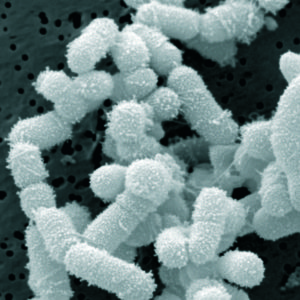

New discoveries of what is going on in our intestines, plus a new vocabulary to understand it all. Yes, it all is amazingly complex. Bottom line: we have complex communities (bacteria, bacterial viruses or bacteriophages, etc.) living and interacting in our intestines. And only with state-of-the-art genetic analysis (DNA sequencing) can we even "see" what is going on. I highlighted really important items in bold type. From Medical Xpress:

Researchers uncover new knowledge about our intestines

Researchers from Technical University of Denmark Systems Biology have mapped 500 previously unknown microorganisms in human intestinal flora as well as 800 also unknown bacterial viruses (also called bacteriophages) which attack intestinal bacteria.

"Using our method, researchers are now able to identify and collect genomes from previously unknown microorganisms in even highly complex microbial societies. This provides us with an overview we have not enjoyed previously," says Professor Søren Brunak who has co-headed the study together with Associate Professor Henrik Bjørn Nielsen.

So far, 200-300 intestinal bacterial species have been mapped. Now, the number will be more than doubled, which could significantly improve our understanding and treatment of a large number of diseases such as type 2 diabetes, asthma and obesity.

The two researchers have also studied the mutual relations between bacteria and viruses. Previously, bacteria were studied individually in the laboratory, but researchers are becoming increasingly aware that in order to understand the intestinal flora, you need to look at the interaction between the many different bacteria found.

And when we know the intestinal bacteria interactions, we can potentially develop a more selective way to treat a number of diseases. "Ideally we will be able to add or remove specific bacteria in the intestinal system and in this way induce a healthier intestinal flora," says Søren Brunak.

From Science Daily:

Revolutionary approach to studying intestinal microbiota

Analyzing the global genome, or the metagenome of the intestinal microbiota, has taken a turn, thanks to a new approach to study developed by an international research team. This method markedly simplifies microbiome analysis and renders it more powerful. The scientists have thus been able to sequence and assemble the complete genome of 238 intestinal bacteria, 75% of which were previously unknown.

Research carried out in recent years on the intestinal microbiota has completely overturned our vision of the human gut ecosystem. Indeed, from "simple digesters" of food, these bacteria have become major factors in understanding certain diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, or Crohn's disease. Important and direct links have also been demonstrated between these bacteria and the immune system, as well as with the brain. It is estimated that 100,000 billion bacteria populate the gut of each individual (or 10 to 100 times more than the number of cells in the human body), and their diversity is considerable, estimated to around a thousand different bacterial species in the intestinal human metagenome. However, because only 15% of these bacteria were previously isolated and characterized by genome sequencing, an immense number of the microbial genes previously identified still need to be assigned to a given species.

An analysis of 396 stool samples from Danish and Spanish individuals allowed the researchers to cluster these millions of genes into 7381 co-abundance groups of genes. Approximately 10% of these groups (741) corresponded to bacterial species referred to as metagenomic species (MGS); the others corresponded to bacterial viruses (848 bacteriophages were discovered), plasmids (circular, bacterial DNA fragments) or genes which protected bacteria from viral attack (known as CRISPR sequences). 85% of these MGS constituted unknown bacteria species (or ~630 species).

Using this new approach, the researchers succeeded in reconstituting the complete genome of 238 of these unknown species, without prior culture of these bacteria. Living without oxygen, in an environment that is difficult to characterise and reproduce, most of these gut bacteria cannot be cultured in the laboratory.

The authors also demonstrated more than 800 dependent relationships within the 7381 gene co-abundance groups; this was the case, for example, of phages which require the presence of a bacterium to survive. These dependent relationships thus enable a clearer understanding of the survival mechanisms of a micro-organism in its ecosystem.

Several people have recently written to me about kimchi and asked why I originally chose vegan kimchi over kimchi containing a seafood ingredient (typically fish or shrimp sauce) for sinusitis treatment. I have also been asked whether vegan kimchi has enough Lactobacillus sakei bacteria in it as compared to kimchi made with a seafood seasoning. (see Sinusitis Treatment Summary page and/or Sinusitis posts for in-depth discussions of Lactobacillus sakei in successful sinusitis treatment).

Several people have recently written to me about kimchi and asked why I originally chose vegan kimchi over kimchi containing a seafood ingredient (typically fish or shrimp sauce) for sinusitis treatment. I have also been asked whether vegan kimchi has enough Lactobacillus sakei bacteria in it as compared to kimchi made with a seafood seasoning. (see Sinusitis Treatment Summary page and/or Sinusitis posts for in-depth discussions of Lactobacillus sakei in successful sinusitis treatment).

For those who missed it. An amusing and informative personal story (Julia Scott) about trying to cultivate a healthy skin biome. Well worth reading. Excerpts from the May 22, 2014 NY Times:

For those who missed it. An amusing and informative personal story (Julia Scott) about trying to cultivate a healthy skin biome. Well worth reading. Excerpts from the May 22, 2014 NY Times:

A big benefit to exercising - more microbial diversity, which means a healthier gut microbiome, which means better health. From Medscape:

A big benefit to exercising - more microbial diversity, which means a healthier gut microbiome, which means better health. From Medscape: Yesterday I read and reread a very interesting journal review paper from Sept. 2013 that discussed recent studies about probiotics and treatment of respiratory ailments, including sinusitis. Two of the authors are those from the

Yesterday I read and reread a very interesting journal review paper from Sept. 2013 that discussed recent studies about probiotics and treatment of respiratory ailments, including sinusitis. Two of the authors are those from the